The Stuart Jacobite Kings: A Biography by Kathleen Spaltro

Many who have read Jane Austen's History of England will have recognized that Jane was an avid supporter of the Royal House of Stuart and the Jacobite cause (the movement took its name from Jacobus, the Latinised form of James.) What most will not realize is that through service to Charles I, her relative, Thomas Leigh of Stoneleigh Abbey, was elevated to the nobility (July 1643), becoming afterwards known as Lord Leigh. With this family connection and the recent interest in the Jacobite cause, it seems only reasonable to include this in depth look at the events surrounding the romantic character of "Bonnie Prince Charlie" and the rise of the Hanoverian Kings, beginning with George I.

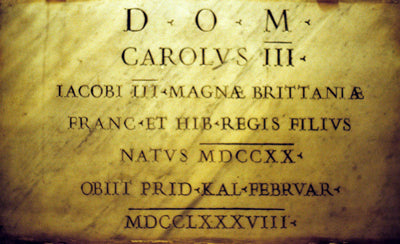

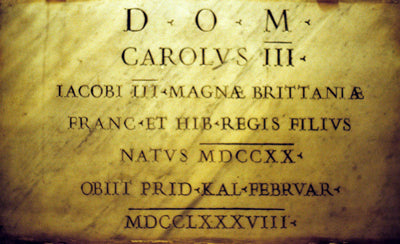

James Francis Edward felt compelled to assert his right as Prince of Wales to the British throne stolen from his father and made many plans that finally culminated in his three campaigns of 1708, 1715, and 1719. His own withdrawn personality and frequent malarial illnesses proved detrimental to military success. Nicknamed “Old Mr. Melancholy” or "Old Mr. Misfortune" by English satirists, James Francis Edward seemed lethargic, depressed, and uninspiring to his followers in Scotland. As one Jacobite Scot recorded, “we found ourselves not at all animated by his presence; if he was disappointed in us, we were tenfold more so in him. We saw nothing in him that looked like spirit. . . . Some said the circumstances he found us in dejected him; I am sure the figure he made dejected us.” In 1745, the far more athletic and extroverted Bonnie Prince Charlie would spark a very different reaction. Yet, while Charles Edward proved himself the better leader of men at arms, James Francis Edward would have made the better King and was the better man. The conscientiousness that drove James Francis Edward to assert his father’s right would have driven him also to rule well. In addition, he had none of the religious bigotry that had hardened James II’s subjects against him. In fact, the dying James II advised James Francis Edward to establish liberty of conscience upon his restoration. James Francis Edward himself wrote, “I am a Catholic, but I am a King, and subjects, of whatever religion they may be, have an equal right to be protected. I am a King, but as the Pope himself told me, I am not an Apostle.” Yet, at the same time, James Francis Edward utterly refused to listen to any persuasion that he should change his own religion in order to become King more easily. (In 1701, the Act of Settlement sought to ensure a Protestant succession and to exclude his claim. Heirs to the throne must themselves be Protestants, and they must not marry Catholics.) In contrast, Charles Edward eventually became an Anglican for such opportunistic reasons. Surely, James Francis Edward revealed himself as the more principled man of the two. His greater strength of character showed, too, in his reaction to the failure of the Jacobite risings in which he himself took part. While after 1746 Bonnie Prince Charlie brooded over defeat and drank himself into a stupefied and miserable middle age, James Francis Edward after 1719 for the most part shelved any ideas about active campaigning and lived a new life in Italy. Born in St. James’s Palace in London, he had lived but a few weeks on his native soil before his parents’ 1688 exile led them to seek refuge with James II’s first cousin, Louis XIV of France. Louis had housed his cousins in St-Germain-en-Laye, twelve miles west of Paris and not far from Versailles. Although Louis recognized James Francis Edward as the rightful King of Great Britain in 1701, the Treaty of Utrecht (1713-1714) forced Louis to expel James Francis Edward from French soil. After the subsequent failure of the Fifteen, James Francis Edward wandered—to Lorraine, to Avignon (then papal territory), to various places in Italy, then finally to Rome and Urbino. A sympathetic Pope Clement XI gave the exile a pension and allowed him to live in Palazzo Muti in Rome, near Santi Apostoli. Clement also lent Palazzo Savelli at Albano as a summer home. By accepting refuge in Rome, James Francis Edward effectively surrendered any hope of gaining the Protestant support vital to his restoration. After 1719, he still claimed to rule as “James III” and indulged in some intrigue but essentially made another life for himself for the next 45 years. The scene had shifted to Rome internally as well as externally. His marriage in 1719 to Princess Clementina of Poland, granddaughter of John III Sobieski and goddaughter of Clement XI, produced two sons: Charles Edward, born in 1720, and Henry Benedict, born in 1725. So uninterested was James Francis Edward in further Jacobite risings that Charles Edward told him of the Forty-five in a letter written on the day Charles Edward sailed for Scotland. James Francis Edward reacted with dismay, “Heaven forbid that all the crowns of the world should rob me of my son.”

James Francis Edward felt compelled to assert his right as Prince of Wales to the British throne stolen from his father and made many plans that finally culminated in his three campaigns of 1708, 1715, and 1719. His own withdrawn personality and frequent malarial illnesses proved detrimental to military success. Nicknamed “Old Mr. Melancholy” or "Old Mr. Misfortune" by English satirists, James Francis Edward seemed lethargic, depressed, and uninspiring to his followers in Scotland. As one Jacobite Scot recorded, “we found ourselves not at all animated by his presence; if he was disappointed in us, we were tenfold more so in him. We saw nothing in him that looked like spirit. . . . Some said the circumstances he found us in dejected him; I am sure the figure he made dejected us.” In 1745, the far more athletic and extroverted Bonnie Prince Charlie would spark a very different reaction. Yet, while Charles Edward proved himself the better leader of men at arms, James Francis Edward would have made the better King and was the better man. The conscientiousness that drove James Francis Edward to assert his father’s right would have driven him also to rule well. In addition, he had none of the religious bigotry that had hardened James II’s subjects against him. In fact, the dying James II advised James Francis Edward to establish liberty of conscience upon his restoration. James Francis Edward himself wrote, “I am a Catholic, but I am a King, and subjects, of whatever religion they may be, have an equal right to be protected. I am a King, but as the Pope himself told me, I am not an Apostle.” Yet, at the same time, James Francis Edward utterly refused to listen to any persuasion that he should change his own religion in order to become King more easily. (In 1701, the Act of Settlement sought to ensure a Protestant succession and to exclude his claim. Heirs to the throne must themselves be Protestants, and they must not marry Catholics.) In contrast, Charles Edward eventually became an Anglican for such opportunistic reasons. Surely, James Francis Edward revealed himself as the more principled man of the two. His greater strength of character showed, too, in his reaction to the failure of the Jacobite risings in which he himself took part. While after 1746 Bonnie Prince Charlie brooded over defeat and drank himself into a stupefied and miserable middle age, James Francis Edward after 1719 for the most part shelved any ideas about active campaigning and lived a new life in Italy. Born in St. James’s Palace in London, he had lived but a few weeks on his native soil before his parents’ 1688 exile led them to seek refuge with James II’s first cousin, Louis XIV of France. Louis had housed his cousins in St-Germain-en-Laye, twelve miles west of Paris and not far from Versailles. Although Louis recognized James Francis Edward as the rightful King of Great Britain in 1701, the Treaty of Utrecht (1713-1714) forced Louis to expel James Francis Edward from French soil. After the subsequent failure of the Fifteen, James Francis Edward wandered—to Lorraine, to Avignon (then papal territory), to various places in Italy, then finally to Rome and Urbino. A sympathetic Pope Clement XI gave the exile a pension and allowed him to live in Palazzo Muti in Rome, near Santi Apostoli. Clement also lent Palazzo Savelli at Albano as a summer home. By accepting refuge in Rome, James Francis Edward effectively surrendered any hope of gaining the Protestant support vital to his restoration. After 1719, he still claimed to rule as “James III” and indulged in some intrigue but essentially made another life for himself for the next 45 years. The scene had shifted to Rome internally as well as externally. His marriage in 1719 to Princess Clementina of Poland, granddaughter of John III Sobieski and goddaughter of Clement XI, produced two sons: Charles Edward, born in 1720, and Henry Benedict, born in 1725. So uninterested was James Francis Edward in further Jacobite risings that Charles Edward told him of the Forty-five in a letter written on the day Charles Edward sailed for Scotland. James Francis Edward reacted with dismay, “Heaven forbid that all the crowns of the world should rob me of my son.”  After the disaster of the Forty-five, James Francis Edward showed again how little he thought of Jacobite aspirations when in 1747 he supported his son Henry’s being made a Cardinal of the Catholic Church. Alive to the political consequences of this event, enraged by what he saw as his father’s and brother’s betrayal of the Jacobite cause, Charles Edward never saw James Francis Edward again. While Charles Edward wrote to his father from time to time, he maintained a total estrangement from his brother Henry for 18 years. Henry re-established contact with Charles Edward as their aging father declined, but Charles Edward refused to visit until Pope Clement XIII recognized his rights to the throne as James Francis Edward’s heir. James Francis Edward died in 1766 as Charles Edward preserved a stubborn absence that had lasted 22 years. After honorably asserting his claim, James Francis Edward sensibly recognized the futility of further assertion. And yet, sensible as his turning away from Jacobitism seems, the romance of his being the “Chevalier de Saint George” or “the King over the Water” still lingers. The rising of 1708 acted against James Francis Edward’s half-sister Queen Anne, who had succeeded William and Mary. Angered by his action into terming James Francis Edward “the Pretender,” Anne nevertheless sought to give the impression at times that she preferred her half-brother to any other successor, especially the detested Hanoverians specified by the 1701 Act of Settlement.

