The Barker Family: Panorama Painters

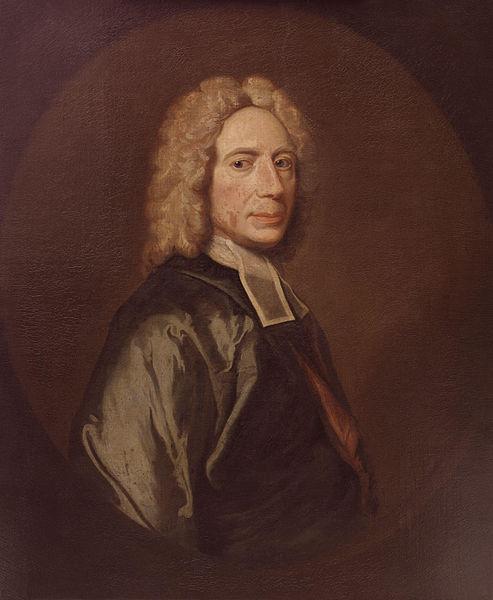

The English itinerant portrait painter Robert Barker (1739–8 April 1806) coined the word "panorama", from Greek pan ("all") horama ("view") in 1792 to describe his paintings of Edinburgh, Scotland shown on a cylindrical surface, which he soon was exhibiting in London, as "The Panorama". In 1793 Barker moved his panoramas to the first purpose-built panorama building in the world, in Leicester Square, and made a fortune.

Viewers flocked to pay 3 shillings to stand on a central platform under a skylight, which offered an even lighting, and get an experience that was "panoramic" (an adjective that didn't appear in print until 1813). The extended meaning of a "comprehensive survey" of a subject followed sooner, in 1801. Visitors to Barker's semi-circular Panorama of London, painted as if viewed from the roof of Albion Mills on the South Bank, could purchase a series of six prints that modestly recalled the experience; end-to-end the prints stretched 3.25 meters.

The English itinerant portrait painter Robert Barker (1739–8 April 1806) coined the word "panorama", from Greek pan ("all") horama ("view") in 1792 to describe his paintings of Edinburgh, Scotland shown on a cylindrical surface, which he soon was exhibiting in London, as "The Panorama". In 1793 Barker moved his panoramas to the first purpose-built panorama building in the world, in Leicester Square, and made a fortune.

Viewers flocked to pay 3 shillings to stand on a central platform under a skylight, which offered an even lighting, and get an experience that was "panoramic" (an adjective that didn't appear in print until 1813). The extended meaning of a "comprehensive survey" of a subject followed sooner, in 1801. Visitors to Barker's semi-circular Panorama of London, painted as if viewed from the roof of Albion Mills on the South Bank, could purchase a series of six prints that modestly recalled the experience; end-to-end the prints stretched 3.25 meters.

When Barker first patented his technique in 1787, he had given it a French title: La Nature à Coup d’ Oeil ("Nature at a glance"). A sensibility to the "picturesque" was developing among the educated class, and as they toured picturesque districts, like the Lake District, they might have in the carriage with them a large lens set in a picture frame, a "landscape glass" that would contract a wide view into a "picture" when held at arm's length.

Despite the success of Barker's first panorama in Leicester Square, it was neither his first attempt at the craft nor his first exhibition. In 1788 Barker showcased his first panorama. It was only a semi-circular view of Edinburgh, Scotland, and Barker's inability to bring the image to a full 360 degrees disappointed him. To realize his true vision, Barker and his son, Henry Aston Barker (1774 - 19 July 1856), took on the task of painting a scene of the Albion Mills. The first version of what was to be Barker's first successful panorama was displayed in the Barker home and measured only 137 square metres.

When Barker first patented his technique in 1787, he had given it a French title: La Nature à Coup d’ Oeil ("Nature at a glance"). A sensibility to the "picturesque" was developing among the educated class, and as they toured picturesque districts, like the Lake District, they might have in the carriage with them a large lens set in a picture frame, a "landscape glass" that would contract a wide view into a "picture" when held at arm's length.

Despite the success of Barker's first panorama in Leicester Square, it was neither his first attempt at the craft nor his first exhibition. In 1788 Barker showcased his first panorama. It was only a semi-circular view of Edinburgh, Scotland, and Barker's inability to bring the image to a full 360 degrees disappointed him. To realize his true vision, Barker and his son, Henry Aston Barker (1774 - 19 July 1856), took on the task of painting a scene of the Albion Mills. The first version of what was to be Barker's first successful panorama was displayed in the Barker home and measured only 137 square metres.

