Jane by Any Other Name - The Dutch Translations of Jane Austen

The Dutch Translations of Jane Austen

Until 1870, the year when James Edward Austen-Leigh published his Memoir, Jane Austen, was, in the words of B.C. Southam "never thought of as a popular novelist nor did she get much attention from the Victorian critics and literary historians". It is therefore not surprising that it took a considerable time before her works became available in translation abroad, unlike those of Scott and of the major Victorian novelists, whose works rapidly found numerous translators on the Continent. Then, too, Southam asserts that she was "not a European novelist", which he attributes to the fact that "the quality inherent in her tone and style was untranslatable". It was only in the past century that her works found renditions into a large variety of languages, including the Dutch. This essay seeks to offer some inside information on these Dutch translations as well as to assess their merits, and, if possible, to map the critical response they received.

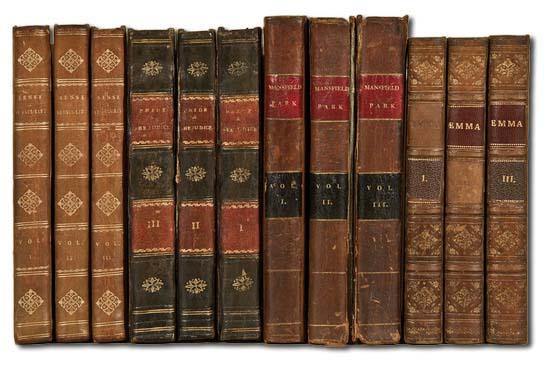

The first Dutch translation of a work by Jane Austen was published in 1922. Entitled Gevoel en verstand (Sense and Sensibility (1811)), it was brought out by the Amsterdam-based "Maatschappij voor goede en goedkope Lectuur" ("Society for Good and Cheap Literature") in its series "Wereldbibliotheek" ("World-Library"), which had been established by Dr. L. Simons (1862-1952) in 1905 with the express purpose of making available cheap editions of the most outstanding works in world-literature. Since its foundation "Wereldbibliotheek" was to issue hundreds of native as well as translated foreign works in millions of copies. Prior to Gevoel en verstand this series had published several noted translations of English poets, including Hélène Swarth’s translation of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Portuguese Sonnets (1915) as well as Alex Gutteling’s Dutch rendition of Paradise Lost (1912).

The price for each copy in this popular series was indeed competitively low, namely around 1 Dutch florin. The translation of Sense and Sensibility was made by Hillegonda van Uildriks, alias Gonne Loman-van Uildriks (1863-1921), an aspiring poetess, but chiefly known as a professional translator, who had already furnished several Dutch translations of English literature, including works by H.G. Wells, R.L. Stevenson, J. Ruskin, E.A. Poe, H. Walpole etc. Gevoel en verstand was prefaced by an Introduction, which is worth bringing into focus, for it is one of the earliest Dutch commentaries on Jane Austen’s genius. This two-page account by an anonymous editor, but almost certainly from the pen of Dr. Simons, set out to sketch a brief life of Jane Austen, stressing the difficulties she had encountered in getting her novels published. He then characterized the "great quality" of her work as follows:

it is the subtle ironic observation of contemporary middle-class life and her power to make this absorbing without any romantic artifice. Her characters and their environment live for us in complete purity, and in her time, in which everything was romanticized, this quality came as such a great surprise that even the Romantic master Walter Scott praised it robustly. There is no English fiction that moves us so much as Jane Austen’s because of its affinity with our own Dutch literature.Interestingly, this critic compared Jane Austen with Betje Wolff (1738-1804) and Aagje Deken (1741-1804), both Dutch female writers, who in collaboration published some famous novels still viewed as classics in Dutch literature. But the English authoress’s work, he went on to say, "is purer in its absence of all sentimentality". We have to wait until 1946 for the following Dutch translation of one of Jane Austen’s novels, namely Trots en vooroordeel (Pride and Prejudice (1813)), published by the Flemish publisher Jos Philippen of the Diest-based firm "Pro Arte". The translation had been assigned to Dr. Fr. Verachtert (1900-1988), a Flemish writer of regional short stories, who also provided some English and German translations. He offered an Introduction to Trots en vooroordeel, which broached some critical remarks on Austen’s art worthy of some attention. Verachtert styled Austen’s "strength" as lying

in the delineation of the characters, especially of female nature. She achieves a strong delineation by recording trivial incidents and traits from the common daily life of middle-class people and the lower aristocracy. Her characters are always drawn with a very firm and precise hand and they are masterfully sustained in the course of the narrative. Never are they coloured by the authoress’s own personality. Jane Austen evidences sufficient detachment towards her work not to have her characters act according to her own nature or her own theories. Life to her is in general attractive and the imperfections it displays, are described with a mild humour. Outbursts of deep feelings rarely occur in her works. In short, she is detached and reserved, two qualities that point to a strong self-control, which usually benefits creative work.

