Women's Circles Broken - Part Two

Women's Circles Broken: The Disruption of Sisterhood in Three Nineteenth-Century Works

The author of the following work, Meagan Hanley, wrote this multi-part post as her graduate thesis. Her focus was works of literature by female authors, one of whom was Jane Austen. We thought that the entire essay was wonderful, and so, with her permission, we wanted to share it with you.

(This is part two of the essay. Part one can be found here.)

***

PRIDE AND PREJUDICE: THE MEN ENTER THE SCENE

Pride and Prejudice is the oldest text under discussion and is a good fit for the first chapter in other ways as well. Its author was devoted to her older sister Cassandra; the two of them were inseparable for all of Jane’s life. After Cassandra’s fiancé died during a shipping voyage, she was devastated and remained unmarried for the rest of her life. Jane, as far as we know, was engaged for one night but broke it off the next morning and never married. In her article, “Jane Austen's ‘Schemes of Sisterly Happiness’,” Leila S. May writes: “As countless critics and biographers have noted, Austen’s relation to Cassandra was characterized as a ‘marriage,’ a bond so profound that it provided the kind of emotional force and fulfillment which a conventional marriage could only hope to approximate” (May). The two sisters kept an extensive correspondence during the times when they were visiting various family members and friends. Through these letters, readers get a better glimpse of Jane’s personality and the bond she and her sister shared in the lightheartedness seen in letters such as this one she wrote in 1796: “My dearest Cassandra, The letter which I have this moment received from you has diverted me beyond moderation. I could die of laughter at it, as they used to say at school. You are indeed the finest comic writer of the present age” (Chapman). In other letters, it is clear that Jane was an even wittier and more astute social critic than she allowed herself to be when she wrote her novels. Sadly, Cassandra destroyed many of the letters after Jane’s death, but the remaining letters still fill a voluminous collection published by Oxford University Press. It is through these missives that we see the woman behind the famous author and the real relationship between the two sisters—a relationship that was most likely the basis for Jane and Elizabeth Bennet’s relationship in Pride and Prejudice.

Many Austen biographers attempt to focus on the small details in Austen’s life that could have been the basis for her novels—engagements, heartbreak, languishing for lost love—when most likely it was her relationship with Cassandra that both inspired her and made her writing possible. If Austen had been married, it is fairly certain she would not have written her novels, or at least not had them published. It was not for lack of trying on their parents’ part that both sisters never married, but when Cassandra’s fiancé died and Jane refused her final marriage proposal, even their mother said that “’Jane and Cassandra were wedded to each other’...The combined state of singlehood and sisterhood clearly provided the material situation that made Jane Austen’s literary career possible” (McNaron 59). Because she remained unmarried and lived with her mother and sister, her writing provided a source of income, and Cassandra was a constant sounding board for her ideas. Sisters were integral to both Austen’s reality and to those she created in her fictional worlds of women. Austen’s focus on sisters and circles of women is not a new revelation in literary studies. Anyone who has read at least one of her novels will notice the emphasis on sisterly bonds, displayed most clearly in Pride and Prejudice and Sense and Sensibility, where two sisters in each novel share an especially close connection. When reading criticism about Austen’s sisterhoods, one begins to see a spectrum emerge. On one hand is the belief that Austen revered the sacred bond of sisters and believed that all women were connected, as seen in Michael Cohen’s work:

Austen goes far beyond the novels of education to see what a sister who was not a foil or a rival might actually be like to live with, and by extending sisterhoods she makes visible and believable the almost infinitely drawn out, changeable, but no less real relation that exists among all the women in a given society...Pride and Prejudice insists that all its women are sisters. (Cohen)

Other critics disagree with the idea that sisterhood is a beneficial and enviable thing in the novel; rather, that with the exception of Jane and Elizabeth, “it could almost be said that in this novel—to misquote Sartre—‘l’enfer, c’est les soeurs’” [hell is sisters] (May). Still others write that there exists a deeper connection among women—specifically sisters—that Austen draws to the foreground:

It is most helpful to uncover a balance between the extremes of scholarly thought. Relationships among sisters can be as varied as the women’s personalities, as anyone who has a sister will have proof enough to agree. Neither of these opinions is wrong; however, it is important to realize that the same sister can be “hell” one moment and savior the next.