Barker's accomplishment involved sophisticated manipulations of perspective not encountered in the panorama's predecessors, the wide-angle "prospect" of a city familiar since the 16th century, or Wenceslas Hollar's "long view" of London, etched on several contiguous sheets.

Barker's accomplishment involved sophisticated manipulations of perspective not encountered in the panorama's predecessors, the wide-angle "prospect" of a city familiar since the 16th century, or Wenceslas Hollar's "long view" of London, etched on several contiguous sheets.

Barker made many efforts to increase the realism of his scenes. To fully immerse the audience in the scene, all borders of the canvas were concealed.Props were also strategically positioned on the platform where the audience stood and two windows were laid into the roof to allow natural light to flood the canvases.

Barker made many efforts to increase the realism of his scenes. To fully immerse the audience in the scene, all borders of the canvas were concealed.Props were also strategically positioned on the platform where the audience stood and two windows were laid into the roof to allow natural light to flood the canvases.

Two scenes could be exhibited in the rotunda simultaneously, however the rotunda at Leicester Square was the only one to do so. Houses with single scenes proved more popular to audiences as the fame of the panorama spread. Because the Leicester Square rotunda housed two panoramas, Barker needed a mechanism to clear the minds of the audience as they moved from one panorama to the other. To accomplish this, patrons walked down a dark corridor where their minds were supposed to be refreshed for viewing the new scene. Due to the immense size of the panorama, patrons were given orientation plans to help them navigate the scene. These glorified maps pinpointed key buildings, sites, or events exhibited on the canvas.

To create a panorama, artists travelled to the sites and sketched the scenes multiple times. Typically a team of artists worked on one project with each team specializing in a certain aspect of the painting such as landscapes, people or skies. After completing their sketches, the artists typically consulted other paintings, of average size, to add further detail. Martin Meisel described the panorama perfectly in his book Realizations: “In its impact, the Panorama was a comprehensive form, the representation not of the segment of a world, but of a world entire seen from a focal height.” Though the artists painstakingly documented every detail of a scene, by doing so they created a world complete in and of itself.

The first panoramas depicted urban settings, such as cities, while later panoramas depicted nature and famous military battles. The necessity for military scenes increased in part because so many were taking place. French battles commonly found their way to rotundas thanks to the feisty leadership of Napoleon Bonaparte. Henry Aston Barker's travels to France during the Peace of Amiens led him to court, where Bonaparte accepted him. Henry Aston created panoramas of Bonaparte's battles including The Battle of Waterloo, which saw so much success that he retired after finishing it. Henry Aston's relationship with Bonaparte continued following Bonaparte's exile to Elba, where Henry Aston visited the former emperor.

Two scenes could be exhibited in the rotunda simultaneously, however the rotunda at Leicester Square was the only one to do so. Houses with single scenes proved more popular to audiences as the fame of the panorama spread. Because the Leicester Square rotunda housed two panoramas, Barker needed a mechanism to clear the minds of the audience as they moved from one panorama to the other. To accomplish this, patrons walked down a dark corridor where their minds were supposed to be refreshed for viewing the new scene. Due to the immense size of the panorama, patrons were given orientation plans to help them navigate the scene. These glorified maps pinpointed key buildings, sites, or events exhibited on the canvas.

To create a panorama, artists travelled to the sites and sketched the scenes multiple times. Typically a team of artists worked on one project with each team specializing in a certain aspect of the painting such as landscapes, people or skies. After completing their sketches, the artists typically consulted other paintings, of average size, to add further detail. Martin Meisel described the panorama perfectly in his book Realizations: “In its impact, the Panorama was a comprehensive form, the representation not of the segment of a world, but of a world entire seen from a focal height.” Though the artists painstakingly documented every detail of a scene, by doing so they created a world complete in and of itself.

The first panoramas depicted urban settings, such as cities, while later panoramas depicted nature and famous military battles. The necessity for military scenes increased in part because so many were taking place. French battles commonly found their way to rotundas thanks to the feisty leadership of Napoleon Bonaparte. Henry Aston Barker's travels to France during the Peace of Amiens led him to court, where Bonaparte accepted him. Henry Aston created panoramas of Bonaparte's battles including The Battle of Waterloo, which saw so much success that he retired after finishing it. Henry Aston's relationship with Bonaparte continued following Bonaparte's exile to Elba, where Henry Aston visited the former emperor.

