Rural England in the Age of Jane Austen

by Marc DeSantis

A Rural England

Though Jane Austen’s life of forty-one years was lamentably short, her time on earth, 1775 to 1817, was nonetheless one of great and momentous change. England was still largely rural in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and the rhythm of its country life was tied to the seasonal needs of agriculture. The population of Britain at the dawn of the nineteenth century was nine million, with four-fifths of this total living in the country. Fully one-third of the population of England was employed in agriculture. Like farmers in all times and places, the rural folk of Jane’s English countryside were at the mercy of the weather, which was especially fickle in the late eighteenth century. The winters were often very cold, and the springs very wet and late in arriving. Summers could be either very dry or cold and wet. Crops and livestock could be devastated by too much cold or not enough rain. Poor weather also encouraged the spread of blights and rots. When the wheat harvest was bad, the price of bread shot up, making it hard for the poor to feed themselves, and riots over food would sometimes erupt among the rural hungry. Life in the country had other hardships. There were highwaymen on the roads ready to waylay travelers, groups of gypsies robbed countryfolk as well, and thieves stole horses and other valuables.

On some occasions there were even murders, particularly when it was thought that a vulnerable mark might have some money on him. Gas and electrical lighting still lay in the future. Illumination was provided by candles, with the finest being made from beeswax, which burned with minimal smoke. Ordinary candles were of tallow, made from animal fat. Though cheaper, they were not as bright and their smell was less than ideal. For the heating of homes, coal was increasing in use thanks to Britain’s developing network of canals, which made transporting the fuel much easier. Wood was of course still in widespread use, especially where it could be had more cheaply than coal. Though collecting firewood was a time-consuming activity, particularly for the poor, working in the mines digging coal out was even less appealing work. The hazard of lethal explosions deep underground was constant. Many other miners lost their lives when the roofs of their tunnels caved in or to other mishaps.

Festivities

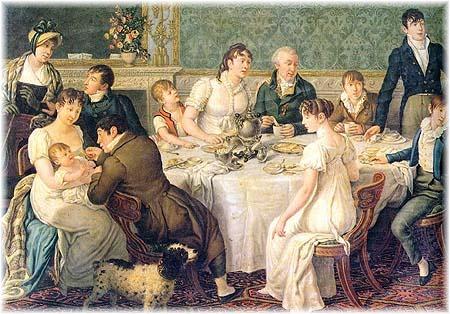

Yet country living was not without its charms and pleasures. The boring toil of agricultural work was broken by seasonal festivals such as May Day. Towns had markets which provided a venue in which country people could sell their food, including such edibles as poultry, eggs, and vegetables. If these markets outgrew their original surroundings, then fairs were held outside the towns in nearby fields. The fairs became ever larger when merchants selling tools, cheese, clothing, earthenware, and leather goods arrived. With so many people present, other vendors began to sell food and drink to the visitors. Sports and other games were also part of the festivities, with the fair becoming something far greater than its original purpose of being a place to sell farm produce. Dancing was also included in a fair’s usual list of activities, and was a popular form of entertainment everywhere.

For a young middle-class woman such as Jane, residing in the country, dancing was a premier delight. It was on the dance floor where she could meet people and make friends. The countryside was not disconnected from the wider world. When word reached the inhabitants of great victories won against England’s enemies, celebrations would erupt, which included parades, music, and fireworks. Jane’s own brothers, Francis and James, were serving with the Royal Navy during the long wars with France, and each would rise to the rank of admiral. Jane, along with her family, would spend the years 1806-1809 in Southampton to be close to the great navy base of Portsmouth where her brothers served.

War Abroad, Taxes at Home

Britain was to be at war for most of Jane’s life, first with her rebellious colonies in America, and then with France from 1793 to 1815 during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. This produced enormous demand for food which could only be met in the country, which was intensively farmed. Not a single bit of arable land was allowed to go to waste.

The pressing need for money to pay for Britain’s army and navy also saw the levying of many unpopular taxes, including the introduction in 1799 of the much detested “Income Tax” of up to two shillings per pound (there were twenty shillings in a pound sterling). This imposition was only repealed in 1815, when the era of the great wars came to a close. Money was sometimes a problem in another way. “Real” money in Jane’s day was still of gold or silver, and paper bank notes were often refused as tender when metal money was in short supply. When there was not enough metallic currency to go around ordinary life and business could not be conducted. This caused great anxiety when people found themselves short of coins and were left wondering how they were going to pay for anything.

