Jane Austen’s Early Fangirls

It used to be ironclad tradition to describe Jane Austen Q-U-I-E-T-L-Y. One mass-market paperback edition of her novels featured a foreword calling her life “uneventful, placid, and circumscribed” and ending un-triumphantly, “the author died, as quietly and serenely as she had lived.”

Dull, dreary, and uninspiring as this life summary sounds, the scholarly consensus and popular meme had a positive kernel of truth, as they often have. Austen did live a life of quiet dignity, because she believed in doing so for ethical reasons, and she turned down opportunities to become a literary lion.

But over-emphasizing the quietness undersells both Jane’s eventful life and the early success of her novels. In historical fact, her books enjoyed quite a lively if manageable vogue. A developing fandom began showing up in print early. From 1811, when Sense and Sensibility was published, through 1817, when she died, and throughout the Regency and Romantic periods, Jane Austen’s novels were read, recommended, and ‘tagged’ in books published in Britain and in the United States. Other authors borrowed from, emulated, or tried to piggyback on her works, and several indulged in enthusiastic references to Austen herself. This short article concerns the direct references; to discuss the indirect tributes would exceed the scope here.

The kicker is that the references came from other novelists. Literary reviewers in periodicals praised her work, of course—Sir Walter Scott, also a novelist, being one famous example--but so did fictional characters in novels. Writers may be proverbially a waspish bunch, not to be trusted any farther than they can throw each other behind their respective backs, but they seem mostly to have set aside their sharp edges with Austen, leaving the weapons outside a charmed circle like later Mob bosses enjoying a fashionable watering hole. During research for a book on Pride and Prejudice, I have found several references in contemporaneous novels showing that fellow authors—especially sister authors--read Austen with admiration and were willing to say so.

The first out-and-out plug for Austen in a novel appeared in July 1817, the month of Jane Austen’s death. he work was a witty parody of gothic novels titled The Hero, or the Adventures of a Night, translated from French into English by Sophia Lewis Shedden. Shedden, as it happened, was the younger sister of author Matthew Lewis, who had created the gothic best-seller The Monk (praised by John Thorpe in Northanger Abbey). Like horror movies today, gothic novels ranged in quality from lurid schlock to smart self-parodies, and Austen and her family would have enjoyed Shedden’s smart translation, which boosted Austen’s novels specifically. In the main story line, the central character is addicted to gothic romances, and his daughter’s fiancé undertakes to rehabilitate him with a friend’s help. Finally, a mysterious ‘fiend’ compels the hero-for-a-night to promise that he will never read another gothic novel. The spurious fiend, an acquaintance in disguise, presents him with a contract to sign, binding him, “as long as you live,” never to read “any English novels,” except by a famous few like Fielding, Smollett, and Sir Walter Scott—"and Pride and Prejudice, with others by the same author.”

The firm of Matthew Carey in Philadelphia, which had published Emma the year before and would publish Austen’s complete novels in 1832 and 1833, brought out a second edition of The Hero in 1817. Carey recognized a plug when he saw one.

Ann Kelty's The Favourite of Nature

Sophia Shedden’s reference was only one of the more direct indications that Austen’s fan networks began growing early. For a quick overview, in 1821, Mary Ann Kelty’s The Favourite of Nature contained a shopping list reminding the heroine to buy Austen’s novels. Then came Thomas Henry Lister’s Granby in 1826; American novelist Mary Jane Mackenzie’s Private Life, or Varieties of Character and Opinion in 1829; Catherine Grace Gore’s Manners of the Day in 1830; and Letitia Elizabeth Landon’s Romance and Reality in 1831, all mentioning either Austen by name or her novels by title, or both.

Mackenzie, Private Life

Gore's Manners of the Day

Landon's Romance and Reality

The different authors had different styles--showing the breadth of Austen’s appeal. Some authors who explicitly plugged Jane Austen mentioned her more than once, like Mary Jane Mackenzie, who in Private Life created a book club, extended literary conversations, and a main character, Constance, appreciative and informed about literature, discussing and recommending the writing of “Miss Austen.” In other novels, Austen is mentioned briefly, in a quick, passing reference evidently needing no explanation, as in Shedden’s translated gothic spoof.

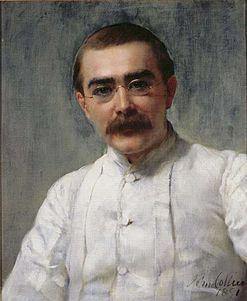

More than once, a novelist who mentioned Austen made her a literary touchstone. Beware of any fictional character from this period who does not like Austen; such lack of taste is self-condemning, revealing either character flaw or lack of intellect, as with Mackenzie’s character who cannot tell Jane Austen from Mary Russell Mitford. (Mitford herself praised Austen as “the most correct of female writers.") In Lister’s Granby, a fashionable chatterer unwittingly reveals her ignorance when she rejects Austen and mistakes Northanger Abbey for a typical pulp-mill gothic romance. [ILL 7 Lister] Landon’s characters who criticize Austen are also unwittingly self-condemning.

Mary Russell Mitford

Lister, Granby

As indicated, there are other references and tributes from the early years, direct and indirect. Summing up, the spontaneous admiration manifested both in nonfiction and in fiction, and the writers’ tributes began before Carey and Lea brought out their new (cheaper by a third) edition of Austen’s novels in 1832 in Philadelphia and Richard Bentley brought out his edition in 1833 in London. Among people who read novels--meaning most people who could read—Austen’s popularity began early. And while some of the tributes are brief or subtle, again these are references in other novels, inserted as part of the story, where Austen is name-dropped in characters’ dialogue or by the narrator, sometimes humorously but always with goodwill. In context, they are rather impressive signs of fandom when one remembers that there was no publicity tour, no celebrity subscription list, and only a modest launch party.

Austen’s novels stood or fell entirely on their own merits.

About the AuthorMargie Burns, Ph.D., author of “Jane Austen’s Early Fangirls,” is a writer with academic training and experience. She lectures as an adjunct in English at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Her latest book is Publishing Northanger Abbey: Jane Austen and the Writing Profession

Contact at margie.burns@gmail.com.

If you would like to contribute to the Jane Austen blog, check out this page for more information.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.