Outside of England and France, the popularity of panoramas depended on the type of scene displayed. Typically, people wanted to see images from their own countries or from England. This principle rang true in Switzerland, where views of the Alps dominated. Likewise in America, New York City panoramas found popularity, as well as imports from Barker's rotunda. As painter John Vanderlyn soon found out, French politics did not interest Americans. In particular, his depiction of Louis XVIII's return to the throne did not live two months in the rotunda before a new panorama took its place.

Barker's Panorama was hugely successful and spawned a series of "immersive" panoramas: the Museum of London's curators found mention of 126 panoramas that were exhibited between 1793 and 1863. In Europe, panoramas were created of historical events and battles, notably by the Russian painter Franz Roubaud. Most major European cities featured more than one purpose-built structure hosting panoramas. These large fixed-circle panoramas declined in popularity in the latter third of the nineteenth century, though in the United States they experienced a partial revival; in this period, they were more commonly referred to as cycloramas.

In Britain and particularly in the United States, the panoramic ideal was intensified by unrolling a canvas-backed scroll past the viewer in a Moving Panorama (noted in the 1840s), an alteration of an idea that was familiar in the hand-held landscape scrolls of Song China. Such panoramas were eventually eclipsed by moving pictures. (See motion picture.) The similar diorama, essentially an elaborate scene in an artificially-lit room-sized box, shown in Paris and taken to London in 1823, is credited to the inventive Louis Daguerre (inventor of the Daguerreotype), who had trained with a painter of panoramas. Barker died April 8, 1806, and was buried at Lambeth, Surrey.

Barker's oldest son, Thomas Edward Barker, although not an artist, was also involved in running the family business, but later set up a rival panorama exhibition with the painter Ramsay Richard Reinagle at 168/9 The Strand, London.

As the younger son of the now famous artist, Henry Aston Barker , assisted with and then carried on his father's profession of painting and exhibiting panaoramas. Born in Glasgow, he was, by the age of twelve he was set to work making outlines of the city of Edinburgh from the top of the Calton Hill Observatory, and a few years later made the drawings for the view of London from Albion Mills. He later made etchings after these drawings.

In 1788 Barker moved to London with his father, and soon afterwards became a pupil at the Royal Academy. He continued to be his father's chief assistant in the panoramas till the latter's death in 1806, when, as executor, he took over the business, and carried on the exhibitions for 20 years with great success.

Outside of England and France, the popularity of panoramas depended on the type of scene displayed. Typically, people wanted to see images from their own countries or from England. This principle rang true in Switzerland, where views of the Alps dominated. Likewise in America, New York City panoramas found popularity, as well as imports from Barker's rotunda. As painter John Vanderlyn soon found out, French politics did not interest Americans. In particular, his depiction of Louis XVIII's return to the throne did not live two months in the rotunda before a new panorama took its place.

Barker's Panorama was hugely successful and spawned a series of "immersive" panoramas: the Museum of London's curators found mention of 126 panoramas that were exhibited between 1793 and 1863. In Europe, panoramas were created of historical events and battles, notably by the Russian painter Franz Roubaud. Most major European cities featured more than one purpose-built structure hosting panoramas. These large fixed-circle panoramas declined in popularity in the latter third of the nineteenth century, though in the United States they experienced a partial revival; in this period, they were more commonly referred to as cycloramas.

In Britain and particularly in the United States, the panoramic ideal was intensified by unrolling a canvas-backed scroll past the viewer in a Moving Panorama (noted in the 1840s), an alteration of an idea that was familiar in the hand-held landscape scrolls of Song China. Such panoramas were eventually eclipsed by moving pictures. (See motion picture.) The similar diorama, essentially an elaborate scene in an artificially-lit room-sized box, shown in Paris and taken to London in 1823, is credited to the inventive Louis Daguerre (inventor of the Daguerreotype), who had trained with a painter of panoramas. Barker died April 8, 1806, and was buried at Lambeth, Surrey.

Barker's oldest son, Thomas Edward Barker, although not an artist, was also involved in running the family business, but later set up a rival panorama exhibition with the painter Ramsay Richard Reinagle at 168/9 The Strand, London.

As the younger son of the now famous artist, Henry Aston Barker , assisted with and then carried on his father's profession of painting and exhibiting panaoramas. Born in Glasgow, he was, by the age of twelve he was set to work making outlines of the city of Edinburgh from the top of the Calton Hill Observatory, and a few years later made the drawings for the view of London from Albion Mills. He later made etchings after these drawings.

In 1788 Barker moved to London with his father, and soon afterwards became a pupil at the Royal Academy. He continued to be his father's chief assistant in the panoramas till the latter's death in 1806, when, as executor, he took over the business, and carried on the exhibitions for 20 years with great success.