After the disaster of the Forty-five, James Francis Edward showed again how little he thought of Jacobite aspirations when in 1747 he supported his son Henry’s being made a Cardinal of the Catholic Church. Alive to the political consequences of this event, enraged by what he saw as his father’s and brother’s betrayal of the Jacobite cause, Charles Edward never saw James Francis Edward again. While Charles Edward wrote to his father from time to time, he maintained a total estrangement from his brother Henry for 18 years. Henry re-established contact with Charles Edward as their aging father declined, but Charles Edward refused to visit until Pope Clement XIII recognized his rights to the throne as James Francis Edward’s heir. James Francis Edward died in 1766 as Charles Edward preserved a stubborn absence that had lasted 22 years. After honorably asserting his claim, James Francis Edward sensibly recognized the futility of further assertion. And yet, sensible as his turning away from Jacobitism seems, the romance of his being the “Chevalier de Saint George” or “the King over the Water” still lingers. The rising of 1708 acted against James Francis Edward’s half-sister Queen Anne, who had succeeded William and Mary. Angered by his action into terming James Francis Edward “the Pretender,” Anne nevertheless sought to give the impression at times that she preferred her half-brother to any other successor, especially the detested Hanoverians specified by the 1701 Act of Settlement.  As Anne’s health declined a few years later, the Jacobite James Douglas, 4th Duke of Hamilton, wanted James Francis Edward in Scotland to await the Queen’s death. James Fitzjames, 1st Duke of Berwick (a bastard of James II by Arabella Churchill), planned to have James Francis Edward meet their half-sister Queen Anne in London. Hamilton’s suspicious death in a duel aborted such plans, and the throne passed to the Hanoverian descendants of Elizabeth of Bohemia. The risings of 1715 and 1719 (against George I), and of 1745 (against George II) failed to dislodge them. With Hamilton’s death in 1712 and Anne’s death in 1714, the opportunity for reconciliation and restoration had died as well. A brilliant rendering of Jacobite intrigue complete with an unflattering, unfair, and unforgettable view of James Francis Edward, Thackeray’s historical novel Henry Esmond portrays this lost moment—and all the Jacobite strivings—in all their comedy, tragedy, romance, and futility.

As Anne’s health declined a few years later, the Jacobite James Douglas, 4th Duke of Hamilton, wanted James Francis Edward in Scotland to await the Queen’s death. James Fitzjames, 1st Duke of Berwick (a bastard of James II by Arabella Churchill), planned to have James Francis Edward meet their half-sister Queen Anne in London. Hamilton’s suspicious death in a duel aborted such plans, and the throne passed to the Hanoverian descendants of Elizabeth of Bohemia. The risings of 1715 and 1719 (against George I), and of 1745 (against George II) failed to dislodge them. With Hamilton’s death in 1712 and Anne’s death in 1714, the opportunity for reconciliation and restoration had died as well. A brilliant rendering of Jacobite intrigue complete with an unflattering, unfair, and unforgettable view of James Francis Edward, Thackeray’s historical novel Henry Esmond portrays this lost moment—and all the Jacobite strivings—in all their comedy, tragedy, romance, and futility.

Granddaughter of the Polish King John III Sobieski and goddaughter of Pope Clement XI, the 17-year-old Clementina married James Francis Edward in 1719. Doing a favor for George I, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI had sought to prevent the marriage by arresting Clementina at Innsbruck; from there, she made a daring escape with the help of James Francis Edward’s supporters and then married him by proxy in Bologna. She gave birth to Charles Edward in 1720 and to Henry Benedict in 1725. During these early years of the family’s long sojourn in Palazzo Muti in Rome, husband’s and wife’s initial delight in each other soured with familiarity. A power struggle evolved over the Protestant members of James Francis Edward’s household. Although the Pope scolded Clementina for her intolerance, she feared their influence over her sons. Failing to sway her husband, Clementina ran away to the Ursuline convent at Santa Cecilia in Trastevere. James Francis Edward lost financial and political support because his alleged but unlikely adultery supposedly provoked her flight. Clementina stubbornly stayed in her convent for many months until the Pope told her she might be forbidden the sacraments unless she returned to her husband. In 1727, she finally complied, but a much-changed woman now lived in Palazzo Muti. She had become extremely devout, compulsive in her religious observances, and so stringent in her fasting that she ate alongside the family at a small table holding scanty portions of specially prepared meals. An emaciated 33-year old Clementina died in 1735. Perhaps anorexia served as a defiant, if self-destructive, response to her perceived powerlessness in her household and contributed largely to her death.

Granddaughter of the Polish King John III Sobieski and goddaughter of Pope Clement XI, the 17-year-old Clementina married James Francis Edward in 1719. Doing a favor for George I, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI had sought to prevent the marriage by arresting Clementina at Innsbruck; from there, she made a daring escape with the help of James Francis Edward’s supporters and then married him by proxy in Bologna. She gave birth to Charles Edward in 1720 and to Henry Benedict in 1725. During these early years of the family’s long sojourn in Palazzo Muti in Rome, husband’s and wife’s initial delight in each other soured with familiarity. A power struggle evolved over the Protestant members of James Francis Edward’s household. Although the Pope scolded Clementina for her intolerance, she feared their influence over her sons. Failing to sway her husband, Clementina ran away to the Ursuline convent at Santa Cecilia in Trastevere. James Francis Edward lost financial and political support because his alleged but unlikely adultery supposedly provoked her flight. Clementina stubbornly stayed in her convent for many months until the Pope told her she might be forbidden the sacraments unless she returned to her husband. In 1727, she finally complied, but a much-changed woman now lived in Palazzo Muti. She had become extremely devout, compulsive in her religious observances, and so stringent in her fasting that she ate alongside the family at a small table holding scanty portions of specially prepared meals. An emaciated 33-year old Clementina died in 1735. Perhaps anorexia served as a defiant, if self-destructive, response to her perceived powerlessness in her household and contributed largely to her death.  Charles supposedly resembled his mother in temperament, while Henry resembled their father. As the boys grew to manhood without their mother, the athletic Charles trained himself to lead a Jacobite rebellion by hunting, shooting, hiking in bare feet, and reading military manuals. Early in his own life, Henry became extremely observant of his religion, just as their father became after Clementina’s death. The European political situation seemed to offer Charles an opening. France sought a way to hamper George II from helping Austria during the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48). A Jacobite rising in Scotland might serve as an effective means. Promises of French support proved equivocal, however, and James Francis Edward distrusted them out of long experience. Determined to go ahead even without French support, Charles announced his embarking for Scotland in a letter written to his father on the very day he gallantly landed with a tiny force in the Hebrides, on the island of Eriskay, at a place later called “the Prince’s Strand.” With charm, courage, gallantry, and persuasiveness—by sheer force of personality—he stirred the reluctant Highlanders not only to recognize his claim but also to fight for it. Later the Jacobite Lord Balmerino at his own execution testified about Charles: “the incomparable sweetness of his nature, his affability, his compassion, his justice, his temperance, his patience, and his courage are virtues, seldom to be found in one person.” Resentful of the 1707 Union with England that had ended Scotland’s status as a discrete nation with its own Parliament, the clan chiefs sought to restore the Stuarts to a Scottish throne and to achieve Scottish independence. Charles succeeded with the Highlanders’ help in mastering Scotland, but his desire to invade England met with Highlander misgivings and resistance. Eventually, his officers argued for a retreat to Scotland, where William Augustus, the Duke of Cumberland and the son of George II, routed Charles’s troops at Culloden Moor in April, 1746. A hunted fugitive until he escaped to France in September, 1746, Charles received much help from such supporters as Flora Macdonald during his perilous journey to safety.

