In Defence of Jane Austen

by Rhian Helen Fender  “Mrs Edwards thinks you are a child still. But we know better than that, don’t we.”

“Mrs Edwards thinks you are a child still. But we know better than that, don’t we.”

So began the 2008 television adaptation of Jane Austen’s 1811 novel Sense and Sensibility, with the cad Willoughby seducing the naïve ward of heroic Colonel Brandon. The atmosphere seductive with low-light and fireplace burning, ripping bodices and whispered words... In its review, the Telegraph described how viewers tuned in “with jaws dropped, to this unexpected opening for an Austen adaptation.”

The question is, why? Why would viewers deem a sultry scene unexpected in an adaptation of the work of Austen? Austen appears to have a reputation for representing everything that is light and lovely, with the admiring Sir Walter Scott describing Pride and Prejudice (1813) as “a very pretty thing.” Austen herself seemed aware – and concerned – of her delicate reputation, stating her fear that the novel Scott so admired was “too light, and bright, and sparkling.”

Whilst it is true to state that Austen was largely focused on the lower gentry of which she was personally aware, it would be a disservice to her work to suppose she did not consider larger social influences or events, nor the more scandalous actions of those whose world she so accurately depicts. Within Austen’s novels are various themes that are often ignored or unseen when analysing her work, considered too sinister in the works of the purportedly genteel Jane Austen.

Mansfield Park (1814) tells the story of young Fanny Price, a girl able to rise above her station due to the wealth and goodwill of her extended family. The source of that power, however, is controversial due to the head of the household’s links to the slave trade. It would be an exaggeration to proclaim the novel as slavery prose – allusions to the system are rare and implicit – yet the very fact that Austen chooses to even subtly reference slavery is a bold move. The one direct reference to slavery comes as Fanny describes a family conversation with her cousins and uncle: “And I longed to do it – but there was such a dead silence. And while my cousins were sitting by without speaking a word, or seeming at all interested in the subject.”

Austen leaves it to the reader to deduce why Fanny’s family might be silent when discussing slavery – disinterest, embarrassment, shame, ignorance –and it is this empowerment of the reader in reaching their own conclusions which gives this brief passage weight. Austen does not preach to her readers, but allows them to make their own deductions. Sir Thomas Bertram’s years at his plantation in Antigua is what allows much of the action of the novel to occur – unloving marriages, flirtation and seduction – and the reader is not incorrect in supposing that Sir Thomas’s focus would have been better placed at home, rather than in underhand dealings abroad.

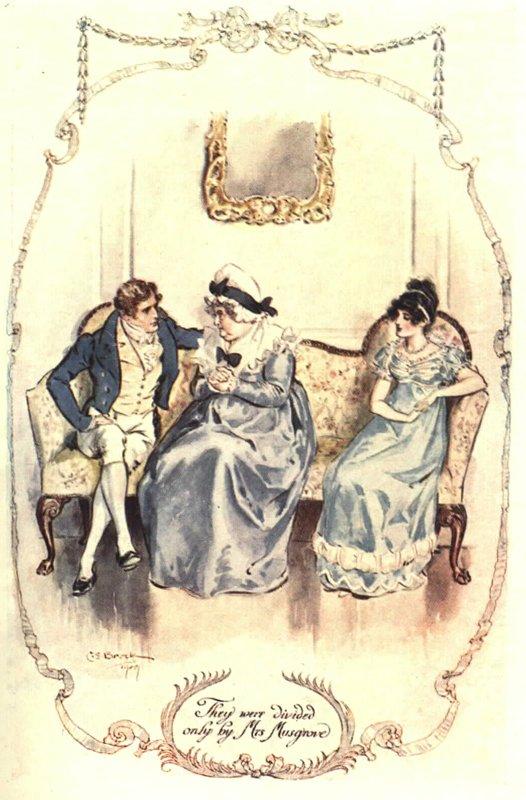

Jane Austen was writing in the context of the Napoleonic Wars, the threat and fear of an imminent French invasion rife. The local militia makes regular appearances in her novels, but it is arguably in Persuasion (1817) that the foreign threat is most tangible. When recounting his adventures at sea, Captain Wentworth is candid in his description of his ship ‘The Asp’ when stating “I knew that we should either go to the bottom together, or that she would be the making of me.” The very real possibility that brave Wentworth could have been lost to a watery grave - just “a gallant Captain Wentworth, in a small paragraph at one corner of the newspapers” - is evident in his recollections and the loss of the Musgrove brother.

The happy ending of the novel is marred by the uncertainty protagonist Anne, and indeed Austen herself, would have felt with regards to the future security of the nation: “His profession was all that could ever make her friends wish that tenderness less; the dread of a future war was all that could dim her sunshine.” Austen was concerned with the small communities her characters inhabited, but she was not unaware that foreign threats could eventually impact the Meryton and Kellynch so beloved of her characters. Austen’s settings are small: her scope is far larger than at first appears. Austen is largely known as a romantic writer.

Her characters, after some misunderstanding and trouble, find happiness together with all loose ends neatly tied-up – or do they? It is true that all protagonists appear to get their happily-ever-after but Austen was aware that not all characters were so fortunate, as she herself could personally attest. Characters such as Charlotte Lucas from Pride and Prejudice, though eventually married to the Reverend Collins, hardly enjoys what anyone could describe as the perfect ending. As Elizabeth Bennet pronounces, “Mr Collins is a conceited, pompous, narrow-minded, silly man”, and yet Charlotte was content with her acceptance of his proposal due to the security their marriage can provide. In some ways this is Charlotte’s happy ending, she has the security she so longed for, but the reader is left in no doubt when Elizabeth visits the newly-married couple that Charlotte has sacrificed passion for security, affection for money – she has settled.

