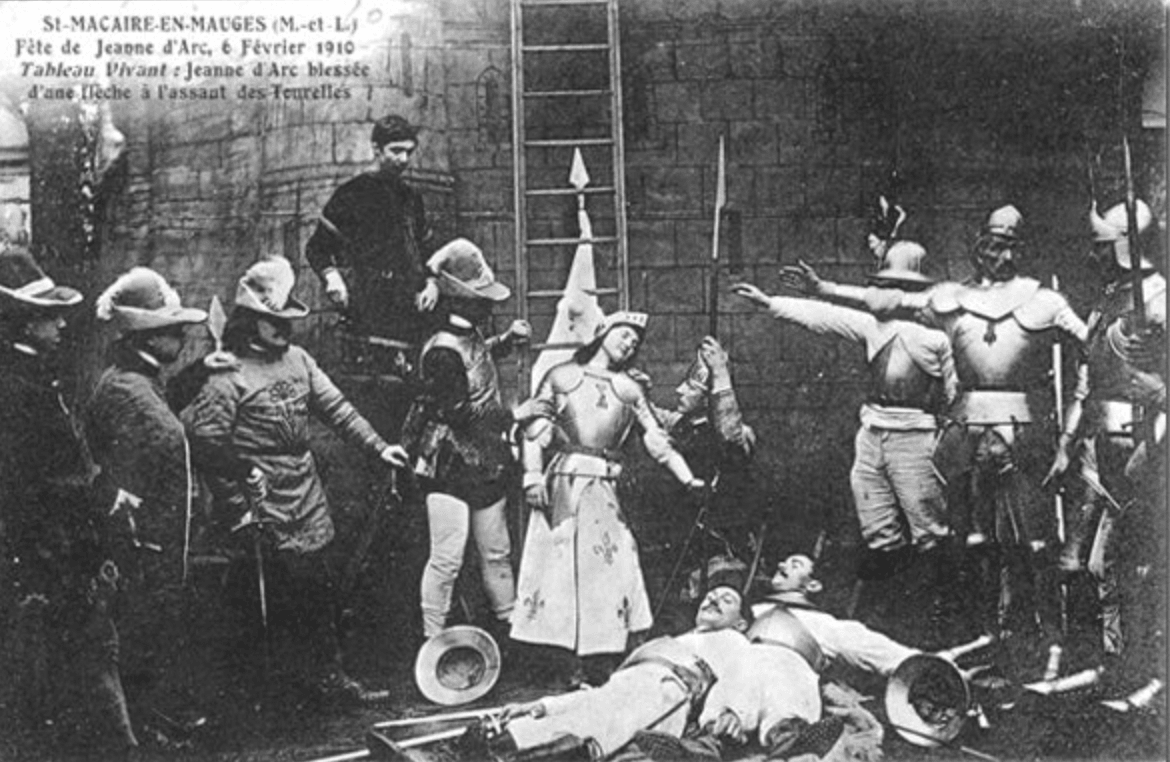

Tableaux Vivants

Tableau vivant (plural: tableaux vivants) is French for "living picture." The term describes a striking group of suitably costumed actors or artist's models, carefully posed and often theatrically lit. Throughout the duration of the display, the people shown do not speak or move. The phrase and the practice probably began in medieval liturgical dramas such as the Golden Mass, where on special occasions a Mass was punctuated by short dramatic scenes and tableaux. They were a major feature of festivities for royal weddings, coronations and Royal entries into cities. Often the actors imitated statues, much in the way of modern street entertainers, but in larger groups, mounted on elaborate temporary stands along the path of the main procession.*

Tableau vivant (plural: tableaux vivants) is French for "living picture." The term describes a striking group of suitably costumed actors or artist's models, carefully posed and often theatrically lit. Throughout the duration of the display, the people shown do not speak or move. The phrase and the practice probably began in medieval liturgical dramas such as the Golden Mass, where on special occasions a Mass was punctuated by short dramatic scenes and tableaux. They were a major feature of festivities for royal weddings, coronations and Royal entries into cities. Often the actors imitated statues, much in the way of modern street entertainers, but in larger groups, mounted on elaborate temporary stands along the path of the main procession.*