Charles supposedly resembled his mother in temperament, while Henry resembled their father. As the boys grew to manhood without their mother, the athletic Charles trained himself to lead a Jacobite rebellion by hunting, shooting, hiking in bare feet, and reading military manuals. Early in his own life, Henry became extremely observant of his religion, just as their father became after Clementina’s death. The European political situation seemed to offer Charles an opening. France sought a way to hamper George II from helping Austria during the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48). A Jacobite rising in Scotland might serve as an effective means. Promises of French support proved equivocal, however, and James Francis Edward distrusted them out of long experience. Determined to go ahead even without French support, Charles announced his embarking for Scotland in a letter written to his father on the very day he gallantly landed with a tiny force in the Hebrides, on the island of Eriskay, at a place later called “the Prince’s Strand.” With charm, courage, gallantry, and persuasiveness—by sheer force of personality—he stirred the reluctant Highlanders not only to recognize his claim but also to fight for it. Later the Jacobite Lord Balmerino at his own execution testified about Charles: “the incomparable sweetness of his nature, his affability, his compassion, his justice, his temperance, his patience, and his courage are virtues, seldom to be found in one person.” Resentful of the 1707 Union with England that had ended Scotland’s status as a discrete nation with its own Parliament, the clan chiefs sought to restore the Stuarts to a Scottish throne and to achieve Scottish independence. Charles succeeded with the Highlanders’ help in mastering Scotland, but his desire to invade England met with Highlander misgivings and resistance. Eventually, his officers argued for a retreat to Scotland, where William Augustus, the Duke of Cumberland and the son of George II, routed Charles’s troops at Culloden Moor in April, 1746. A hunted fugitive until he escaped to France in September, 1746, Charles received much help from such supporters as Flora Macdonald during his perilous journey to safety.  In France, Charles found that defeat increased equivocation exponentially. Henry (and their father) understood that Jacobite hopes had died at Culloden, but Charles obstinately insisted on living as though those hopes were realizable. He refused to leave France after the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle specified that Pretenders to the British throne could not reside in Britain, France, Holland, Germany, Spain, or Genoa; Louis XV had to expel Charles by force. After a stay in papal Avignon, Charles went underground for almost 20 years. Wandering through Europe in disguise, he even made secret visits to England in 1750 and later. In London in 1750, he became an Anglican, probably out of political calculation. Henry heard nothing from Charles and James Francis Edward very little, because Charles had felt enraged by Henry’s becoming a Cardinal in 1747. Although at that time Cardinals need not be priests, Henry chose ordination in 1748. His ecclesiastical career proceeded as he became a Cardinal-Priest in 1752; the Camerlengo in charge of the papal conclave in 1758; Cardinal-Bishop with a see in Frascati in 1761; and Vice-Chancellor of the Church in 1763. Before abolishing the Jesuit order in 1773, Pope Clement XIV put Henry in charge of the Jesuit seminary at Frascati and made him an investigator of the Jesuit seminary in Rome.

In France, Charles found that defeat increased equivocation exponentially. Henry (and their father) understood that Jacobite hopes had died at Culloden, but Charles obstinately insisted on living as though those hopes were realizable. He refused to leave France after the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle specified that Pretenders to the British throne could not reside in Britain, France, Holland, Germany, Spain, or Genoa; Louis XV had to expel Charles by force. After a stay in papal Avignon, Charles went underground for almost 20 years. Wandering through Europe in disguise, he even made secret visits to England in 1750 and later. In London in 1750, he became an Anglican, probably out of political calculation. Henry heard nothing from Charles and James Francis Edward very little, because Charles had felt enraged by Henry’s becoming a Cardinal in 1747. Although at that time Cardinals need not be priests, Henry chose ordination in 1748. His ecclesiastical career proceeded as he became a Cardinal-Priest in 1752; the Camerlengo in charge of the papal conclave in 1758; Cardinal-Bishop with a see in Frascati in 1761; and Vice-Chancellor of the Church in 1763. Before abolishing the Jesuit order in 1773, Pope Clement XIV put Henry in charge of the Jesuit seminary at Frascati and made him an investigator of the Jesuit seminary in Rome.  Addressed as “Your Royal Highness and Eminence,” the Cardinal Duke of York made his home at the Palace of LaRocca in Frascati, with a summer home at Villa Muti outside Frascati. After he became Vice-Chancellor, he lived at Palazzo Cancelleria when in Rome. His large income derived from ecclesiastical offices in Flanders, Spain, Naples, France, and Spanish America, especially Mexico, where he owned land. Henry supported many Jacobites and eased the plight of Frascati’s poor. Nicholas Cardinal Wiseman, Archbishop of Westminster, later remarked of Henry, “to a royal heart he was no pretender. His charities were without bounds: poverty and distress were unknown in his see.”

Addressed as “Your Royal Highness and Eminence,” the Cardinal Duke of York made his home at the Palace of LaRocca in Frascati, with a summer home at Villa Muti outside Frascati. After he became Vice-Chancellor, he lived at Palazzo Cancelleria when in Rome. His large income derived from ecclesiastical offices in Flanders, Spain, Naples, France, and Spanish America, especially Mexico, where he owned land. Henry supported many Jacobites and eased the plight of Frascati’s poor. Nicholas Cardinal Wiseman, Archbishop of Westminster, later remarked of Henry, “to a royal heart he was no pretender. His charities were without bounds: poverty and distress were unknown in his see.”  Realizing the impracticality of a Jacobite restoration, Henry had entered upon a notably successful ecclesiastical career, while his brother, a determined Jacobite to the end, wandered through Europe in disguise. Their aging father, to whom Charles wrote occasionally, served as a tenuous link between the severed brothers. In 1765, Henry notified Charles of James Francis Edward’s decline and approaching death, but Charles refused to visit until the Pope recognized Charles’s royal claims. The father died without seeing again his prodigal son, and Charles returned in 1766 to live in Palazzo Muti in Rome. Although he now assumed the name of “Charles III,” he received little official recognition of his title and reluctantly accepted being called “Count of Albany.” (“Albany” was the traditional title of the second son of the King of Scotland.) Henry gave Charles Henry’s rights to their father’s papal pension. Although their father’s death had reunited the brothers, many crises strained their relationship. During his wandering years, Charles had lived with Clementina Walkinshaw, who had given birth to his daughter Charlotte. In 1760, Clementina ran away from Charles and took their daughter with her. “You pushed me to the greatest extremity, and even despair,” she wrote to him, “as I was always in perpetual dread of my life from your violent passions.”

Realizing the impracticality of a Jacobite restoration, Henry had entered upon a notably successful ecclesiastical career, while his brother, a determined Jacobite to the end, wandered through Europe in disguise. Their aging father, to whom Charles wrote occasionally, served as a tenuous link between the severed brothers. In 1765, Henry notified Charles of James Francis Edward’s decline and approaching death, but Charles refused to visit until the Pope recognized Charles’s royal claims. The father died without seeing again his prodigal son, and Charles returned in 1766 to live in Palazzo Muti in Rome. Although he now assumed the name of “Charles III,” he received little official recognition of his title and reluctantly accepted being called “Count of Albany.” (“Albany” was the traditional title of the second son of the King of Scotland.) Henry gave Charles Henry’s rights to their father’s papal pension. Although their father’s death had reunited the brothers, many crises strained their relationship. During his wandering years, Charles had lived with Clementina Walkinshaw, who had given birth to his daughter Charlotte. In 1760, Clementina ran away from Charles and took their daughter with her. “You pushed me to the greatest extremity, and even despair,” she wrote to him, “as I was always in perpetual dread of my life from your violent passions.”  James Francis Edward, and later Henry, supported mother and daughter because Charles would not do so. In 1772, Charles married Louise of Stolberg-Gedern, granddaughter of a Prince of the Holy Roman Empire. The marriage quickly deteriorated while they lived in Palazzo Guadigni in Florence; as an English observer commented in 1779, “she has paid dearly for the dregs of royalty.” As jealous of Louise as he had been of Clementina, Charles reverted to his pattern of physical abuse in a drunken rage on St. Andrew’s Day in 1780. He apparently also raped his wife because he suspected her of adultery with the Italian poet Count Vittorio Alfieri, whose muse Louise had been.

