Robert Burns: Poet, Lyricist and Scottish National Figure

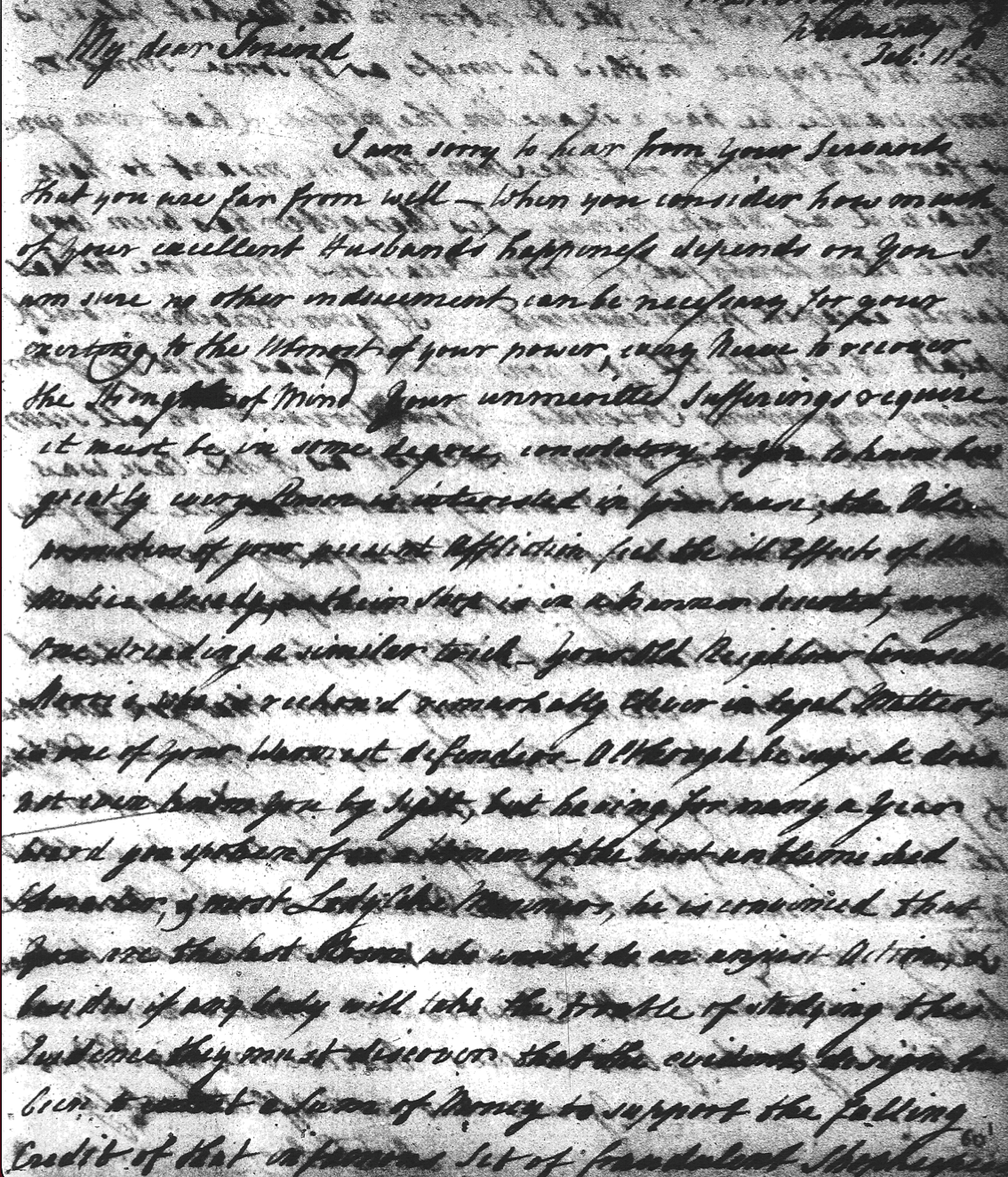

"I have read several of Burns' Poems with great delight", said Charlotte, as soon as she had time to speak, "but I am not poetic enough to separate a Man's Poetry entirely from his Character; -- & poor Burns' known Irregularities greatly interrupt my enjoyment of his Lines. -- I have difficulty in depending on the Truth of his Feelings as a Lover. I have not faith in the sincerity of the affections of a Man of his Description. He felt & he wrote & he forgot."