Similarly, there remains a question mark over the marriage of Marianne Dashwood and Colonel Brandon. That Brandon is an honourable man devoted to Marianne is never in question, but whether that adoration is mutual is never fully resolved by the end of the novel. Austen describes how Marianne “found herself at nineteen, submitting to new attachments, entering on new duties, placed in a new home, a wife, the mistress of a family, and the patroness of a village.” This description, whilst dutiful, lacks any sense of passion that the Marianne at the beginning of the novel so yearned for, and Austen speaks of “her regard” towards Brandon – hardly a declaration of unstinting love. Whilst Austen does declare that eventually, after time, Marianne’s heart was “as much devoted to her husband, as it had once been to Willoughby” her subsequent description of Willoughby’s prolonged regret and his belief that Marianne was his “secret standard of perfection in woman” does leave the reader questioning whether, whilst a happy ending, this is not the happily-ever-after that Willoughby or Marianne would have chosen, had circumstances been different.

The refined and polite society of Jane Austen is often described as romantic, quite accurately, but that romance is not a substitute for passion. There are allusions to physical attraction and sex throughout the works of Austen. One need only look at the two characters of Willoughby and Wickham – philanderers and cads, they both attempt and sometimes succeed in seducing naïve innocents. Austen may not explicitly depict these seductions, as seen in the 2008 adaptation of Sense and Sensibility, but they very much exist.

The refined and polite society of Jane Austen is often described as romantic, quite accurately, but that romance is not a substitute for passion. There are allusions to physical attraction and sex throughout the works of Austen. One need only look at the two characters of Willoughby and Wickham – philanderers and cads, they both attempt and sometimes succeed in seducing naïve innocents. Austen may not explicitly depict these seductions, as seen in the 2008 adaptation of Sense and Sensibility, but they very much exist.

The repressed emotions of characters is a common theme throughout all the novels, and at times this physical attraction begins to manifest itself in subtle ways. Captain Wentworth’s momentary placing of Anne Elliot in a carriage leaves Anne flustered at the thought that “his hands had done it,” whilst his touch when taking a child from her leaves her “perfectly speechless.” At times physical attraction is not shown through touch but through the gaze. When first meeting Elizabeth Bennet, Mr Darcy’s response is detailed by Austen: “Turning round, he looked for a moment at Elizabeth, till catching her eye, he withdrew his.” What Austen is subtly alluding to is that Darcy wanted Elizabeth to be conscious of his physical scrutiny, to know she was an object of his assessing gaze.

Indeed, whilst his love for Elizabeth is pure, there is no denying that Darcy’s admiration for Elizabeth is also highly sexualised. Whether referencing her “fine eyes” or stationing himself “so as to command a full view of the fair performer’s countenance,” Darcy enjoys the “light and pleasing” figure of Elizabeth. This physical attraction does not detract from the romance of Austen’s novels; it adds to it. Unmarried though she may have been, as a woman who had enjoyed conversing, socialising and flirting with men, Austen would have been fully aware that attraction takes many forms, and all are accounted for within her prose.

Charlotte Bronte, a continuous critic of the works of Austen, once said upon reading Pride and Prejudice: “And what did I find?... a commonplace face; a carefully fenced, highly cultivated garden, with neat borders and delicate flowers; but no glance of a bright vivid physiognomy, no open country, no fresh air no blue hill, no boony beck.” Whilst the work of the Bronte sisters was undoubtedly darker, with the sweeping moors and gut-wrenching pain and betrayal of protagonists, what they – and many avid Austen fans – fail to understand is that this does not make Austen’s differing style mediocre, inferior in theme or plot. As admirer E. M. Forster stated, many readers of Austen “like all regular churchgoers… scarcely notice what is being said.”

The subtle allusions to slavery, the impending doom of war, the sexual connotations and repressed emotions and attraction are all evident in Austen, if one only looks for them. Henry Crawford’s seduction of Maria Bertram is every bit as wicked as Heathcliff’s stalking of Isabella Linton in Wuthering Heights. The incessant longing of Captain Wentworth and Anne Elliot is reminiscent of the separation between Mr Rochester and Jane Eyre. Whilst there are many bright and romantic moments within Austen, she is not ignorant of, nor unconcerned with, the darker and more sinister aspects of both the characters and the society which they inhabit. Much like her first title for Pride and Prejudice, it is the first impressions of the novels of Austen that are misleading. Genteel and sheltered she may have been, but look beneath the surface and the underworld of Regency society is there to see, proving Austen to be a more informed and passionate author then she is often given credit for. It is perhaps Virginia Woolf who best described Jane Austen when she stated that “Of all great writers she is the most difficult to catch in the act of greatness.”

Rhian Helen Fender's love of the novels of Jane Austen began after a chance viewing of the 1995 BBC Pride and Prejudice adaptation. This admiration for the literary works has led to her enjoyment of many adaptations, sequels and spin-offs, as well as re-reading the original texts many times over. This interest has very much shaped her academic studies, resulting in the final thesis of her history degree exploring the changing ideal of masculinity during the nineteenth-century.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.