James Francis Edward, and later Henry, supported mother and daughter because Charles would not do so. In 1772, Charles married Louise of Stolberg-Gedern, granddaughter of a Prince of the Holy Roman Empire. The marriage quickly deteriorated while they lived in Palazzo Guadigni in Florence; as an English observer commented in 1779, “she has paid dearly for the dregs of royalty.” As jealous of Louise as he had been of Clementina, Charles reverted to his pattern of physical abuse in a drunken rage on St. Andrew’s Day in 1780. He apparently also raped his wife because he suspected her of adultery with the Italian poet Count Vittorio Alfieri, whose muse Louise had been.  In a reprise of the events of 55 years before, Louise ran away to the Convent of the White Nuns in Florence, and she turned the Pope and Henry against Charles. Henry even arranged for her to stay in Rome in the same Ursuline convent where his mother had sought refuge, but Louise eventually preferred to live in Palazzo Cancelleria. Henry did not become fully reconciled to Charles until after Charles in 1784 legitimized his daughter Charlotte, named her Duchess of Albany, and asked her to care for him in his decrepit middle age. Having developed a habit of drinking six bottles of Cyprus wine after dinner, Charles obviously needed a caretaker. To her credit, Charlotte took good care of her previously neglectful father, though he tried her patience. She exasperatedly noted that he resembled a fifteen-year-old boy.

In a reprise of the events of 55 years before, Louise ran away to the Convent of the White Nuns in Florence, and she turned the Pope and Henry against Charles. Henry even arranged for her to stay in Rome in the same Ursuline convent where his mother had sought refuge, but Louise eventually preferred to live in Palazzo Cancelleria. Henry did not become fully reconciled to Charles until after Charles in 1784 legitimized his daughter Charlotte, named her Duchess of Albany, and asked her to care for him in his decrepit middle age. Having developed a habit of drinking six bottles of Cyprus wine after dinner, Charles obviously needed a caretaker. To her credit, Charlotte took good care of her previously neglectful father, though he tried her patience. She exasperatedly noted that he resembled a fifteen-year-old boy.  Charlotte also effected a reconciliation of Charles with Henry. Charles returned to Rome in 1785 to live once again in Palazzo Muti, this time with Charlotte. When he had lived there with Louise before they moved to Florence, the Romans had called her their “Queen of Hearts.” Three years later, after Charles died, Henry, tears streaming down his face, conducted a private royal burial in Frascati. (The public royal funeral held for James Francis Edward was not permitted for Charles.) He sent a Memorial to foreign courts asserting his claim to be Henry IX and the right of his named successor Charles Emmanuel IV, King of Sardinia (a descendant of Henrietta Stuart, sister of James II). Other than honorably keeping faith with his dead by asserting their and his claim, Henry made no move to effect a Jacobite restoration after forty years’ realization of its futility. The 1796 Napoleonic invasion of Italy, with its threat to the Papacy, caused the Cardinal King to donate much of his fortune to preserve the Holy See. Two years later, the fortunes of war caused Henry to flee from his beloved Frascati to Naples, then to Sicily, then to Venice in order to hold a conclave to elect a successor to Pope Pius VI. In the meantime, Henry’s wealth had vanished. His friends sent an appeal to Prime Minister William Pitt, who informed George III. Henry’s Hanoverian cousin sent immediate financial relief and instituted a pension for life in 1800. (Pitt probably never told George III that the British government actually owed over ₤1 million to this heir of James II's Queen Mary of Modena.) The Cardinal King appreciated this kindness (as well as the friendly and gracious encounters he had had with George III’s son, Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex, who insisted on addressing the Cardinal as "Your Royal Highness," a courtesy reciprocated by Henry). In his will, he left to the Prince of Wales (later George IV) the British crown jewels carried by James II and Queen Mary Beatrice in their 1688 flight from England.

Charlotte also effected a reconciliation of Charles with Henry. Charles returned to Rome in 1785 to live once again in Palazzo Muti, this time with Charlotte. When he had lived there with Louise before they moved to Florence, the Romans had called her their “Queen of Hearts.” Three years later, after Charles died, Henry, tears streaming down his face, conducted a private royal burial in Frascati. (The public royal funeral held for James Francis Edward was not permitted for Charles.) He sent a Memorial to foreign courts asserting his claim to be Henry IX and the right of his named successor Charles Emmanuel IV, King of Sardinia (a descendant of Henrietta Stuart, sister of James II). Other than honorably keeping faith with his dead by asserting their and his claim, Henry made no move to effect a Jacobite restoration after forty years’ realization of its futility. The 1796 Napoleonic invasion of Italy, with its threat to the Papacy, caused the Cardinal King to donate much of his fortune to preserve the Holy See. Two years later, the fortunes of war caused Henry to flee from his beloved Frascati to Naples, then to Sicily, then to Venice in order to hold a conclave to elect a successor to Pope Pius VI. In the meantime, Henry’s wealth had vanished. His friends sent an appeal to Prime Minister William Pitt, who informed George III. Henry’s Hanoverian cousin sent immediate financial relief and instituted a pension for life in 1800. (Pitt probably never told George III that the British government actually owed over ₤1 million to this heir of James II's Queen Mary of Modena.) The Cardinal King appreciated this kindness (as well as the friendly and gracious encounters he had had with George III’s son, Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex, who insisted on addressing the Cardinal as "Your Royal Highness," a courtesy reciprocated by Henry). In his will, he left to the Prince of Wales (later George IV) the British crown jewels carried by James II and Queen Mary Beatrice in their 1688 flight from England.  Henry’s 1802 will also left his claim to the King of Sardinia (of the House of Savoy), the claim eventually by a tangled chain being passed to the Dukes of Bavaria. In 1803, as the most senior Cardinal, the Cardinal King became Dean of the College of Cardinals. Four years later, he died on the 46th anniversary of his being made Bishop of Frascati. While Charles had spoiled more than 40 years by making undignified attempts to preserve his royal dignity, Henry merely called himself King non desideriis hominum sed voluntate Dei—“not by the desire of man but by the will of God.” Endearingly, Henry did insist, however, that the stray King Charles spaniel that glued itself to him one day at St. Peter’s had instinctively recognized him as a royal Stuart.

Henry’s 1802 will also left his claim to the King of Sardinia (of the House of Savoy), the claim eventually by a tangled chain being passed to the Dukes of Bavaria. In 1803, as the most senior Cardinal, the Cardinal King became Dean of the College of Cardinals. Four years later, he died on the 46th anniversary of his being made Bishop of Frascati. While Charles had spoiled more than 40 years by making undignified attempts to preserve his royal dignity, Henry merely called himself King non desideriis hominum sed voluntate Dei—“not by the desire of man but by the will of God.” Endearingly, Henry did insist, however, that the stray King Charles spaniel that glued itself to him one day at St. Peter’s had instinctively recognized him as a royal Stuart.

Part One:

Call your companions, Launch your vessel, And crowd your canvas, And, ere it vanishes Over the margin, After it, follow it, Follow The Gleam. --Alfred Lord TennysonShortly after the 1688 birth of James Francis Edward to James II of Great Britain and Queen Mary Beatrice, James II lost his crown to his daughter and her husband. The birth of a Catholic Prince of Wales precipitated the expulsion of his Catholic parents by the “Glorious Revolution” that enthroned the Protestants William III and Mary II. Resisting his overthrow, in 1689-1690 the expelled James II challenged William in Ireland and Scotland, but his challenges failed. After the death of James II in 1701, his son James Francis Edward and, later, his grandsons Charles Edward and Henry all in turn inherited and proclaimed their right to rule Great Britain. For a century, “Jacobites” argued, schemed, conspired, fought, and died on their behalf. Each of these three very different men struggled with his entangling legacy of denied kingship, either allowing the dream of restoration to dominate his life or making another life quite immune from its seductive pull, for the dream could become very nightmarish indeed. James Francis Edward both felt and resisted the pull of the dream. An introverted and conscientious man, James Francis Edward agreed to three attempts at his restoration: two aborted efforts in 1708 and 1719 that bookended his all-out Scottish campaign in 1715 (called “the Fifteen”). Thirty years later, his more dynamic son Charles Edward (“Bonnie Prince Charlie”) enthralled the Scottish clans in “the Forty-five.” All of these major Jacobite rebellions depended for their success on Continental support and British discontent holding steady just when competent generalship was available and the weather agreed with their purpose. Such a happy conjunction of forces, however, never held long enough to effect a Jacobite restoration.