The Regency

Britain underwent important political and cultural changes during Jane’s lifetime. She would know only one king, George III, who would reign for nearly sixty years. However, the king was beset by bouts of severe mental illness, with the last and most serious one arriving in 1810. He was found to be incapable of carrying on his duties as monarch, and Parliament passed the Regency Bill in 1811, which made his son, the roguish and high-living Prince of Wales, regent of the kingdom until the king died in 1820. It was said of the frivolous prince that he “was addicted to lying, tippling and low company.”

The Prince Regent also had an insatiable hunger for women and a startling propensity to land himself deep in debt. He would nevertheless eventually ascend the throne upon his father’s death and become George IV. These years came to be known as the Regency, an era deemed one of high achievement in art, architecture, music, and literature, but also of deep moral laxity. The loose-living of the Regency was in many ways a reaction to the strait-laced and dull propriety of George III’s reign. Not everyone shared the enthusiasms of England’s “Prince of Pleasure.” At the forefront of these were the Evangelicals, who looked askance at many of the common amusements of the day such as dancing, prize-fighting, and card games, believing them dangerous to one’s soul. Despite its often dour and puritanical outlook, Evangelical Christianity was a growing force for moral improvement around Britain, gaining strength from the need to correct the perceived immorality of the period and remedy the general harshness of life for the common people.

In contrast to the bad examples set by too many aristocrats, the Evangelicals preached discipline and personal responsibility. This humanitarian spirit also sought to turn the Christian religion into a force for social good, with one of the movement’s leading lights being the abolitionist William Wilberforce, who founded the Society for the Suppression of Vice in 1797. Wilberforce’s Practical Christianity was one of Evangelicalism’s principal guides to a more moral way of life, and overall the movement was not without success. The legal abolishment of the slave trade in 1807 is largely attributable to the efforts of the Evangelicals.

Toward a Middle Class Industrial Nation

Snobbery toward the prosperous middle class, growing in size and influence, was still very strong in Jane’s England. “[W]e are not absolutely a nation of shopkeepers,” one gentlemen’s magazine sniffed, but “[w]e are much afraid that nine-tenths of the middling . . . sort of people among ourselves belong to this reprobated class of traders and dealers, and have much the same manners with their brethren in America.”

But the future would ultimately belong to the middle class. Tectonic changes were coming to England’s economy far from the bucolic countryside that Jane knew, with merchants, factory owners, and inventors of the middle rank leading the way. Cities were swelling as they drew ever more people to them for the opportunity to find work. These were the years when Britain’s Industrial Revolution accelerated, with its multiplying factories consuming vast amounts of coal and producing ever-increasing amounts of iron and finished textiles made from cotton. Industrial production shot skyward, doubling in just the twenty years between 1780 and 1800.

The demand for labor and raw materials for the factories would only increase, and Britain was well on its way to becoming the world first industrialized nation. The increasing mechanization of work in the factories produced a backlash from disaffected workers known as Luddites. They would smash the new mechanical looms not, as is commonly thought, because they wanted to stop technological progress, but because the machines they attacked were turning out inferior stockings that flooded the marker and depressed prices even for better quality items. The basic dispute was not over technology but disgust that some employers were taking a shortcut to quick profits by knocking out substandard goods. Nonetheless, English justice was extremely harsh and unforgiving toward the Luddites.

After one 1813 trial in York, a dozen machine-smashers were hanged. The defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815 marked the end of the long wars with France. The Royal Navy was the unchallenged mistress of the seas, a preeminent position that it would hold for the rest of the nineteenth century. The Britain that Jane left behind when she passed away in 1817 was now the most powerful and economically advanced nation in the world, sitting at the hub of a large and expanding overseas empire.

Marc DeSantis is a historian and author in want of a wife. He lives in New York.

Enjoyed this article? If you don't want to miss a beat when it comes to Jane Austen, make sure you are signed up to the Jane Austen newsletter for exclusive updates and discounts from our Online Gift Shop.

5 comments

Excellent article !

Many thanks

Isnard

Loved the article, Marc! I’m not sure if you saw the post above mine, but there might be a Mrs. DeSantis in the offing. Anyone filling that role would never lack for interesting and stimulating company.

Alene Scoblete

James Austen was a clergyman. Francis and Charles were in the Navy.

Anonymous

It’s a very interesting article!

I would like to read any others like this one. And if he is looking for a wife….I’m here!

Anonymous

Wonderful article! Thanks.

May McGoldrick

Anonymous

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.