All Hallow's Eve

Halloween, Hallowe’en, All Hallow’s Eve…they all sound mysterious and spooky; but where did this celebration of the underworld come from and when did it begin? Did Jane Austen ever go trick-or-treating? The celebration now known as Halloween has its roots in the Celtic festival of Samhain, one of the four Druid “Bonfire” festivals. Celebrated on November 1, midway between the Autumn and Winter Solstices, some scholars believe that it marked the end of the old year and start of the new.

Halloween, Hallowe’en, All Hallow’s Eve…they all sound mysterious and spooky; but where did this celebration of the underworld come from and when did it begin? Did Jane Austen ever go trick-or-treating? The celebration now known as Halloween has its roots in the Celtic festival of Samhain, one of the four Druid “Bonfire” festivals. Celebrated on November 1, midway between the Autumn and Winter Solstices, some scholars believe that it marked the end of the old year and start of the new.

Samhain (pronounced sów-en) was not a god to be worshipped, but rather a term meaning “The End of Summer”. It was at this time that the harvest was brought in, preparations for winter completed, debts were settled and the dead buried before the coming winter. In the highly superstitious Celtic culture, it was also believed that at this time when “a new year was being stitched to the old” the veil between the present world and the next was especially thin, allowing the spirits of the departed, both good and evil to roam.

Because of this belief, October 31 became a highly superstitious night. Some used the opportunity to entreat the dead for guidance in the coming year. Others carried on traditions involving the revelation of one’s sweetheart or good fortune for the coming year. Towards the close of the evening priests and townsfolk, dressed as spirits would parade through the village in order to lead the wandering ghosts back to their resting places. Far from being a burning Hell, the Celtic “underworld” was a place of light and feasting, much more akin to the Christian ideal of Heaven.

As it was also the close of the year, the bonfire, kindled by the priests served an extra purpose. Each villager would let their hearth fire die out that night to be lit afresh by embers from the bonfire, symbolising a new year and hope for prosperity. During the night of spooks and ghosts, homes would be lit by rustic lanterns carved from turnips (known early on as neeps) beets and rutabagas.

Pumpkins would be used later, as they were brought to Europe from the New World in the 17th century. These flickering lights were set out in hopes of welcoming home friendly souls and chasing away the evil spirits who wandered that night. Another important part of the celebration’s revelries included lawlessness and mischief. It was during this time that rules were lifted and pranksters were given a free hand.

Cows would be found it far off fields, gates unhinged, women dressed in men’s clothing and servants ruled their masters.  When the Romans conquered Britain in AD 43 they drove the Celts to Scotland and Ireland, building Hadrian’s Wall across Britannia in order to protect their settlements from raiders, officially dividing the two countries. Though they brought with them their own polytheistic religion, they were not above incorporating the holidays already in place in the land, adding a celebration to their goddess of fruit trees, Pomona, to the revelries, forever linking apples and feasting to Halloween.

When the Romans conquered Britain in AD 43 they drove the Celts to Scotland and Ireland, building Hadrian’s Wall across Britannia in order to protect their settlements from raiders, officially dividing the two countries. Though they brought with them their own polytheistic religion, they were not above incorporating the holidays already in place in the land, adding a celebration to their goddess of fruit trees, Pomona, to the revelries, forever linking apples and feasting to Halloween.

The result of the Roman invasion and subsequent adoption of the Julian Calendar, which moved New Year’s Day to January 1st, was that for some, the entire period between October 31st (the Old New Year) and January 1st became a time when Ghosts were free to wander the earth and meddle in the affairs of mortals.

It was with this in mind that, in 1843, Charles Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol as a ghost story. A vivid picture of this kind of nocturnal wandering can be found in Ebenezer Scrooge’s first meeting Marley’s Ghost.

“The air was filled with phantoms, wandering hither and thither in restless haste, and moaning as they went. Every one of them wore chains like Marley's Ghost; some few (they might be guilty governments) were linked together; none were free. Many had been personally known to Scrooge in their lives. He had been quite familiar with one old ghost, in a white waistcoat, with a monstrous iron safe attached to its ankle, who cried piteously at being unable to assist a wretched woman with an infant, whom it saw below, upon a door-step. The misery with them all was, clearly, that they sought to interfere, for good, in human matters, and had lost the power for ever.”

Such was the power of tradition begun by the Druids. With the spread of Christianity in the 7th-10th centuries came the desire by the church to wipe out pagan rituals and holidays and replace them with festivals of Christian significance. Accordingly, Pope Gregory III (731–741) moved All Saints Day (originally celebrated on the first Sunday after Pentecost, signaling the official end of Easter) from May to November 1, followed by All Souls Day on November 2. All Saints Day, which involves a vigil kept the night before (October 31) was set aside to commemorate all saints two numerous to be given their own feast day. With the far reaching influence of the Catholic church, the day was soon celebrated across Europe and later the Americas.