James Francis Edward felt compelled to assert his right as Prince of Wales to the British throne stolen from his father and made many plans that finally culminated in his three campaigns of 1708, 1715, and 1719. His own withdrawn personality and frequent malarial illnesses proved detrimental to military success. Nicknamed “Old Mr. Melancholy” or "Old Mr. Misfortune" by English satirists, James Francis Edward seemed lethargic, depressed, and uninspiring to his followers in Scotland. As one Jacobite Scot recorded, “we found ourselves not at all animated by his presence; if he was disappointed in us, we were tenfold more so in him. We saw nothing in him that looked like spirit. . . . Some said the circumstances he found us in dejected him; I am sure the figure he made dejected us.” In 1745, the far more athletic and extroverted Bonnie Prince Charlie would spark a very different reaction. Yet, while Charles Edward proved himself the better leader of men at arms, James Francis Edward would have made the better King and was the better man. The conscientiousness that drove James Francis Edward to assert his father’s right would have driven him also to rule well. In addition, he had none of the religious bigotry that had hardened James II’s subjects against him. In fact, the dying James II advised James Francis Edward to establish liberty of conscience upon his restoration. James Francis Edward himself wrote, “I am a Catholic, but I am a King, and subjects, of whatever religion they may be, have an equal right to be protected. I am a King, but as the Pope himself told me, I am not an Apostle.” Yet, at the same time, James Francis Edward utterly refused to listen to any persuasion that he should change his own religion in order to become King more easily. (In 1701, the Act of Settlement sought to ensure a Protestant succession and to exclude his claim. Heirs to the throne must themselves be Protestants, and they must not marry Catholics.) In contrast, Charles Edward eventually became an Anglican for such opportunistic reasons. Surely, James Francis Edward revealed himself as the more principled man of the two. His greater strength of character showed, too, in his reaction to the failure of the Jacobite risings in which he himself took part. While after 1746 Bonnie Prince Charlie brooded over defeat and drank himself into a stupefied and miserable middle age, James Francis Edward after 1719 for the most part shelved any ideas about active campaigning and lived a new life in Italy. Born in St. James’s Palace in London, he had lived but a few weeks on his native soil before his parents’ 1688 exile led them to seek refuge with James II’s first cousin, Louis XIV of France. Louis had housed his cousins in St-Germain-en-Laye, twelve miles west of Paris and not far from Versailles. Although Louis recognized James Francis Edward as the rightful King of Great Britain in 1701, the Treaty of Utrecht (1713-1714) forced Louis to expel James Francis Edward from French soil. After the subsequent failure of the Fifteen, James Francis Edward wandered—to Lorraine, to Avignon (then papal territory), to various places in Italy, then finally to Rome and Urbino. A sympathetic Pope Clement XI gave the exile a pension and allowed him to live in Palazzo Muti in Rome, near Santi Apostoli. Clement also lent Palazzo Savelli at Albano as a summer home. By accepting refuge in Rome, James Francis Edward effectively surrendered any hope of gaining the Protestant support vital to his restoration. After 1719, he still claimed to rule as “James III” and indulged in some intrigue but essentially made another life for himself for the next 45 years. The scene had shifted to Rome internally as well as externally. His marriage in 1719 to Princess Clementina of Poland, granddaughter of John III Sobieski and goddaughter of Clement XI, produced two sons: Charles Edward, born in 1720, and Henry Benedict, born in 1725. So uninterested was James Francis Edward in further Jacobite risings that Charles Edward told him of the Forty-five in a letter written on the day Charles Edward sailed for Scotland. James Francis Edward reacted with dismay, “Heaven forbid that all the crowns of the world should rob me of my son.”

James Francis Edward felt compelled to assert his right as Prince of Wales to the British throne stolen from his father and made many plans that finally culminated in his three campaigns of 1708, 1715, and 1719. His own withdrawn personality and frequent malarial illnesses proved detrimental to military success. Nicknamed “Old Mr. Melancholy” or "Old Mr. Misfortune" by English satirists, James Francis Edward seemed lethargic, depressed, and uninspiring to his followers in Scotland. As one Jacobite Scot recorded, “we found ourselves not at all animated by his presence; if he was disappointed in us, we were tenfold more so in him. We saw nothing in him that looked like spirit. . . . Some said the circumstances he found us in dejected him; I am sure the figure he made dejected us.” In 1745, the far more athletic and extroverted Bonnie Prince Charlie would spark a very different reaction. Yet, while Charles Edward proved himself the better leader of men at arms, James Francis Edward would have made the better King and was the better man. The conscientiousness that drove James Francis Edward to assert his father’s right would have driven him also to rule well. In addition, he had none of the religious bigotry that had hardened James II’s subjects against him. In fact, the dying James II advised James Francis Edward to establish liberty of conscience upon his restoration. James Francis Edward himself wrote, “I am a Catholic, but I am a King, and subjects, of whatever religion they may be, have an equal right to be protected. I am a King, but as the Pope himself told me, I am not an Apostle.” Yet, at the same time, James Francis Edward utterly refused to listen to any persuasion that he should change his own religion in order to become King more easily. (In 1701, the Act of Settlement sought to ensure a Protestant succession and to exclude his claim. Heirs to the throne must themselves be Protestants, and they must not marry Catholics.) In contrast, Charles Edward eventually became an Anglican for such opportunistic reasons. Surely, James Francis Edward revealed himself as the more principled man of the two. His greater strength of character showed, too, in his reaction to the failure of the Jacobite risings in which he himself took part. While after 1746 Bonnie Prince Charlie brooded over defeat and drank himself into a stupefied and miserable middle age, James Francis Edward after 1719 for the most part shelved any ideas about active campaigning and lived a new life in Italy. Born in St. James’s Palace in London, he had lived but a few weeks on his native soil before his parents’ 1688 exile led them to seek refuge with James II’s first cousin, Louis XIV of France. Louis had housed his cousins in St-Germain-en-Laye, twelve miles west of Paris and not far from Versailles. Although Louis recognized James Francis Edward as the rightful King of Great Britain in 1701, the Treaty of Utrecht (1713-1714) forced Louis to expel James Francis Edward from French soil. After the subsequent failure of the Fifteen, James Francis Edward wandered—to Lorraine, to Avignon (then papal territory), to various places in Italy, then finally to Rome and Urbino. A sympathetic Pope Clement XI gave the exile a pension and allowed him to live in Palazzo Muti in Rome, near Santi Apostoli. Clement also lent Palazzo Savelli at Albano as a summer home. By accepting refuge in Rome, James Francis Edward effectively surrendered any hope of gaining the Protestant support vital to his restoration. After 1719, he still claimed to rule as “James III” and indulged in some intrigue but essentially made another life for himself for the next 45 years. The scene had shifted to Rome internally as well as externally. His marriage in 1719 to Princess Clementina of Poland, granddaughter of John III Sobieski and goddaughter of Clement XI, produced two sons: Charles Edward, born in 1720, and Henry Benedict, born in 1725. So uninterested was James Francis Edward in further Jacobite risings that Charles Edward told him of the Forty-five in a letter written on the day Charles Edward sailed for Scotland. James Francis Edward reacted with dismay, “Heaven forbid that all the crowns of the world should rob me of my son.”  After the disaster of the Forty-five, James Francis Edward showed again how little he thought of Jacobite aspirations when in 1747 he supported his son Henry’s being made a Cardinal of the Catholic Church. Alive to the political consequences of this event, enraged by what he saw as his father’s and brother’s betrayal of the Jacobite cause, Charles Edward never saw James Francis Edward again. While Charles Edward wrote to his father from time to time, he maintained a total estrangement from his brother Henry for 18 years. Henry re-established contact with Charles Edward as their aging father declined, but Charles Edward refused to visit until Pope Clement XIII recognized his rights to the throne as James Francis Edward’s heir. James Francis Edward died in 1766 as Charles Edward preserved a stubborn absence that had lasted 22 years. After honorably asserting his claim, James Francis Edward sensibly recognized the futility of further assertion. And yet, sensible as his turning away from Jacobitism seems, the romance of his being the “Chevalier de Saint George” or “the King over the Water” still lingers. The rising of 1708 acted against James Francis Edward’s half-sister Queen Anne, who had succeeded William and Mary. Angered by his action into terming James Francis Edward “the Pretender,” Anne nevertheless sought to give the impression at times that she preferred her half-brother to any other successor, especially the detested Hanoverians specified by the 1701 Act of Settlement.