Although Jane Austen’s novels invariably portray male-oriented relationships since they are about forms of courtship and marriage, she also explores the importance of the heroine’s bond with her sister – a bond that frequently plays a highly conducive role in the development of her identity. Often, the heroines who experience profound sororal connections are indebted to their sisters for moral, social, and emotional education. (Dobosiewics)

Jane and Elizabeth are the closest sisters in the story. The two of them are incredibly open and tell each other nearly everything. Their relationship also displays the ways in which women must communicate differently. At the beginning of the novel, the two sisters wait to tell each other their true feelings: “When Jane and Elizabeth were alone, the former, who had been cautious in her praise of Mr. Bingley before, expressed to her sister just how very much she admired him” (Austen). In public, the women are wary and reserved in their opinions, but later when they are alone together, they can be open and honest in their safe and private environment. Much later in the novel, we see an example of the two of them communicating even without words— “Jane and Elizabeth looked at each other”— and a decision is made (Austen). This type of intimacy and internal communion is not typical, but for these two sisters, it becomes a lifeline.

Where Elizabeth and Jane share everything with each other, the two of them often keep things from their other sisters. Not all sisters are close, but all women are brought together through their common experiences and struggles—especially when it comes to maintaining an identity and community apart from the ones expected by the men in their lives. In Pride and Prejudice, multiple communities of women intersect. One is the central family unit comprised of the five Bennet sisters—Jane, Elizabeth, Mary, Kitty, and Lydia. However, even in this literal “sisterhood,” there are levels of closeness among the sisters. Jane and Elizabeth as the two eldest sisters share the closest bond and seemingly sanest minds of the women in their family. From this closest bond branches off the girls’ mother and three other sisters. Interestingly, the Bennet girls’ mother is not fully included in the family community partially because she constantly strives to control her daughters’ lives by marrying them off to rich men. She hovers on the sidelines believing she is in control, constantly embarrassing her eldest daughters. The youngest daughters Kitty and Lydia are connected through their mutual absurdity, while Mary as the middle child stands aloof with her off- putting and heightened sense of superiority and piety. Interestingly, Mary is the only Bennet sister without a strong personality; she merely drifts silently throughout the novel and pipes up every so often when she is not wanted. The refusal of shared community with her sisters leaves her character alienated and flat. In contrast, Charlotte Lucas begins the novel as a stronger participant as Elizabeth’s closest friend, but her sudden marriage of convenience to a man she doesn’t love causes a permanent rift between herself and Elizabeth. At age twenty-seven, Charlotte already feels the effects of looming spinsterhood and takes the practical action of marrying to guarantee future security, although by doing so, she disconnects herself from her community of women. Kitty and Lydia's communication is far different from Jane and Elizabeth's since they connect on a much shallower level. The two youngest girls are only fifteen and sixteen years old and described as “silly,” whereas Jane and Elizabeth are described as the only seemingly well-bred people in their family. Mary is an enigma who keeps to herself and is mostly disconnected from both her family and broader social circles.

Readers never get to actually see the Bennet sisters before men enter the scene. We join their story with the arrival of Mr. Bingley and Mr. Darcy in town—two of the most eligible bachelors. It is as if we the readers are part of the men's entrance and are immediately caught up in Mrs. Bennet's husband-hunting mood. However, the women still exist in a fairly close sphere throughout the novel even as several of the sisters move toward marriage. During several moments in the novel, certain events cause ripples in the sisters’ relationships with each other. Elizabeth especially seems to struggle to keep things the same even as she realizes changes are imminent. One example early in the novel involves the girls’ mother. As part of her matchmaking efforts, Mrs. Bennet convinces Jane to ride on horseback to Mr. Bingley’s home during a rainstorm, effectively forcing her out of the circle of women. Elizabeth is annoyed by her mother’s insistence, and after receiving Jane’s note describing her illness resulting from being drenched,

Elizabeth, feeling really anxious, was determined to go to her, though the carriage was not to be had; and as she was no horsewoman, walking was her only alternative. She declared her resolution. ‘How can you be so silly,’ cried her mother, ‘as to think of such a thing, in all this dirt! You will not be fit to be seen when you get there.’ ‘I shall be very fit to see Jane—which is all I want.’ (Austen)Being kept away from her sister at this time would have been devastating for Elizabeth, and she refuses to stay home. She has no thought for the men she will invariably see at Netherfield; her only concern is for her sister. Here it becomes clear that Elizabeth is fighting to retain her close connection with Jane even as she sees her mother—under the guise of securing Mr. Bingley—pulling her away.

