The Young Man's Guide to Choosing a Partner

The Young Man's Guide

'Mr Collins, you must marry. A clergyman like you must marry. -- Chuse properly, chuse a gentlewoman for my sake; and for your own, let her be an active, useful sort of person, not brought up high, but able to make a small income go a good way. This is my advice.Find such a woman as soon as you can, bring her to Hunsford, and I will visit her.' Lady Catherine de Bourgh, Pride and PrejudiceThe following chapter is abridged from The Young Man's Guide by William A. Alcott, printed in 1835. While this was not published during Jane Austen's lifetime, many of these ideals were in place long before the Regency period, though some appear almost ludicrous to our modern sensibilities.

Female Qualifications for Marriage

1. Moral Excellence

The highest as well as noblest trait in female character, is love to God. Christianity is based on the most abundant evidence, of a character wholly unquestionable. But this I do and will say, that to be consistent, young men of loose principled ought not to rail at females for their piety, and then whenever they seek for a constant friend, one whom they can love, -- for they never really love the abandoned, -- always prefer, other things being equal, the society of the pious and the virtuous.

2. Common Sense

2. Common Sense

Next on the list of particular qualifications in a female, for matrimonial life, I place common sense. In the view of some, it ought to precede moral excellence. By common sense, as used in this place, I mean the faculty by means of which we see things as they really are. It implies judgment and discrimination, and a proper sense of propriety in regard to the common concerns of life. It leads us to form judicious plans of action, and to be governed by our circumstances in such a way as will be generally approved. It is the exercise of reason, uninfluenced by passion or prejudice. To man, it is nearly what instinct is to brutes. It is very different from genius or talent, as they are commonly defined; but much better than either. It never blazes forth with the splendor of noon, but shines with a constant and useful light. To the housewife -- but, above all, to the mother, -- it is indispensable.

3. A Desire for Improvement

3. A Desire for Improvement

Whatever other recommendations a lady may possess, she should have an inextinguishable thirst for improvement. No sensible person can be truly happy in the world, without this; much less qualified to make others happy. But the genuine spirit of improvement, whereever it exists, atones for the absence of many qualities which would otherwise be indispensable: in this respect resembling that 'charity' which covers 'a multitude of sins.' Without it, almost everything would be of little consequence, -- with it, everything else is rendered doubly valuable. With the fond, the ardent, the never failing desire to improve, physically, intellectually, and morally, there are few females who may not make tolerable companions for a man of sense; -- without it, though a young lady were beautiful and otherwise lovely beyond comparison, wealthy as the Indies, surrounded by thousands of the most worthy friends, and even talented, let him beware! Better remain in celibacy a thousand years (could life last so long) great as the evil may be, than form a union with such an object. He should pity, and seek her reformation, if not beyond the bounds of possibility; but love her he should not! The penalty will be absolutely insupportable.

4. A Fondness for Children

Few traits of female character are more important than this. Yet there is much reason to believe that, even in comtemplating an engagement that is expected to last for life, it is almost universally overlooked. Without it, though a woman should possess every accomplishment of person, mind and manners, she would be poor indeed; and would probably render those around her miserable. I speak now generally. There may be exceptions to this, as to other general rules. A dislike of children, even in men, is an unfavorable omen; in woman it is insupportable; for it is grossly unnatural.

To a susceptible, intelligent, virtuous mind, I can scarcely conceive of a worse situation in this world or any other, than to be chained for life to a person who hates children. You can purchase, if you have the pecuniary means, almost every things but maternal love.  This no gold can buy. Wo to the female who is doomed to drag out a miserable existence with a husband who 'can't bear children;' but thrice miserable is the doom of him who has a wife and a family of children, but whose children have no mother! These remarks are made, not in the belief that they will benefit those who are already blinded by fancy or passion, but with the hope that some more fortunate reader may reflect on the probable chances of happiness or misery, and pause before he leaps into the vortex of matrimonial discord. No home can ever be a happy one to any of its inmates, where there is no maternal love, nor any desire for mental or moral improvement. But where these exist, in any considerable degree, and the original attachment was founded on correct principles, there is always hope of brighter days, even though clouds at present obscure the horizon. No woman who loves her husband, and desires to make continual improvement, will long consent to render those around her unhappy.