After the disaster of the Forty-five, James Francis Edward showed again how little he thought of Jacobite aspirations when in 1747 he supported his son Henry’s being made a Cardinal of the Catholic Church. Alive to the political consequences of this event, enraged by what he saw as his father’s and brother’s betrayal of the Jacobite cause, Charles Edward never saw James Francis Edward again. While Charles Edward wrote to his father from time to time, he maintained a total estrangement from his brother Henry for 18 years. Henry re-established contact with Charles Edward as their aging father declined, but Charles Edward refused to visit until Pope Clement XIII recognized his rights to the throne as James Francis Edward’s heir. James Francis Edward died in 1766 as Charles Edward preserved a stubborn absence that had lasted 22 years. After honorably asserting his claim, James Francis Edward sensibly recognized the futility of further assertion. And yet, sensible as his turning away from Jacobitism seems, the romance of his being the “Chevalier de Saint George” or “the King over the Water” still lingers. The rising of 1708 acted against James Francis Edward’s half-sister Queen Anne, who had succeeded William and Mary. Angered by his action into terming James Francis Edward “the Pretender,” Anne nevertheless sought to give the impression at times that she preferred her half-brother to any other successor, especially the detested Hanoverians specified by the 1701 Act of Settlement.  As Anne’s health declined a few years later, the Jacobite James Douglas, 4th Duke of Hamilton, wanted James Francis Edward in Scotland to await the Queen’s death. James Fitzjames, 1st Duke of Berwick (a bastard of James II by Arabella Churchill), planned to have James Francis Edward meet their half-sister Queen Anne in London. Hamilton’s suspicious death in a duel aborted such plans, and the throne passed to the Hanoverian descendants of Elizabeth of Bohemia. The risings of 1715 and 1719 (against George I), and of 1745 (against George II) failed to dislodge them. With Hamilton’s death in 1712 and Anne’s death in 1714, the opportunity for reconciliation and restoration had died as well. A brilliant rendering of Jacobite intrigue complete with an unflattering, unfair, and unforgettable view of James Francis Edward, Thackeray’s historical novel Henry Esmond portrays this lost moment—and all the Jacobite strivings—in all their comedy, tragedy, romance, and futility.

As Anne’s health declined a few years later, the Jacobite James Douglas, 4th Duke of Hamilton, wanted James Francis Edward in Scotland to await the Queen’s death. James Fitzjames, 1st Duke of Berwick (a bastard of James II by Arabella Churchill), planned to have James Francis Edward meet their half-sister Queen Anne in London. Hamilton’s suspicious death in a duel aborted such plans, and the throne passed to the Hanoverian descendants of Elizabeth of Bohemia. The risings of 1715 and 1719 (against George I), and of 1745 (against George II) failed to dislodge them. With Hamilton’s death in 1712 and Anne’s death in 1714, the opportunity for reconciliation and restoration had died as well. A brilliant rendering of Jacobite intrigue complete with an unflattering, unfair, and unforgettable view of James Francis Edward, Thackeray’s historical novel Henry Esmond portrays this lost moment—and all the Jacobite strivings—in all their comedy, tragedy, romance, and futility.

Part Two:

For who better may Our high scepter sway, Than he whose right it is to reign: Then look for no peace, For the wars will never cease Till the King shall enjoy his own again.So sang Bonnie Prince Charlie to Flora Macdonald during their flight together after the disastrous Jacobite defeat at Culloden in 1746. First sung in reference to the imprisoned and executed Charles I and his successor in exile, Charles II, “The King Shall Enjoy His Own Again” later became a Jacobite song. It heartened the supporters of the expelled James II, his son James Francis Edward, “the Old Pretender” or “the Chevalier de Saint George,” and his grandson Charles Edward, “the Young Pretender” or “the Young Chevalier.” In 1746, Charles Edward defiantly sang it after the final defeat of Jacobite hopes. Those hopes had always depended on the lucky conjunction of foreign diplomatic, military, and financial support with British discontent and competent generalship. In 1689-90, 1708, 1715, and 1719, James II and then James Francis Edward had found that conjunction unstable. In the third phase of Jacobite rebellion, this time led in 1745-46 by Charles Edward, equivocal foreign aid, unreliable English support, and questionable military decisions doomed Bonnie Prince Charlie’s attempt to gain Britain for his father and to rule there himself as Regent. Though smashed by the Hanoverians at Culloden and disillusioned about European recognition of his claim, Charles Edward never accepted the defeat of Jacobite hopes. His father and his younger brother, Henry Benedict, more realistically knew that Culloden had rung the death knell. Charles’s obstinately clinging to the dream of a Jacobite restoration, and Henry’s realizing its inherent impracticality set the brothers on very different—indeed, diametrically opposed—paths. While Charles insisted on being a Prince of Great Britain, Henry settled for being a Prince of the Church—by choosing in 1747 the path that led to his becoming a Roman Catholic Cardinal. Divided in life by these choices, the brothers are buried together with their father James Francis Edward in the crypt of St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican beneath the Monument to the Stuart Kings commissioned by Pope Pius VII, sculpted by Canova, and paid for by George IV. (George VI and his Queen Elizabeth in 1939 had a sarcophagus built over the three tombs.) The grave of the mother of Charles and Henry, James Francis Edward’s wife Clementina, also lies in St. Peter’s, behind the Monument to Queen Clementina. Finally united in death, the members of this fractious family seldom were united during their lives.

Granddaughter of the Polish King John III Sobieski and goddaughter of Pope Clement XI, the 17-year-old Clementina married James Francis Edward in 1719. Doing a favor for George I, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI had sought to prevent the marriage by arresting Clementina at Innsbruck; from there, she made a daring escape with the help of James Francis Edward’s supporters and then married him by proxy in Bologna. She gave birth to Charles Edward in 1720 and to Henry Benedict in 1725. During these early years of the family’s long sojourn in Palazzo Muti in Rome, husband’s and wife’s initial delight in each other soured with familiarity. A power struggle evolved over the Protestant members of James Francis Edward’s household. Although the Pope scolded Clementina for her intolerance, she feared their influence over her sons. Failing to sway her husband, Clementina ran away to the Ursuline convent at Santa Cecilia in Trastevere. James Francis Edward lost financial and political support because his alleged but unlikely adultery supposedly provoked her flight. Clementina stubbornly stayed in her convent for many months until the Pope told her she might be forbidden the sacraments unless she returned to her husband. In 1727, she finally complied, but a much-changed woman now lived in Palazzo Muti. She had become extremely devout, compulsive in her religious observances, and so stringent in her fasting that she ate alongside the family at a small table holding scanty portions of specially prepared meals. An emaciated 33-year old Clementina died in 1735. Perhaps anorexia served as a defiant, if self-destructive, response to her perceived powerlessness in her household and contributed largely to her death.