Parlour Tableaux were a particular kind of social entertainment that reached its prime in the 19th century. Consisting of people, usually wealthy guests at a party, dressing up and posing as a painting or etching of their choice, they play pivotal roles in several novels of the day, including Jane Eyre and The House of Mirth. Piquant and lustrous, it more or less died out as a result of the boom of the entertainment business in the 20th century, and the birth of cinematography.**  Tableaux Vivants evolved from educational and artistic performances to parlour games and charades and then, during the Victorian era, they took a darker turn with the introduction of "poses plastiques"-- scantily clad actresses recreating famous statues. The following instructions for playing Tableaux Vivants are from Cassell's Book of Amusements, Card Games and Fireside Fun, 1881.

Tableaux Vivants evolved from educational and artistic performances to parlour games and charades and then, during the Victorian era, they took a darker turn with the introduction of "poses plastiques"-- scantily clad actresses recreating famous statues. The following instructions for playing Tableaux Vivants are from Cassell's Book of Amusements, Card Games and Fireside Fun, 1881.

Tableaux Vivants In the estimation of some people Tableaux Vivants possess even greater attractions tha Charades, simply for the reason that in their representation no conversational power is required. The performers have to remain perfectly silent, looking rather than speaking their thoughts; proclaiming by the attitude in which they place themselves, and by the expression of their countenances, the tale they have to tell. To others, however, this silent acting is infinitely more difficult than the incessant talk and gesticulation required in charade actors. Naturally active, and gifted with a ready flow of words, the ordeal of having to remain motionless and silent, for even three or four minutes, would be equal to the infliction upon themselves of absolute pain. Still we must not be led to think that individuals devoid of character are the most eligible to take part in Tableaux Vivants; no greater mistake could be made.

The affair is sure ot be a failure unless the actors not only have the perfect command of feeling, but are able also to enter completely into the spirit of the subject they attempt to depict. It would be useless to expect a lady to personate Lad Macbeth who had never read the play, and who, therefore, knew nothing of the motives which prompted that ambitious woman in her guilty career. In order to give effect to the scene the subject must be familiar and thoroughly understood by the actors. There is seldom any difficulty in the selection of subjects. Historical remembrances are always acceptable, and can be made to speak very plainly for themselves, while fictitious and poetical scenes may be rendered simply charming. Speaking from experience, one of the prettiest Tableaux Vivants we ever saw was one taken from Shakespeare's "Winter's Tale." As soon as the curtain was drawn aside, Hermione was seen on a raised pedestal, so lifeless and calm she might well have been mistaken for marble. Before her was standing Leontes, and old man, with his daughter, Perdita, hanging on his arm, both evidently struck dumb with amazement at the likeness of the statue to her who for so many years they had believed to be dead; while Camillo, Glorizel, and Polienes, aslo stood gazing in wonder. The good Paulina, dresses as a Sicililan matron, stood behind the Statute, or rather on one side, as the exhibitor of it. Presently were heard strains of gentle music, when the Statue stepped gracefully from her elevation, gave her hand to Leontes, and was embraced by him. The curtain here was drawn forward again, hiding from our sight a picture what ever since has been printed indelibly upon our memory. For comic tableaux scenes from fairyland or nursery rhymes, would answer the purpose admirably.

Some young lady with long hair might be made to be seen kneeling as Fatima, before her cruel, hard-hearted husband, Blue Beard; he with her hair in one hand, and a drawn sword in the other, just about to commit the horrid deed; the sister meantime straining her eyes out of the window, to catch sight of her brothers, who she knows are coming with all speed to the rescue. As to dressing the scenery, they are matters that must be lef to the taste and fancy of the managers of the concern, who will soon discover that the success of the Tableaux, even more than Charades, depends very greatly upon dress and surroundings. Charades speak for themselves, but Tableaux are so soon over, that unless the actors assume somewhat of the dress of the characters they attempt to personate, the audience will not readily guess the subject chosen. There is little doubt that with both Charade performers, and with those who take part in Tableaux Vivants, the assumed dress gives and air of importance to the proceedings which would not otherwise exist, and acts like a kind of inspiration (upon young people especially), making them perhaps more thoroughly lose their own personality in trying to be someone else.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.