This no gold can buy. Wo to the female who is doomed to drag out a miserable existence with a husband who 'can't bear children;' but thrice miserable is the doom of him who has a wife and a family of children, but whose children have no mother! These remarks are made, not in the belief that they will benefit those who are already blinded by fancy or passion, but with the hope that some more fortunate reader may reflect on the probable chances of happiness or misery, and pause before he leaps into the vortex of matrimonial discord. No home can ever be a happy one to any of its inmates, where there is no maternal love, nor any desire for mental or moral improvement. But where these exist, in any considerable degree, and the original attachment was founded on correct principles, there is always hope of brighter days, even though clouds at present obscure the horizon. No woman who loves her husband, and desires to make continual improvement, will long consent to render those around her unhappy.

5. Love of Domestic Concerns

Without the knowledge and the love of domestic concerns, even the wife of a peer, is but a poor affair. It was the fashion, in former times, for ladies to understand a great deal about these things. and it would be very hard to make me believe that it did not tend to promote the interests and honor of their husbands. The concerns of a great family never can be well managed, if left wholly to hirelings; and there are many parts of these affairs in which it would be unseemly for husbands to meddle. Surely, no lady can be to high in rand to make it proper for her to be well acquainted with the character and general demeanor of all the female servants. To receive and give character is too much to be left to a servant, however good, whose service has been ever so long, or acceptable. It is cold comfort for a man, to marry a girl, who has been brought up only to 'play music;' to draw, to sing, to waste paper, pen and ink in writing long and half romantic letters, and to see shows, and plays, and read novels. Lovers may live on a very aerial diet, but husbands stand in need of something more solid; and young women may take my word for it, that a constantly clean table, well cooked victuals, a house in order, and a cheerful fire, will do more towards preserving a husband's heart, than all the 'accomplishments' taught in all the 'establishments' in the world without them.6. Sobriety

Surely no reasonable young man will expect sobriety in a companion, when he does not possess this qualification himself. But by sobriety, I do not mean a habit which is opposed to intoxication, for if that be hateful in a man, what must it be in a woman? Besides, it does seem to me that no young man, with his eyes open, and his other senses perfect, needs any caution on that point. Drunkenness, downright drunkenness, is usually as incompaticble with purity, as it is with decency.  Much is sometimes said in favor of a little wine or other fermented liquors, especially at dinner. No young lady, in health, needs any of these stimulants. Wine, or ale, or cider, at dinner! I would as soon take a companion from the streets, as one who must habitually have her glass or two of wine at dinner. And this is not a opinion formed prematurely or hastily. But by the word sobriety in a young woman, I mean a great deal more than even a rigid abstinence from a love of drink, which I do not believe to exist to any considerable degree, in this country, even in the least refined parts of it. I mean a great deal more than this; I mean sobriety of conduct. The word sober and its derivatives mean steadiness, seriousness, carefulness, scrupulous propriety of conduct. Now this kind of sobriety is of great importance in the person with whom we are to live constantly. Skipping, romping, rattling girls are very amusing where all consequences are out of the question, and they may, perhaps, ultimately become sober. But while you have no certainty of this, there is a presumptive argument on the other side. To be sure, when girls are mere children, they are expected to play and romp like children. But when they are arrived at an age which turns their thoughts towards a situation for life; when they begin to think of having the command of a house, however small or poor, it is time for them to cast away, not the cheerfulness or the simplicity, but the levity of the child.

Much is sometimes said in favor of a little wine or other fermented liquors, especially at dinner. No young lady, in health, needs any of these stimulants. Wine, or ale, or cider, at dinner! I would as soon take a companion from the streets, as one who must habitually have her glass or two of wine at dinner. And this is not a opinion formed prematurely or hastily. But by the word sobriety in a young woman, I mean a great deal more than even a rigid abstinence from a love of drink, which I do not believe to exist to any considerable degree, in this country, even in the least refined parts of it. I mean a great deal more than this; I mean sobriety of conduct. The word sober and its derivatives mean steadiness, seriousness, carefulness, scrupulous propriety of conduct. Now this kind of sobriety is of great importance in the person with whom we are to live constantly. Skipping, romping, rattling girls are very amusing where all consequences are out of the question, and they may, perhaps, ultimately become sober. But while you have no certainty of this, there is a presumptive argument on the other side. To be sure, when girls are mere children, they are expected to play and romp like children. But when they are arrived at an age which turns their thoughts towards a situation for life; when they begin to think of having the command of a house, however small or poor, it is time for them to cast away, not the cheerfulness or the simplicity, but the levity of the child.