Granddaughter of the Polish King John III Sobieski and goddaughter of Pope Clement XI, the 17-year-old Clementina married James Francis Edward in 1719. Doing a favor for George I, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI had sought to prevent the marriage by arresting Clementina at Innsbruck; from there, she made a daring escape with the help of James Francis Edward’s supporters and then married him by proxy in Bologna. She gave birth to Charles Edward in 1720 and to Henry Benedict in 1725. During these early years of the family’s long sojourn in Palazzo Muti in Rome, husband’s and wife’s initial delight in each other soured with familiarity. A power struggle evolved over the Protestant members of James Francis Edward’s household. Although the Pope scolded Clementina for her intolerance, she feared their influence over her sons. Failing to sway her husband, Clementina ran away to the Ursuline convent at Santa Cecilia in Trastevere. James Francis Edward lost financial and political support because his alleged but unlikely adultery supposedly provoked her flight. Clementina stubbornly stayed in her convent for many months until the Pope told her she might be forbidden the sacraments unless she returned to her husband. In 1727, she finally complied, but a much-changed woman now lived in Palazzo Muti. She had become extremely devout, compulsive in her religious observances, and so stringent in her fasting that she ate alongside the family at a small table holding scanty portions of specially prepared meals. An emaciated 33-year old Clementina died in 1735. Perhaps anorexia served as a defiant, if self-destructive, response to her perceived powerlessness in her household and contributed largely to her death.  Charles supposedly resembled his mother in temperament, while Henry resembled their father. As the boys grew to manhood without their mother, the athletic Charles trained himself to lead a Jacobite rebellion by hunting, shooting, hiking in bare feet, and reading military manuals. Early in his own life, Henry became extremely observant of his religion, just as their father became after Clementina’s death. The European political situation seemed to offer Charles an opening. France sought a way to hamper George II from helping Austria during the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48). A Jacobite rising in Scotland might serve as an effective means. Promises of French support proved equivocal, however, and James Francis Edward distrusted them out of long experience. Determined to go ahead even without French support, Charles announced his embarking for Scotland in a letter written to his father on the very day he gallantly landed with a tiny force in the Hebrides, on the island of Eriskay, at a place later called “the Prince’s Strand.” With charm, courage, gallantry, and persuasiveness—by sheer force of personality—he stirred the reluctant Highlanders not only to recognize his claim but also to fight for it. Later the Jacobite Lord Balmerino at his own execution testified about Charles: “the incomparable sweetness of his nature, his affability, his compassion, his justice, his temperance, his patience, and his courage are virtues, seldom to be found in one person.” Resentful of the 1707 Union with England that had ended Scotland’s status as a discrete nation with its own Parliament, the clan chiefs sought to restore the Stuarts to a Scottish throne and to achieve Scottish independence. Charles succeeded with the Highlanders’ help in mastering Scotland, but his desire to invade England met with Highlander misgivings and resistance. Eventually, his officers argued for a retreat to Scotland, where William Augustus, the Duke of Cumberland and the son of George II, routed Charles’s troops at Culloden Moor in April, 1746. A hunted fugitive until he escaped to France in September, 1746, Charles received much help from such supporters as Flora Macdonald during his perilous journey to safety.

Charles supposedly resembled his mother in temperament, while Henry resembled their father. As the boys grew to manhood without their mother, the athletic Charles trained himself to lead a Jacobite rebellion by hunting, shooting, hiking in bare feet, and reading military manuals. Early in his own life, Henry became extremely observant of his religion, just as their father became after Clementina’s death. The European political situation seemed to offer Charles an opening. France sought a way to hamper George II from helping Austria during the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48). A Jacobite rising in Scotland might serve as an effective means. Promises of French support proved equivocal, however, and James Francis Edward distrusted them out of long experience. Determined to go ahead even without French support, Charles announced his embarking for Scotland in a letter written to his father on the very day he gallantly landed with a tiny force in the Hebrides, on the island of Eriskay, at a place later called “the Prince’s Strand.” With charm, courage, gallantry, and persuasiveness—by sheer force of personality—he stirred the reluctant Highlanders not only to recognize his claim but also to fight for it. Later the Jacobite Lord Balmerino at his own execution testified about Charles: “the incomparable sweetness of his nature, his affability, his compassion, his justice, his temperance, his patience, and his courage are virtues, seldom to be found in one person.” Resentful of the 1707 Union with England that had ended Scotland’s status as a discrete nation with its own Parliament, the clan chiefs sought to restore the Stuarts to a Scottish throne and to achieve Scottish independence. Charles succeeded with the Highlanders’ help in mastering Scotland, but his desire to invade England met with Highlander misgivings and resistance. Eventually, his officers argued for a retreat to Scotland, where William Augustus, the Duke of Cumberland and the son of George II, routed Charles’s troops at Culloden Moor in April, 1746. A hunted fugitive until he escaped to France in September, 1746, Charles received much help from such supporters as Flora Macdonald during his perilous journey to safety.  In France, Charles found that defeat increased equivocation exponentially. Henry (and their father) understood that Jacobite hopes had died at Culloden, but Charles obstinately insisted on living as though those hopes were realizable. He refused to leave France after the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle specified that Pretenders to the British throne could not reside in Britain, France, Holland, Germany, Spain, or Genoa; Louis XV had to expel Charles by force. After a stay in papal Avignon, Charles went underground for almost 20 years. Wandering through Europe in disguise, he even made secret visits to England in 1750 and later. In London in 1750, he became an Anglican, probably out of political calculation. Henry heard nothing from Charles and James Francis Edward very little, because Charles had felt enraged by Henry’s becoming a Cardinal in 1747. Although at that time Cardinals need not be priests, Henry chose ordination in 1748. His ecclesiastical career proceeded as he became a Cardinal-Priest in 1752; the Camerlengo in charge of the papal conclave in 1758; Cardinal-Bishop with a see in Frascati in 1761; and Vice-Chancellor of the Church in 1763. Before abolishing the Jesuit order in 1773, Pope Clement XIV put Henry in charge of the Jesuit seminary at Frascati and made him an investigator of the Jesuit seminary in Rome.

In France, Charles found that defeat increased equivocation exponentially. Henry (and their father) understood that Jacobite hopes had died at Culloden, but Charles obstinately insisted on living as though those hopes were realizable. He refused to leave France after the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle specified that Pretenders to the British throne could not reside in Britain, France, Holland, Germany, Spain, or Genoa; Louis XV had to expel Charles by force. After a stay in papal Avignon, Charles went underground for almost 20 years. Wandering through Europe in disguise, he even made secret visits to England in 1750 and later. In London in 1750, he became an Anglican, probably out of political calculation. Henry heard nothing from Charles and James Francis Edward very little, because Charles had felt enraged by Henry’s becoming a Cardinal in 1747. Although at that time Cardinals need not be priests, Henry chose ordination in 1748. His ecclesiastical career proceeded as he became a Cardinal-Priest in 1752; the Camerlengo in charge of the papal conclave in 1758; Cardinal-Bishop with a see in Frascati in 1761; and Vice-Chancellor of the Church in 1763. Before abolishing the Jesuit order in 1773, Pope Clement XIV put Henry in charge of the Jesuit seminary at Frascati and made him an investigator of the Jesuit seminary in Rome.  Addressed as “Your Royal Highness and Eminence,” the Cardinal Duke of York made his home at the Palace of LaRocca in Frascati, with a summer home at Villa Muti outside Frascati. After he became Vice-Chancellor, he lived at Palazzo Cancelleria when in Rome. His large income derived from ecclesiastical offices in Flanders, Spain, Naples, France, and Spanish America, especially Mexico, where he owned land. Henry supported many Jacobites and eased the plight of Frascati’s poor. Nicholas Cardinal Wiseman, Archbishop of Westminster, later remarked of Henry, “to a royal heart he was no pretender. His charities were without bounds: poverty and distress were unknown in his see.”

Addressed as “Your Royal Highness and Eminence,” the Cardinal Duke of York made his home at the Palace of LaRocca in Frascati, with a summer home at Villa Muti outside Frascati. After he became Vice-Chancellor, he lived at Palazzo Cancelleria when in Rome. His large income derived from ecclesiastical offices in Flanders, Spain, Naples, France, and Spanish America, especially Mexico, where he owned land. Henry supported many Jacobites and eased the plight of Frascati’s poor. Nicholas Cardinal Wiseman, Archbishop of Westminster, later remarked of Henry, “to a royal heart he was no pretender. His charities were without bounds: poverty and distress were unknown in his see.”  Realizing the impracticality of a Jacobite restoration, Henry had entered upon a notably successful ecclesiastical career, while his brother, a determined Jacobite to the end, wandered through Europe in disguise. Their aging father, to whom Charles wrote occasionally, served as a tenuous link between the severed brothers. In 1765, Henry notified Charles of James Francis Edward’s decline and approaching death, but Charles refused to visit until the Pope recognized Charles’s royal claims. The father died without seeing again his prodigal son, and Charles returned in 1766 to live in Palazzo Muti in Rome. Although he now assumed the name of “Charles III,” he received little official recognition of his title and reluctantly accepted being called “Count of Albany.” (“Albany” was the traditional title of the second son of the King of Scotland.) Henry gave Charles Henry’s rights to their father’s papal pension. Although their father’s death had reunited the brothers, many crises strained their relationship. During his wandering years, Charles had lived with Clementina Walkinshaw, who had given birth to his daughter Charlotte. In 1760, Clementina ran away from Charles and took their daughter with her. “You pushed me to the greatest extremity, and even despair,” she wrote to him, “as I was always in perpetual dread of my life from your violent passions.”