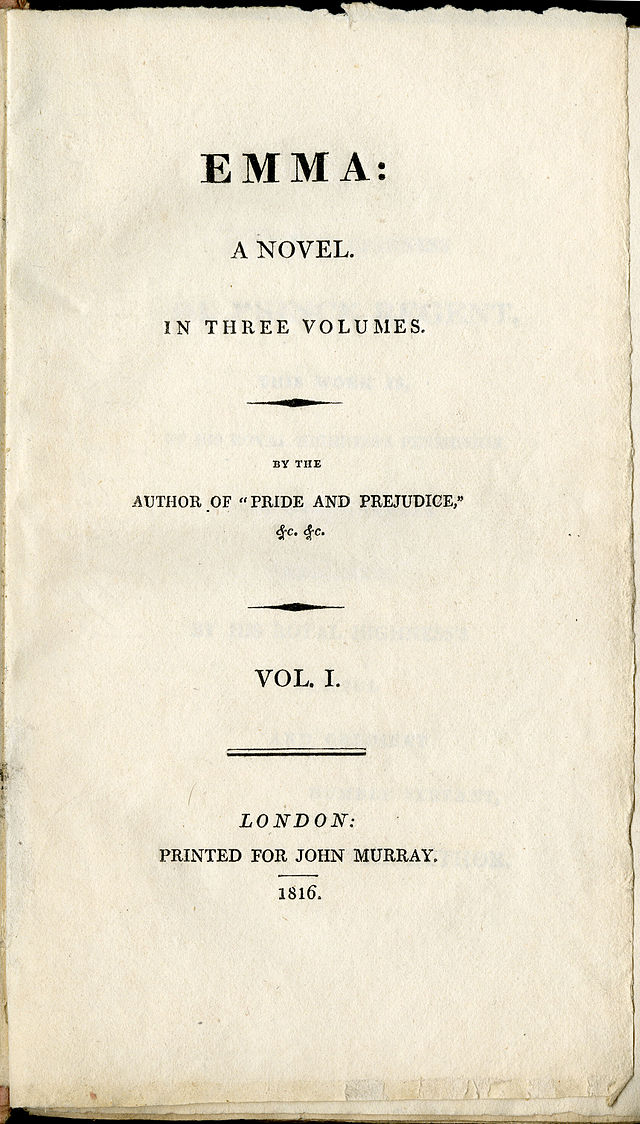

Verachtert further quotes from Scott’s well-known review of Emma (1815) in the Quarterly Review of 1816, also referring to Coleridge’s and Southey’s admiration of her work. Trots en vooroordeel featured one illustration, an engraving made by the internationally renowned artist Nelly Degouy (1910-1979), who in these years engraved numerous illustrations to bibliophile editions.

Three years later, in 1949, the publishing company Het Kompas from Antwerp, brought out a translation of Emma (Emma (1815)) in its series "De Feniks" ("The Phoenix"), which, set up in the early 1930s, brought out important, chiefly Flemish, belletristic work as well as numerous translations of famous foreign novels, including Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, Thackeray’s Henry Esmond, Kipling’s The Light that Failed, Wilde’s The Portrait of Dorian Gray, Conrad’s The Shadow Line, etc. Het Kompas expired at the end of the 1940s. The rendition of Emma was made by Johan Anton Schroeder (1888-1956), a graduate in classical languages from the University of Amsterdam, who became a versatile author on antiquity as well as a noted translator. Het Spectrum, established at Utrecht in 1935, was one of the first Dutch publishing companies in the Netherlands to launch Dutch paperback editions, which were continued after the war under the name "Prisma Pockets".