Sanditon, Jane Austen

Robert Burns (January 25, 1759 – July 21, 1796) was a poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and is the best-known poet to have written in the Scots language, although much of his writing is also in English and in a 'light' Scots dialect which would have been accessible to a wider audience. At various points in his career, Burns wrote pieces featuring political or civil commentary, and these are often examples of his most frank rhetoric. He is regarded as a pioneer of the Romantic movement and after his death became an important source of inspiration to the founders of both liberalism and socialism.

A cultural icon in Scotland and among Scots who have relocated to other parts of the world, his celebration became a charismatic craze during periods of the 19th and 20th centuries, and his influence has long since been strong on Scottish literature.

Burns, in addition to writing his poetry, collected folk songs from across Scotland and often revised or adapted them. His poem (and song) Auld Lang Syne is often sung at Hogmanay (New Year), and Scots Wha Hae served for a long time as an unofficial national anthem. Other poems and songs of his that remain well known today across the world include A Red, Red Rose, A Man's A Man for A' That, To a Louse, and To a Mouse. Burns Night, both in Scotland and around the world, is celebrated on the 25th of January with Burns' Suppers and is still more widely observed than the official national day, Saint Andrew's Day.

Burns is sometimes also referred to as 'Rabbie Burns', 'Scotland's favourite son', the 'Ploughman Poet', the 'Bard of Ayrshire', and in Scotland simply as 'The Bard'. He was born in Alloway, South Ayrshire and was the son of William Burnes (the poet originally spelt his surname Burness, but dropped the 'es'). His father was a farmer and a man of considerable force of character, whilst his mother Agnes Broun was the daughter of a tenant farmer from Kirkoswald, also in South Ayrshire.

Burns' youth was passed in poverty, hardship, and a degree of severe manual labour which left its traces in a premature stoop and weakened constitution. He had little regular schooling, and got much of what education he had from his father, who taught his children reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, and history, and also wrote for them A Manual of Christian Belief. He also received education from a tutor, John Murdock, who opened an 'adventure school' in the Alloway parish in 1763 and taught both Robert and his brother Gilbert Latin, French, and mathematics. With all his ability and character, however, the elder Burns was consistently unfortunate and migrated with his large family from farm to farm without ever being able to improve his circumstances.

In 1781 Burns went to Irvine to become a flax-dresser, but, as the result of a New Year carousal of the workmen, including himself, the shop took fire and was burned to the ground. This venture accordingly came to an end. In 1783 he started composing poetry in a traditional style using the Ayrshire dialect of Lowland Scots. In 1784 his father died, and Burns with his brother Gilbert made an ineffectual struggle to keep on the farm; failing in which they removed to Mossgiel, where they maintained an uphill fight for 4 years.

Burns was reputed to have an affinity for attractive young women of culture. One of his objects of affection was the young Eliza Burnett, daughter of Lord Monboddo. Burns' father was a tenant at the Monboddo House, and Robert was often a frequent visitor there at the learned suppers and as an excuse to see Eliza. He wrote several poems in honour of her beauty and grace, but Eliza sadly died at an early age and no serious consequence arose from their relationship. From 1783, there are at least four letters extant of Burns' writing to Eliza, all of which are romantic in content, one containing the passage: "without you I can never be happy". Burns wrote in 1786 of Eliza: "There has not been anything nearly like her in all the combinations of Beauty, Grace and Goodness the great Creator has formed, since Milton's Eve on the first day of her existence."