Realizing the impracticality of a Jacobite restoration, Henry had entered upon a notably successful ecclesiastical career, while his brother, a determined Jacobite to the end, wandered through Europe in disguise. Their aging father, to whom Charles wrote occasionally, served as a tenuous link between the severed brothers. In 1765, Henry notified Charles of James Francis Edward’s decline and approaching death, but Charles refused to visit until the Pope recognized Charles’s royal claims. The father died without seeing again his prodigal son, and Charles returned in 1766 to live in Palazzo Muti in Rome. Although he now assumed the name of “Charles III,” he received little official recognition of his title and reluctantly accepted being called “Count of Albany.” (“Albany” was the traditional title of the second son of the King of Scotland.) Henry gave Charles Henry’s rights to their father’s papal pension. Although their father’s death had reunited the brothers, many crises strained their relationship. During his wandering years, Charles had lived with Clementina Walkinshaw, who had given birth to his daughter Charlotte. In 1760, Clementina ran away from Charles and took their daughter with her. “You pushed me to the greatest extremity, and even despair,” she wrote to him, “as I was always in perpetual dread of my life from your violent passions.”  James Francis Edward, and later Henry, supported mother and daughter because Charles would not do so. In 1772, Charles married Louise of Stolberg-Gedern, granddaughter of a Prince of the Holy Roman Empire. The marriage quickly deteriorated while they lived in Palazzo Guadigni in Florence; as an English observer commented in 1779, “she has paid dearly for the dregs of royalty.” As jealous of Louise as he had been of Clementina, Charles reverted to his pattern of physical abuse in a drunken rage on St. Andrew’s Day in 1780. He apparently also raped his wife because he suspected her of adultery with the Italian poet Count Vittorio Alfieri, whose muse Louise had been.

James Francis Edward, and later Henry, supported mother and daughter because Charles would not do so. In 1772, Charles married Louise of Stolberg-Gedern, granddaughter of a Prince of the Holy Roman Empire. The marriage quickly deteriorated while they lived in Palazzo Guadigni in Florence; as an English observer commented in 1779, “she has paid dearly for the dregs of royalty.” As jealous of Louise as he had been of Clementina, Charles reverted to his pattern of physical abuse in a drunken rage on St. Andrew’s Day in 1780. He apparently also raped his wife because he suspected her of adultery with the Italian poet Count Vittorio Alfieri, whose muse Louise had been.  In a reprise of the events of 55 years before, Louise ran away to the Convent of the White Nuns in Florence, and she turned the Pope and Henry against Charles. Henry even arranged for her to stay in Rome in the same Ursuline convent where his mother had sought refuge, but Louise eventually preferred to live in Palazzo Cancelleria. Henry did not become fully reconciled to Charles until after Charles in 1784 legitimized his daughter Charlotte, named her Duchess of Albany, and asked her to care for him in his decrepit middle age. Having developed a habit of drinking six bottles of Cyprus wine after dinner, Charles obviously needed a caretaker. To her credit, Charlotte took good care of her previously neglectful father, though he tried her patience. She exasperatedly noted that he resembled a fifteen-year-old boy.

In a reprise of the events of 55 years before, Louise ran away to the Convent of the White Nuns in Florence, and she turned the Pope and Henry against Charles. Henry even arranged for her to stay in Rome in the same Ursuline convent where his mother had sought refuge, but Louise eventually preferred to live in Palazzo Cancelleria. Henry did not become fully reconciled to Charles until after Charles in 1784 legitimized his daughter Charlotte, named her Duchess of Albany, and asked her to care for him in his decrepit middle age. Having developed a habit of drinking six bottles of Cyprus wine after dinner, Charles obviously needed a caretaker. To her credit, Charlotte took good care of her previously neglectful father, though he tried her patience. She exasperatedly noted that he resembled a fifteen-year-old boy.  Charlotte also effected a reconciliation of Charles with Henry. Charles returned to Rome in 1785 to live once again in Palazzo Muti, this time with Charlotte. When he had lived there with Louise before they moved to Florence, the Romans had called her their “Queen of Hearts.” Three years later, after Charles died, Henry, tears streaming down his face, conducted a private royal burial in Frascati. (The public royal funeral held for James Francis Edward was not permitted for Charles.) He sent a Memorial to foreign courts asserting his claim to be Henry IX and the right of his named successor Charles Emmanuel IV, King of Sardinia (a descendant of Henrietta Stuart, sister of James II). Other than honorably keeping faith with his dead by asserting their and his claim, Henry made no move to effect a Jacobite restoration after forty years’ realization of its futility. The 1796 Napoleonic invasion of Italy, with its threat to the Papacy, caused the Cardinal King to donate much of his fortune to preserve the Holy See. Two years later, the fortunes of war caused Henry to flee from his beloved Frascati to Naples, then to Sicily, then to Venice in order to hold a conclave to elect a successor to Pope Pius VI. In the meantime, Henry’s wealth had vanished. His friends sent an appeal to Prime Minister William Pitt, who informed George III. Henry’s Hanoverian cousin sent immediate financial relief and instituted a pension for life in 1800. (Pitt probably never told George III that the British government actually owed over ₤1 million to this heir of James II's Queen Mary of Modena.) The Cardinal King appreciated this kindness (as well as the friendly and gracious encounters he had had with George III’s son, Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex, who insisted on addressing the Cardinal as "Your Royal Highness," a courtesy reciprocated by Henry). In his will, he left to the Prince of Wales (later George IV) the British crown jewels carried by James II and Queen Mary Beatrice in their 1688 flight from England.

Charlotte also effected a reconciliation of Charles with Henry. Charles returned to Rome in 1785 to live once again in Palazzo Muti, this time with Charlotte. When he had lived there with Louise before they moved to Florence, the Romans had called her their “Queen of Hearts.” Three years later, after Charles died, Henry, tears streaming down his face, conducted a private royal burial in Frascati. (The public royal funeral held for James Francis Edward was not permitted for Charles.) He sent a Memorial to foreign courts asserting his claim to be Henry IX and the right of his named successor Charles Emmanuel IV, King of Sardinia (a descendant of Henrietta Stuart, sister of James II). Other than honorably keeping faith with his dead by asserting their and his claim, Henry made no move to effect a Jacobite restoration after forty years’ realization of its futility. The 1796 Napoleonic invasion of Italy, with its threat to the Papacy, caused the Cardinal King to donate much of his fortune to preserve the Holy See. Two years later, the fortunes of war caused Henry to flee from his beloved Frascati to Naples, then to Sicily, then to Venice in order to hold a conclave to elect a successor to Pope Pius VI. In the meantime, Henry’s wealth had vanished. His friends sent an appeal to Prime Minister William Pitt, who informed George III. Henry’s Hanoverian cousin sent immediate financial relief and instituted a pension for life in 1800. (Pitt probably never told George III that the British government actually owed over ₤1 million to this heir of James II's Queen Mary of Modena.) The Cardinal King appreciated this kindness (as well as the friendly and gracious encounters he had had with George III’s son, Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex, who insisted on addressing the Cardinal as "Your Royal Highness," a courtesy reciprocated by Henry). In his will, he left to the Prince of Wales (later George IV) the British crown jewels carried by James II and Queen Mary Beatrice in their 1688 flight from England.  Henry’s 1802 will also left his claim to the King of Sardinia (of the House of Savoy), the claim eventually by a tangled chain being passed to the Dukes of Bavaria. In 1803, as the most senior Cardinal, the Cardinal King became Dean of the College of Cardinals. Four years later, he died on the 46th anniversary of his being made Bishop of Frascati. While Charles had spoiled more than 40 years by making undignified attempts to preserve his royal dignity, Henry merely called himself King non desideriis hominum sed voluntate Dei—“not by the desire of man but by the will of God.” Endearingly, Henry did insist, however, that the stray King Charles spaniel that glued itself to him one day at St. Peter’s had instinctively recognized him as a royal Stuart.

Henry’s 1802 will also left his claim to the King of Sardinia (of the House of Savoy), the claim eventually by a tangled chain being passed to the Dukes of Bavaria. In 1803, as the most senior Cardinal, the Cardinal King became Dean of the College of Cardinals. Four years later, he died on the 46th anniversary of his being made Bishop of Frascati. While Charles had spoiled more than 40 years by making undignified attempts to preserve his royal dignity, Henry merely called himself King non desideriis hominum sed voluntate Dei—“not by the desire of man but by the will of God.” Endearingly, Henry did insist, however, that the stray King Charles spaniel that glued itself to him one day at St. Peter’s had instinctively recognized him as a royal Stuart.

Will ye no come back again? Will ye no come back again? Better loed ye canna be; Will ye no come back again? Ye trusted in your Hielan men, They trusted you dear Charlie! They kent your hiding in the glen, Death and exile braving. English bribes were a in vain Tho puir and puirer we mun be; Siller canna buy the heart That aye beats warm for thine an thee.