This extremely popular series, a copy of which was initially available at 1 Dutch florin only, was to offer a great many classics in translation, including several works by Jane Austen. In 1954 the house published Meisjeshoofd en meisjeshart (Sense and Sensibility (1811)), as a Prisma Pocket, actually a reprint of the 1922 Wereldbibliotheek’s Gevoel en verstand. This rendition sold well, for it reached three editions. In the 1980s in particular Het Spectrum brought out four translations of Jane Austen’s novels in paperback. In 1980 Emma was published in a translation by Carolien Polderman-De Vries, whom I have been unable to identify. To this work an Afterword was affixed, signed by a Jenny Leach-Reitsma, which briefly outlined the rise of the English novel in the eighteenth century, thereby mentioning its most celebrated practitioners. But Jane Austen has, Leach-Reitsma argued, "excelled them all" in her masterpieces. Their exciting construction, insight into human nature, and brilliant style are qualities which do not become obsolete like changing rules of conduct, and Jane Austen’s works remain of current interest and are widely read". As to Emma itself, Leach-Reitsma describes the novel as "a good example of a close structure, in which all the fractions indispensably contribute to the build-up and tension of the whole; each scene, each conversation, explains or develops the plot", adding that Austen’s "acute powers of observation combined with her clear psychological insight and especially her sense for the humorous enable her to penetrate deeply into human nature". Such commentary must have greatly familiarized Jane Austen’s genius to a large Dutch-speaking audience. In the same year, 1980, Prisma came out with Waan en eigenwaan (Pride and Prejudice (1813)) in a translation by W.A. Dorsman-Vos, a prolific professional translator, who furnished Dutch translations of, amongst others, George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss, and novels by Margaret Drabble and V.S. Naipaul. She also offered some remarkable introductory lucubrations on Jane Austen, entitled "Jane Austen and her Times - Jane Austen in the Times".

There is no need here to dwell on her commentary in detail. Suffice it to say that it reveals a close acquaintance with Jane Austen’s career and the reception of her works. But perhaps citing a few striking remarks from her piece may be in place. Dorsman-Vos describes Waan en eigenwaan as a "pure novel", that is, "a structured narrative about recognizable people with recognizable reactions to each other and to the circumstances and incidents.

That after two centuries the reader still identifies with the characters in her novels is abundant proof of her mastery." Mentioning the absence of references in Jane Austen’s works to the contemporary dramatic events such as the French Revolution, the Napoleonic campaigns, the Battle of Waterloo and the Industrial Revolution, Dorsman-Vos speculates: "How her books would have looked, when she would have incorporated this turmoil in her fiction, one can only guess, but they would certainly have lost something of their purity and they would have been more anchored in history and therefore would have more rapidly become obsolete". In 1882 Prisma published Verstand en onverstand (Sense and Sensibility), again rendered into Dutch by Mrs. Dorsman-Vos and again she provided an interesting Afterword, which focused on the most salient qualities of Jane Austen’s art. "Jane Austen was a born authoress", she writes, "who had set herself the task of teaching self-knowledge to her contemporaries by holding a mirror to them, often a laughing-mirror". "Her sober shrewdness", Dorsman-Vos continues, "reveals itself time after time in the clear construction of her novels. Each character, each scene receives its function; each advent, each exit is carefully placed and has its function.

She practises a cool self-discipline with the means she employs to give her characters depth and to make the incidents credible" and "The means employed by Jane Austen are contrast and irony". Finally, in 1983 Prisma published Mansfield Park (Mansfield Park (1814)), once more translated by Mrs. Dorsman-Vos and once more she wrote a perceptive coda, which outlined the novel’s plot as well as the women’s plight in the early nineteenth century.