7. Industry

Let not the individual whose eye catches the word industry, at the beginning of this division of my subject, condemn me as degrading females to the condition of mere wheels in a machine for money-making; for I mean no such thing. There is nothing more abhorrent to the soul of a sensible man than female avarice. The 'spirit of a man' may sustain him, while he sees avaricious and miserly individuals among his own sex, though the sight is painful enough, even here; but a female miser, 'who can bear?' Still if woman is intended to be a 'help meet,' for the other sex, I know of no reason why she should not be so in physical concerns, as well as mental and moral. I know not by what rule it is that many resolve to remain for ever in celibacy, unless they believe their companions can 'support' them, without labor. I have sometimes even doubted whether any person who makes these declarations can be sincere. Yet when I hear people, of both sexes, speak of poverty as a greater calamity than death, I am led to think that this dread of poverty does really exist among both sexes. And there are reasons for believing that some females, bred in fashionable life, look forward to matrimony as a state, of such entire exemption from care and labor, and of such uninterrupted ease, that they would prefer celibacy and even death to those duties which scripture, and reason, and common sense, appear to me to enjoin.  Another mark of industry is, a quick step, and a somewhat heavy tread, showing that the foot comes down with a hearty good will. If the body lean a little forward, and the eyes keep steadily in the same direction, while the feet are going, so much the better, for these discover earnestness to arrive at the intended point. I do not like, and I never like, your sauntering, soft-stepping girls, who move as if they were perfectly indifferent as to the result. And, as the the love part of the story, who ever expects ardent and lasting affection from one of these sauntering girls, will, when too late, find his mistake. The character is much the same throughout; and probably no man ever yet saw a sauntering girl, who did not, when married, make an indifferent wife, and a cold-hearted mother; cared very little for, either by husband or children; and, of course, having no store of those blessings which are the natural resources to apply to in sickness and in old age

Another mark of industry is, a quick step, and a somewhat heavy tread, showing that the foot comes down with a hearty good will. If the body lean a little forward, and the eyes keep steadily in the same direction, while the feet are going, so much the better, for these discover earnestness to arrive at the intended point. I do not like, and I never like, your sauntering, soft-stepping girls, who move as if they were perfectly indifferent as to the result. And, as the the love part of the story, who ever expects ardent and lasting affection from one of these sauntering girls, will, when too late, find his mistake. The character is much the same throughout; and probably no man ever yet saw a sauntering girl, who did not, when married, make an indifferent wife, and a cold-hearted mother; cared very little for, either by husband or children; and, of course, having no store of those blessings which are the natural resources to apply to in sickness and in old age

8. Early Rising

Early rising is another mark of industry; and though, in the higher stations of life, it may be of no importance in a mere pecuniary point of view, it is, even there, of importance in other respects; for it is rather difficult to keep love alive towards a woman who never sees the dew, never beholds the rising sun, and who constantly comes directly from a reeking bed to the breakfast table, and there chews, without appetite, the choicest morsels of human food. A man might, perhaps, endure this for a month or two, without being disgusted; but not much longer.9. Frugality

This means the contrary of extravagance. it does not mean stinginess; it does not mean pinching; but it means an abstaining from all unnecessary expenditure, and all unnecessary use of goods of any and of every sort. It is a quality of great importance, whether the rank of life be high of low. Some people are, indeed, so rich, they have such an over-abundance of money and goods, that how to get rid of them would, to a spectator, seem to be their only difficulty. How many individuals of fine estates, have been ruined and degraded by the extravagance of their wives! More frequently by their own extravagance, perhaps; but, in numerous instances, by that of those whose duty it is to assist in upholding their stations by husbanding their fortunes. If this be the case amongst the opulent, who have estates to draw upon, what must be the consequences of a want of frugality in the middle and lower ranks of life? Here it must be fatal, and especially among that description of persons whose wives have, in many cases, the receiving as well as the spending of money. In such a a case, there wants nothing but extravagance in the wife to make ruin as inevitable as the arrival of old age. To marry a girl of this disposition is really self-destruction. You never can have either property or peace. Earn her a horse to ride, she will want a gig: earn the gig, she will want a chariot: get her that, she will long for a coach and four: and from stage to stage, she will torment you to the end of her or your days; for, still there will be somebody with a finer equipage that you can give her; and, as long as this is the case, you will never have rest. Reason would tell her, that she must stop at some point short of that; and taht, therefore, all expenses in the rivalship are so much thrown away. But, reason and broaches and bracelets seldom go in company. The girl who has not the sense to perceive that her person is disfigured and not beautified by parcels of brass and tin, or even gold and silver, as well to regret, if she dare not oppose the tyranny of absurd fashions, is not entitled to a full measure of confidence of any individual.