Perhaps the most obvious instance of male disruption in the novel is Mr. Collins’s visit. Since there are no Bennet sons, Longbourn estate is entailed, and the daughters have no claim to it. The girls’ mother either would not or could not understand the situation, and Austen writes that:

Jane and Elizabeth tried to explain to her the nature of an entail. They had often attempted to do it before, but it was a subject on which Mrs. Bennet was beyond the reach of reason, and she continued to rail bitterly against the cruelty of settling an estate away from a family of five daughters, in favour of a man whom nobody cared anything about. (Austen)Such is the first introduction to the famously ridiculous Mr. Collins, distant cousin and hopefully soon-to-be-husband to one of the Bennet sisters, who enters the scene with false modesty and the bestowal of unwanted attentions. Since it is his marriage to one of her daughters that will secure Longbourn, Mrs. Bennet changes her attention to one of her favorite pastimes: match-making. Mr. Collins is at first attracted to Jane since she is the oldest—and we are told prettiest—of the five daughters. However, Mrs. Bennet soon cures him of his attachment by strongly hinting at Jane’s expected engagement:

‘As to her younger daughters, she could not take upon her to say—she could not positively answer—but she did not know of any prepossession; her eldest daughter, she must just mention—she felt it incumbent on her to hint, was likely to be very soon engaged’ Mr. Collins had only to change from Jane to Elizabeth—and it was soon done—done while Mrs. Bennet was stirring the fire. Elizabeth, equally next to Jane in birth and beauty, succeeded her of course. (Austen)It is here that Austen so clearly displays the ridiculousness of many marriages. Mr. Collins, though himself a caricature, demonstrates the lack of concern that many men had for the women they were marrying; as soon as one became unavailable, the next pretty face would do just as well.

It goes without saying that this jumping from one sister to another would influence the relationships among the sisters themselves. Mr. Collins is introduced through his letter, which causes Mr. Bennet to describe in brutal terms the reality of the sisters’ positions as women: “’It is from my cousin, Mr. Collins, who, when I am dead, may turn you all out of this house as soon as he pleases’” (Austen). The promise of keeping their home and retaining financial security is possible for all of the Bennet women if one of the sisters marries the odious man, and he is all too aware of this fact. Leveraging his position, Mr. Collins proposes next to Elizabeth, who of course turns him down. And here begins a central disruption to our women’s community. We have not yet seen the last of Mr. Collins. Actually, he is the cause of the biggest change to Elizabeth’s circle of trusted friends. Early on in the novel, we realize that Charlotte and Elizabeth are extremely close friends and confidantes. It is safe to assume that if Elizabeth ever felt that she could not discuss something with Jane, she would instead discuss it with Charlotte, who in many ways, is like a second older sister. Charlotte’s personality fills the places for Elizabeth that are lacking in Jane’s friendship;

Charlotte sees things as they really are, whereas Jane always tries to see the best in everyone. For one critic, Breanna Neubauer, “Elizabeth and Charlotte’s best and most satisfying relationship, then, is with each other, if for no other reason than because, even more than to her beloved sister Jane, Elizabeth relates to Charlotte on a more sensible, intelligent level”. This fact helps to explain Elizabeth’s complete shock when she learns of Charlotte’s engagement to Mr. Collins. Elizabeth is dumbfounded:

‘Engaged to Mr. Collins! My dear Charlotte—impossible!’... ‘I see what you are feeling,’ replied Charlotte. ‘You must be surprised, very much surprised—so lately as Mr. Collins was wishing to marry you. But when you have had time to think it over, I hope you will be satisfied with what I have done.” (Austen)One can imagine Elizabeth’s dazed expression of disbelief as Charlotte continues her strange explanation, pointedly referring to Elizabeth’s own option to be selective in her choice of husband. Charlotte does not have that luxury.

I am not romantic, you know; I never was. I ask only a comfortable home; and considering Mr. Collins's character, connection, and situation in life, I am convinced that my chance of happiness with him is as fair as most people can boast on entering the marriage state.’Elizabeth quietly answered ‘Undoubtedly;’ and after an awkward pause, they returned to the rest of the family. Charlotte did not stay much longer, and Elizabeth was then left to reflect on what she had heard. It was a long time before she became at all reconciled to the idea of so unsuitable a match...She had always felt that Charlotte's opinion of matrimony was not exactly like her own, but she had not supposed it to be possible that, when called into action, she would have sacrificed every better feeling to worldly advantage. Charlotte the wife of Mr. Collins was a most humiliating picture! And to the pang of a friend disgracing herself and sunk in her esteem, was added the distressing conviction that it was impossible for that friend to be tolerably happy in the lot she had chosen. (Austen) Charlotte’s marriage to Mr. Collins shatters her relationship with Elizabeth; in marrying Mr. Collins, she loses Elizabeth’s respect, and she is also forced to move away from home. It is worthwhile to point out Charlotte’s reasons for marriage: “I am not romantic, you know; I never was.” Her low opinion of even the possibility of happiness in marriage is evident; she simply realizes that she must marry to survive.