Not surprisingly, various Dutch publishing companies tried to cash in on Jane Austen’s by now huge success in both the Netherlands and Flanders. In 1980 the Utrecht-based publisher L.J. Veen, since 1887 specializing in printing famous Dutch and Flemish authors as well as classics from world-literature, brought out in its series "Amstelpaperbacks" Trots en vooroordeel (Pride and Prejudice) in a translation by H.E. van Praag, who remains unidentified. There were no introductory remarks, but the book-wrapper eloquently advertised the novel in the following terms: "The characterizations, the description of the mutual relations and the picture of the age that this book offers, makes Trots en vooroordeel one of the best novels in English literature". The following year "Amstelpaperbacks" offered a handsome reissue in hardback of J.A. Schroeder’s 1949 translation of Emma. In the following two decades the number of Dutch translations of Jane Austen’s works increased considerably, especially after the hugely popular television serialization of Pride and Prejudice as well as the triumphant film-productions ofSense and Sensibility, Persuasion, and Emma. In 1994 Boekwerk from Groningen published Verstand en gevoel (Sense and Sensibility) in a translation by Elke Meiborg, who after her graduation in English at the University of Groningen in 1990, took up the job of a freelance translator, offering Dutch renditions of Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters, Elizabeth Gaskell and some short stories by Katherine Mansfield. Meiborg furnished an introductory note to Verstand en gevoel, which succinctly characterized Austen’s art as follows: the authoress puts the emphasis on "the mutual relations of the characters or of their relation to a particular theme. Austen takes up a moralistic attitude in all her work, but keeps aloof from all sentimentality.

In her own refined perceptive way she analyzes her characters, their deeper motives and ways of thought. Subtle and full of irony she gives evidence of her contempt for qualities such as egoism and stupidity." This publication ran to four editions. In 1996 the same house brought out Overtuiging (Persuasion (1818)), again in a translation by Elke Meiborg. The book’s cover featured a fine coloured copy of a picture entitled "Veel Vindet", painted by the famous Norwegian artist Hans Olaf Heyerdahl (1857-1913) in 1881. The Introduction to the translation took over that ofVerstand en gevoel, adding a synopsis of the novel’s plot. Miss Meiborg told me that of her translations about 5,000 to 6,000 copies were printed, which is a huge amount in book-production in the Low Countries. In 2000 not less than three Dutch translations of Emma were in circulation. Pandora Klassiek published Schroeder’s by now old-fashioned rendition of the novel and the famous publishing company Athenaeum Polak and Van Gennep launched a new splendidly printed hardback version of Emma, from the pen of Annelies Roeleveld, who was assisted by Margret Stevens. Miss Roeleveld, an anglicist by training with a special interest in English linguistics and currently connected as a researcher with the University of Amsterdam, has also been so kind as to provide me with particulars on this fine edition. 3,000 copies of it were printed, all of which were sold out so that in 2001 a second edition in paperback was brought out, which again, as Roeleveld told me, has been almost exhausted

. Karen van Velsen described this Dutch version of Emma as "comparable in all aspects with the original. In short, a delight to read!" Interestingly, Roeleveld’s translation of Emma was used in 2000 by the The Hague-based publishing company XL for a publication printed in capitals for the sake of visually handicaped readers. Finally, in 2000 the Dutch Reader’s Digest, in its series "The World’s Most Beloved Books", brought out a hardback edition of Verstand en onverstand, in W.A. Dorsman-Vos’s translation. As far as I know, this was the only Dutch Austen book that featured several engravings, made by Hugh Thomson (1860-1920), the well-known illustrator of English classics. In retrospect, then, despite the Flemish and Dutch publishers’ rather late interest in offering a translated Austen to their audience, from the mid-1940s it could relish her major works in translation with the exception of Northanger Abbey (1818). Dutch renditions of Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, and Emma became widely available from the 1980s onwards. There can be no doubt that the successful television serialization and the film version of several of Jane Austen’s works contributed considerably to the dissemination of her translated fiction in the Low Countries, a view also taken by Miss Meiborg in her private communication to me. This is a pleasant afterthought. Film and television adaptations of Jane Austen’s fiction apparently sharpened the reader’s appetite for going to the printed works.

****

"Jane By Any Other Name - The Dutch Translations of Jane Austen" Essay is written by Professor Oskar Wellens of the Free University of Brussels, Belgium.

2 comments

And there’s this translation of Sense and Sensibility: “Meisjeshoofd en meisjeshart” https://www.comicalfellow.com/post/111976462359/meisjeshoofd-en-meisjeshart-jane-austens-sense

Comi Cal Fellow

Hello,

I have just come across an article you published about Mrs Dorsman-Vos and her translations ofr Jane Austin. Would you by any chance know whether Mrs. Dorsman-Vos is still alive and if so, how she can be contacted? She translated quite a few works by my grandmother, Jean Rhys. Any information would be most welcome, including whether she has any family or heirs.

Thank you

Ellen Moerman

Ellen Moerman

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.