He frequently traveled in the course of his work, and in August 1799 left England for Turkey, to make drawings for a panorama of Constantinople. At Palermo, he called on Sir William Hamilton, the English ambassador to the court of Naples, who introduced him to Lord Nelson, who, he wrote, "took me by the hand and said he was indebted to me for keeping up the fame of his victory in the Battle of the Nile for a year longer than it would have lasted in the public estimation" (Barker's memoranda). The panorama of Constantinople was exhibited in 1802, and the drawings were engraved and published in four plates.

In 1801, Barker went to Copenhagen to make drawings for a picture of the battle, and while there he was again received by Nelson. In May 1802, during the Peace of Amiens, he went to Paris and made drawings for a panorama of the city. After this many other panoramas were exhibited, the later ones being chiefly from drawings by John Burford, who shared with Barker the property in a panorama in the Strand, purchased in 1816 from his brother, Thomas Edward. Barker, however, still traveled from time to time, and visited, among other places, Malta, where he made drawings of the port, exhibited in 1810 and 1812; Venice, of which a panorama was exhibited in 1819; and Elba, where he made the acquaintance of Napoleon.

After the Battle of Waterloo, Barker visited the field, and went to Paris, where he obtained from the officers at headquarters all necessary information on the subject of the battle. A series of eight etchings by John Burnett from Barker's original sketches of the of the battlefield was published, as were also his drawings of Gibraltar. His last grand panorama, exhibited in 1822, showed the coronation procession of George IV. Of all the panoramas exhibited, that of the battle of Waterloo was the most successful and lucrative. By the exhibition of this picture Barker realised no less than £10,000.

He frequently traveled in the course of his work, and in August 1799 left England for Turkey, to make drawings for a panorama of Constantinople. At Palermo, he called on Sir William Hamilton, the English ambassador to the court of Naples, who introduced him to Lord Nelson, who, he wrote, "took me by the hand and said he was indebted to me for keeping up the fame of his victory in the Battle of the Nile for a year longer than it would have lasted in the public estimation" (Barker's memoranda). The panorama of Constantinople was exhibited in 1802, and the drawings were engraved and published in four plates.

In 1801, Barker went to Copenhagen to make drawings for a picture of the battle, and while there he was again received by Nelson. In May 1802, during the Peace of Amiens, he went to Paris and made drawings for a panorama of the city. After this many other panoramas were exhibited, the later ones being chiefly from drawings by John Burford, who shared with Barker the property in a panorama in the Strand, purchased in 1816 from his brother, Thomas Edward. Barker, however, still traveled from time to time, and visited, among other places, Malta, where he made drawings of the port, exhibited in 1810 and 1812; Venice, of which a panorama was exhibited in 1819; and Elba, where he made the acquaintance of Napoleon.

After the Battle of Waterloo, Barker visited the field, and went to Paris, where he obtained from the officers at headquarters all necessary information on the subject of the battle. A series of eight etchings by John Burnett from Barker's original sketches of the of the battlefield was published, as were also his drawings of Gibraltar. His last grand panorama, exhibited in 1822, showed the coronation procession of George IV. Of all the panoramas exhibited, that of the battle of Waterloo was the most successful and lucrative. By the exhibition of this picture Barker realised no less than £10,000.

Famous battles, like this painting of the 1812 battle of Borodino by Raevsky, were a popular theme for panoramic display. There is currently an immersive panoramic exhibit

In about 1802 Barker married the eldest of the six daughters of Rear Admiral William Bligh, who commanded the Bounty at the time of the celebrated mutiny. By her Barker left two sons and two daughters. In 1826 he transferred the management of both the panoramas to John and Robert Burford, and went to live first at Cheam, in Surrey, and then near Bristol.

Famous battles, like this painting of the 1812 battle of Borodino by Raevsky, were a popular theme for panoramic display. There is currently an immersive panoramic exhibit

In about 1802 Barker married the eldest of the six daughters of Rear Admiral William Bligh, who commanded the Bounty at the time of the celebrated mutiny. By her Barker left two sons and two daughters. In 1826 he transferred the management of both the panoramas to John and Robert Burford, and went to live first at Cheam, in Surrey, and then near Bristol.

Barker died on 19 July 1856 at Belton near Bristol. A list of most of the panoramas painted and exhibited by Henry and Robert Barker was published in The Art Journal (1857, p. 47).

Barker died on 19 July 1856 at Belton near Bristol. A list of most of the panoramas painted and exhibited by Henry and Robert Barker was published in The Art Journal (1857, p. 47).

Historical information from Wikipedia.com.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.