Mary Elizabeth (Williams) Lucy

Mary Elizabeth (Williams) Lucy was born November 25, 1803. Her life could have been drawn from an Austen novel-- a pampered younger daughter, as Austen herself was, number six of eight children, she was close to her siblings throughout her life and grew up in what she called "a cloudless childhood".

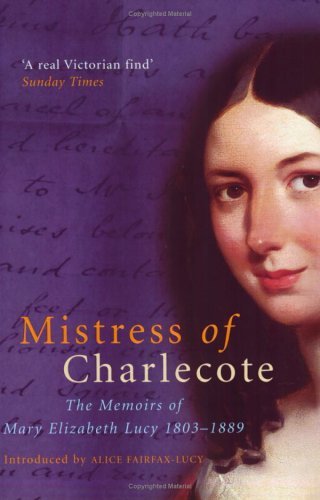

Mary Elizabeth (Williams) Lucy was born November 25, 1803. Her life could have been drawn from an Austen novel-- a pampered younger daughter, as Austen herself was, number six of eight children, she was close to her siblings throughout her life and grew up in what she called "a cloudless childhood". Reluctantly wed at age 20 to George Lucy of Charlecote Hall, Mary soon came to love her husband and home. Later in life she chose to write her memoirs as a way to pass the time and provide amusement for her grandchildren. Most of what we know about her life comes from this memoir and the resulting work could have been written by Elizabeth Bennet, Emma Woodhouse or a score of other heroines (all gentlemen's daughters) who married into the upper classes of the waning Regency.

When Mary married in 1823, her husband, several years older than herself, had already spent a good deal of time and money in improving his estate, an Elizabethan monolith which had fallen into disrepair over the years. The current house, now belonging to the National Trust, was extensively remodeled in Victorian times by Mary Lucy and is presented today as it was when she was the mistress of the house.

Here, the Lucy family history is brought vividly to life by the portraits of each generation; from Sir Thomas Lucy, the local magistrate who allegedly flogged the young William Shakespeare for poaching the Lucy family heard of fallow deer, to the family who lived in the house in the early 20th century. Visitors can see many of the rooms used by the servants. The scullery, kitchen, laundry and brewhouse all offer a view of life below stairs while the carriage-house, coach-house and tack room include the Lucy family's carriage collection and riding gear.

"In the 1950s Alice Fairfax Lucy, who was then virtually mistress of Charlecote Old Hall in Warwickshire under the wing of the National Trust, was chronicling the history of Charlecote and the Lucy family, who had lived there for over 600 years. She came across five black notebooks written by Mary Elizabeth Lucy in her 80s, and found them so interesting that she prepared them for publication. Although Mary had come to Charlecote as a reluctant bride in 1823, her mother had told her, 'Love WILL come when you know all of Mr Lucy's good qualities', and these memoirs, written so many years later with her grandchildren in mind, suggest that she did attain love and happiness.

Charlecote became her beloved home, and eight children were born to her. Five of these children died within her lifetime, causing great anguish, but her life as mistress of Charlecote continued. There are lively accounts of balls and outings, visits, matchmaking and gossip, and brief descriptions of many personages mostly within the landed aristocracy, all recounted with vigour and humour. Divine Providence, the Social Order and the Empire were all fixed poles in Mary's life, and she shows no excitement about the Age of Progress, the literary giants of the time (although Sir Walter Scott does make a brief appearance), or currents of political thought, even though her husband was an MP. She accepts completely and unthinkingly the way things were.

The memoirs make a fascinating sourcebook for anyone interested in the Victorian era. Much that would astonish us is taken for granted: a burglar who had broken into Charlecote and stolen some important valuables was sentenced to transportation for 15 years, and the lightness of the sentence surprised the prisoner, as indeed 'it did all in court more particularly myself'. A journey to Europe for a period of two years, with four small children and a baby, accompanied by five staff, now seems much more like an endurance test, as very early on the baby became ill and died, and another was born in Nancy a year later. First-hand accounts of aristocratic life written by women are rare, and this is a remarkable insight into the time, and enjoyable reading for its own sake."*

Mary's was a life of great happiness, for she grew to love her husband deeply. Her country home, her children, the London season and a tour abroad all brought joy and fulfilment. But her contentment was marred by tragedy as few of her many children survived her. Her words reveal a character of great strength and determination. High-spirited, discerning and delightfully free from prudishness, Mary Elizabeth Lucy draws pen-portraits of the people she met - Queen Victoria and Sir Walter Scott among them - and provides an authentic view of life in fashionable 19th-century society. The journals she left behind are filled with the minutiae of daily life; of the struggles a young girl finds in suddenly being mistress of a large household, of house parties and dinner parties and even a presentation at court and a tête-à-tête with George the IV.

George Lucy died young and his wife, like Queen victoria herself, whom she so much resembled in later years, lived nearly half her life as a widow. She observed radical changes in life, attended the Crystal Palace exhibition and before she died in 1889, saw as much change in her life as any person can well expect.

As Alice Lucy writes in the afterward, "There was nothing remarkable in a Victorian lady with a houseful of servants and time on her hands settling down at her desk by the fire to write her recollections. What surprises us is that she was an old woman in her eighties when she began to do this, recalling the events of her long life as freshly as if it had all happened yesterday, as if in fact it was still happening, for each stage of her life that she describes is charged with the feelings of that moment-- she feels it all again, the emotions of the child who fell out of the swing, the bride who fainted at the altar, and the bereaved mother. Such total recall must be rare, adn during my search through some 500 years of Lucy family papers, it was she alone who rose up, palpable, vivid and real--and wither her the age in which she lived."

*Kirkus reviews

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.