Meanwhile, his love affair with Jean Armour had passed through its first stage, and the troubles in connection therewith, combined with the want of success in farming, led him to think of going to Jamaica as a bookkeeper on a plantation. From this, he was dissuaded by a letter from Thomas Blacklock, and at the suggestion of his brother published his poems in the volume, Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish dialect in June 1786. This edition was bought out by a local printer in Kilmarnock and contained much of his best work, including The Twa Dogs, Address to the Deil, Hallowe'en, The Cottar's Saturday Night, To a Mouse, and To a Mountain Daisy, many of which had been written at Mossgiel.

The success of the work was immediate, the poet's name rang over all Scotland, and he was induced to go to Edinburgh to superintend the issue of a new edition. There he was received as an equal by the brilliant circle of men of letters which the city then boasted – Dugald Stewart, Robertson, Blair, etc., and was a guest at aristocratic tables, where he bore himself with unaffected dignity. Here also Walter Scott, then a boy of 15, saw him and describes him as of "manners rustic, not clownish. His countenance ... more massive than it looks in any of the portraits ... a strong expression of shrewdness in his lineaments; the eye alone indicated the poetical character and temperament. It was large, and of a dark cast, and literally glowed when he spoke with feeling or interest."

The results of this visit to Edinburgh included some life-long friendships, among which were those with Lord Glencairn and Mrs Dunlop. The new edition of his poetry brought him £400 and at about this time the episode of Highland Mary occurred. In the winter of 1786, Burns met James Johnson, a struggling music engraver and music seller, with a love of old Scots songs and a determination to preserve them. Burns shared this interest and became an enthusiastic contributor to The Scots Musical Museum. The first volume of this collection was published in 1787 and included three songs by Burns himself. He contributed 40 songs to the second volume and would end up responsible for roughly a third of the 600 songs in the whole collection. The final volume was published in 1803.

On his return to Ayrshire, he renewed his relations with Jean Armour, whom he ultimately married and took the farm of Ellisland near Dumfries. He took lessons in the duties of an exciseman as a line to fall back upon, should farming prove again unsuccessful. At Ellisland his society was cultivated by the local gentry and this, coupled with his interest in literature and his duties in the Customs and Excise (to which he had been appointed in 1789), proved too much of a distraction to admit success on the farm. In 1791, he gave up the farm and focused on his writing, which at this time was at its very best.

About this time Burns was offered and declined an appointment in London on the staff of the Star newspaper, and refused to become a candidate for a newly-created Chair of Agriculture in the University of Edinburgh, although influential friends offered to support his claims. After giving up his farm, Burns removed to nearby Dumfries and being requested to furnish words for The Melodies of Scotland, he responded by contributing an impressive over 100 songs. He made major contributions to George Thomson's A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs for the Voice as well as to James Johnson's The Scots Musical Museum. Arguably his claim to immortality chiefly rests on these volumes which placed him in the front rank of lyric poets.

His worldly prospects were now, in the last decade of the eighteenth century, perhaps better than they had ever been. However, he was simultaneously entering the last and darkest period of his career. He had become soured and had alienated many of his best friends by too freely expressing sympathy with the French Revolution and the then unpopular advocates of reform at home. His health began to give way and he fell into fits of despondency. The habits of intemperance, to which he had always been more or less inclined, grew upon him and contributed to his increasingly bad health. He sadly passed away at the young age of 37 on July 21, 1796.

Within a short time of his death, money started pouring in from all over Scotland to support his widow and children and his memory today is celebrated by Burns Clubs across the world. His birthday is an unofficial national day for Scots and those with Scottish ancestry, called Burns Night, where he is celebrated with Burns Suppers that include haggis and potatoes.

Feeling inspired to write some of your own poetry or lyrics? Why not take a look at our stationery collection, for it is certainly much easier today to get oneself a good writing instrument and fresh new notebook to break in!

If you don't want to miss a beat when it comes to Jane Austen, make sure you are signed up to the Jane Austen newsletter for exclusive updates and discounts from our Online Gift Shop.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.