10. Personal Neatness

10. Personal Neatness

There never yet was, and there never will be sincere and ardent love, of long duration, where personal neatness is wholly neglected. I do not say that there are not those who would live peaceably and even contentedly in these circumstances. But what I contend for is this: that there never can exist, for any length of time, ardent affection, in any man towards a woman who neglects neatness, either in her person, or in her house affairs. Men may be careless as to their own persons; they may, from the nature of their business, or from their want of time to adhere to neatness in dress, be slovenly in their own dress and habits; but, they do not relish this in their wives, who must still have charms; and charms and neglect of the person seldom go together. I do not, of course, approve of it even in men. We may, indeed, lay it down as a rule of almost universal application, that supposing all other things to be equal, he who is most guilty of personal neglect; will be the most ignorant and the most vicious. Why there should be, universally, a connection between slovenliness, ignorance, and vice, is a question I have no room in this work to discuss.

The indications of female neatness are, first, a clean skin. The hands and face will usually be clean, to be sure, if there be soap and water within reach; but if on observing other parts of the head besides the face, you make discoveries indicating a different character, the sooner you cease your visits the better. I hope, now, that no young woman who may chance to see this book, will be offended at this, and think me too severe on her sex. I am only telling that which all men think; and, it is a decided advantage to them to be fully informed of our thoughts on the subject. If any one, who reads this, shall find, upon self- examination, that she is defective in this respect, let her take the hint, and correct this defect. How much do women lose by inattention to these matters! Men, in general, say nothing about it to their wives, but they think about it; they envy their more lucky neighbors, and in numerous cases, consequences the most serious arise from this apparently trifling cause. Beauty is valuable; it is one of the ties, and strong one too; but it cannot last to old age; whereas the charm of cleanliness never ends but with life itself. It has been said that the sweetest flowers, when they really become putrid, are the most offensive. So the most beautiful woman, if found with an uncleansed skin, is, in my estimation, the most disagreeable.

11. A Good Temper

This is a very difficult thing to ascertain beforehand. Smiles are cheap; they are easily put on for the occasion; and, besides, the frowns are, according to the lover's whim, interpreted into the contrary. By 'good temper,' I do not mean an easy temper, a serenity which nothing disturbs; for that is a mark of laziness. Sullenness, if you be not too blind to perceive it, is a temper to be avoided by all means. A sullen man is bad enough; what, then, must a sullen woman, and that woman a wife; a constant inmate, a companion day and night! Only think of the delight of setting at the same table, and occupying the same chamber, for a week, without exchanging a word for all the while! Very bad to be scolding for such a length of time; but this is far better than 'the sulks.' Querulousness is a great fault.

This is a very difficult thing to ascertain beforehand. Smiles are cheap; they are easily put on for the occasion; and, besides, the frowns are, according to the lover's whim, interpreted into the contrary. By 'good temper,' I do not mean an easy temper, a serenity which nothing disturbs; for that is a mark of laziness. Sullenness, if you be not too blind to perceive it, is a temper to be avoided by all means. A sullen man is bad enough; what, then, must a sullen woman, and that woman a wife; a constant inmate, a companion day and night! Only think of the delight of setting at the same table, and occupying the same chamber, for a week, without exchanging a word for all the while! Very bad to be scolding for such a length of time; but this is far better than 'the sulks.' Querulousness is a great fault.