All Souls day became a day for celebrating the memory of the dead, whose souls were still in purgatory. Beggars would traipse from door to door pleading “soul cakes” from each home in return for prayers made for their relatives. This connection with the departed tied the holiday once again to the earlier festival of Samhain. The new name, Halloween came from the Christian Festival. As a night of vigil, the 31st was a “Hallowed Evening”, shortened to Hallowe’en and then Halloween. It was also known as Hallowmas, a begging holiday, as mentioned in Shakespeare’s Two Gentlemen of Verona when Speed accuses his master of "puling (whimpering and whining) like a beggar at Hallowmas."

In 1605, a group of Catholic rebels planned to blow up Parliament in the now famous Gun Powder Plot. The plan was discovered and on November 5, key insurgent Guy Fawkes was arrested. Though he was later executed for treason, the day of his arrest became a holiday and the bonfires which once burned on October 31st were now lit on November 5th.

In 1605, a group of Catholic rebels planned to blow up Parliament in the now famous Gun Powder Plot. The plan was discovered and on November 5, key insurgent Guy Fawkes was arrested. Though he was later executed for treason, the day of his arrest became a holiday and the bonfires which once burned on October 31st were now lit on November 5th.

Guy Fawkes Day became a time of revelry and mischief. Though “souling” had since died out, children would often beg pennies off of passing adults in order to buy fireworks for the night’s illuminations, keeping alive the tradition of ritual begging. Later, under the puritanical rule of Oliver Cromwell, Halloween, as well as most other holidays and feast days were abolished. For many years there had been a push to eradicate witches, with whom the festival was especially popular, and even cats who were seen as their familiars (a spirit guide who takes the form of an animal) This destruction of cats may have actually hastened the spread of the Bubonic Plague (Black Death) in which is spread by rats and fleas. The London outbreak in 1665-1666 killed between 75,000 and 100,000 people—one fifth of the city’s population.

The Celts who populated Scotland and Ireland, however, were loathe to relinquish their old ways in favour of Christian feast days or lack there of. Instead, they incorporated these new rites into the old celebration. It is clear from Scottish poet Robert Burns’ 1786 work, Halloween, that by Georgian times, the holiday was still alive and well, with much of its superstitious symbolism intact. The poem describes the tricks (such as eating an apple in front of a mirror in hopes of seeing your beloved) and treats (Flummery and Barmbrack) of the season to which most Scots or Irishmen would have been familiar.  T

T

he extended Regency was an era fascinated by the mysterious and horrible. Frightening gothic romances, such as The Mysteries of Udolpho, were being written and were read by all. Some of the more familiar icons of modern Halloween such as Frankenstein (1816) and The Headless Horseman (brought to life in The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, 1820) were created during this era.

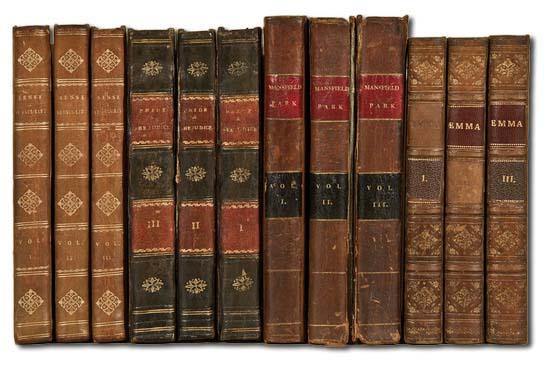

Jane Austen, an avid reader with a taste for novels was no doubt familiar many of these gothic masterpieces as well as with the work of Robert Burns. She would have been aware of these celebrations and divination rites; however, as the daughter of an Anglican clergyman, it is doubtful that she would have partaken in such goings on. Surely, growing up in a houseful of boys, she would have celebrated with a bonfire on Guy Fawkes night, but we nowhere find that she dabbled in any of the occultic practices of the more ancient holidays still celebrated by the local villages.

She mentions neither of these holidays or her feelings towards them. The trappings of Halloween which we now so regularly employ would have been foreign to her, even if their roots lay deep in the English history, of which she was so fond. Halloween was brought to the United States by Irish settlers in the 1840’s where it was eventually embraced by all nationalities. In 1915, the Boy Scouts of America scheduled the first “trick-or-treating” as a way of discouraging damaging mischief, but it was not until 1938 that the term actually appeared in print. As each decade since has passed, costumes, parties and decorations have become more elaborate finally evolving into a multimillion  dollar industry replete with specially wrapped candies, ornate costumes and a fascination with all that is frightening and evil. This lack of evidence supporting a universal celebration of Halloween in Georgian and Regency England has not stopped numerous authors from sliding it into their works. There are many “Regency” inspired novels now in print which employ elements of the various superstitions of the holiday as well known fact, some employing the paranormal, and others playing off the themes of Harvest and plenty.

dollar industry replete with specially wrapped candies, ornate costumes and a fascination with all that is frightening and evil. This lack of evidence supporting a universal celebration of Halloween in Georgian and Regency England has not stopped numerous authors from sliding it into their works. There are many “Regency” inspired novels now in print which employ elements of the various superstitions of the holiday as well known fact, some employing the paranormal, and others playing off the themes of Harvest and plenty.

If you don't want to miss a beat when it comes to Jane Austen, make sure you are signed up to the Jane Austen newsletter for exclusive updates and discounts from our Online Gift Shop.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.