No man, and, especially, no woman, likes to hear a continual plaintiveness. That she complain, and roundly complain, of your want of punctuality, of your coolness, of your neglect, of your liking the company of others: these are all well, more especially as they are frequently but too just. But an everlasting complaining, without rhyme or reason, is a bad sign. It shows want of patience, and, indeed, want of sense. Still, of all the faults as to temper, your melancholy ladies have the worst, unless you have the same mental disease yourself. Many wives are, at times, misery makers; but these carry it on as a regular trade. They are always unhappy about something, either past, present, or to come. Both arms full of children is a pretty efficient remedy in most cases; but, if these ingredients be wanting, a little want, a little real trouble, a little genuine affliction, often will effect a cure.

12. Accomplishments

By accomplishments, I mean those things, which are usually comprehended in what is termed a useful and polite education. Now it is not unlikely that the fact of my advertising to this subject so late, may lead to the opinion that I do not set a proper estimate on this female qualification. But it is not so. Probably few set too high an estimate upon it. Its absolute importance has, I am confident, been seldom overrated. It is true I do not like a bookish woman better than a bookish man; especially a great devourer of that most contemptible species of books with whose burden the press daily groans: I mean novels. But mental cultivation, and even what is called polite learning, along with the foregoing qualifications, are a most valuable acquisition, and make every female, as well as her associates, doubly happy.

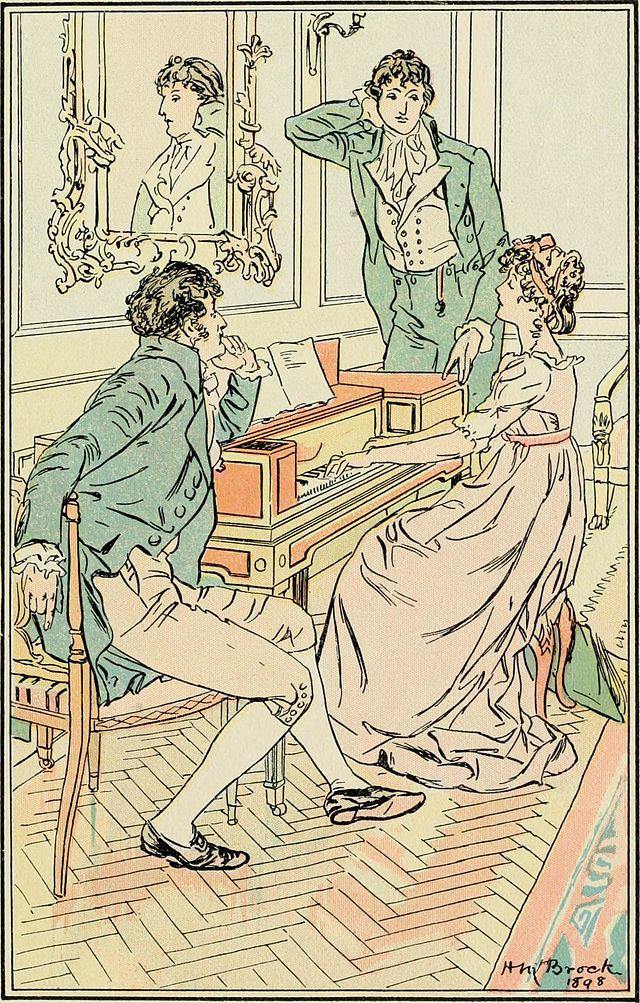

It is only when books, and music, and a taste for the fine arts are substituted for other and more important things, that they should be allowed to change love or respect to disgust. Drawing, music, embroidery, (and I might mention half a dozen other things of the same class) where they do not exclude the more useful and solid matters, may justly be regarded as appropriate branches of female education; and in some circumstances and conditions of life, indispensable. Music, -- vocal and instrumental -- and drawing, to a certain extent, seem to me desirable in all. As for dancing, I do not feel quite competent to decide. As the world is, however, I am almost disposed to reject it altogether. At any rate, if a young lady is accomplished in every other respect, you need not seriously regret that she has not attended to dancing, especially as it is conducted in most of our schools.

Enjoyed this article? If you don't want to miss a beat when it comes to Jane Austen, make sure you are signed up to the Jane Austen newsletter for exclusive updates and discounts from our Online Gift Shop.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.