Yet another instance of male interference in women’s circles is clearly displayed in the dishonesty and manipulation of Mr. Wickham. Not only does he succeed in convincing Elizabeth to believe his lies and nearly persuade herself to care for him, but he eventually elopes with Lydia, causing massive humiliation for the entire Bennet family. When Mr. Darcy tells her of Mr. Wickham’s true character, Elizabeth decides not to share the knowledge with her sisters. After Elizabeth hears the news of Lydia’s elopement with Wickham, she immediately regrets keeping the secret from her sisters: ‘When I consider,’ she added in a yet more agitated voice, ‘that I might have prevented it! I, who knew what he was. Had I but explained some part of it only—some part of what I learnt, to my own family! Had his character been known, this could not have happened. But it is all—all too late now.’ (Austen 345) Not only has Wickham literally torn apart the Bennet’s circle of women by eloping with Lydia, but he has also caused Elizabeth to willfully keep information from her other sisters. It is worth noting that Elizabeth is more upset at her own willful omission of the truth of Wickham’s character than she is at the initial news of her sister’s elopement. She is extremely upset that Lydia has potentially ruined her own reputation—and by extension the reputations of all her sisters. Through the entrance of Wickham and his influence over Lydia and Elizabeth, the connections among sisters are broken.

For Austen, a good woman is invariably a good sister, and a woman’s moral and emotional shortcomings are frequently signaled by her lack of sisterly concern.... Austen proposes that female-oriented relationships shape the heroine’s identity and are indicative of her moral and emotional worth. (Dobosiewics)Yes, Lydia physically and quite literally broke the bonds of sisterhood, but Elizabeth betrayed something even more important to the community of women—her sense of integrity in the way she communicates with her sisters.

Women in Pride and Prejudice communicate with each other differently than they communicate with others outside their circles. In Austen’s time,

Women were taught to view themselves as subordinate to, dependent upon, and at the service of men in their lives. One might speculate that the devaluation of sisterhood in patriarchy is caused by the fact that, to perpetuate male dominance, patriarchal ideology validates only male- oriented relationships. Not surprisingly, then, sororal ties have become marginalized, and consequently, unexamined, or misrepresented. (Dobosiewicz)Within scholarship considering women’s communication styles, we see several patterns emerge. As mentioned above, there is a high importance placed on integrity and honesty in women’s relationships with each other. Especially in Austen’s novels, the good relationships among women are grounded on mutual openness and encouragement. These relationships also focus on detailed story-telling and writing. Women shared important news with each other and embraced letters as a valuable form of communication when they were forced to be apart from other women, especially during the nineteenth century. Letter-writing plays a definite role in Pride and Prejudice as letters convey the most important plot points throughout the novel. Elizabeth and Charlotte correspond almost exclusively through letters after Charlotte’s marriage, and Elizabeth finds out about her sister Lydia’s elopement and the subsequent actions taken by her family through letters.

There are, however, also examples in the novel of women’s letters being quite the opposite of encouraging and honest. Mr. Bingley’s sister Caroline writes a letter to Jane in which she lies about his reasons for leaving town. Elizabeth immediately suspects Caroline of convincing her brother to leave, but the wording of her letter attempts to disguise the fact with false disappointment and the socially accepted request of further correspondence between herself and Jane:

‘I do not pretend to regret anything I shall leave in Hertfordshire, except your society, my dearest friend; but we will hope, at some future period, to enjoy many returns of that delightful intercourse we have known, and in the meanwhile may lessen the pain of separation by a very frequent and most unreserved correspondence. I depend on you for that.’ To these highflown expressions Elizabeth listened with all the insensibility of distrust. (Austen)Even as she writes a letter full of lies, Caroline Bingley asks for Jane’s continued “friendship” in the form of letters. Although she has broken the integrity of real friendship, she still asks Jane to continue this obvious surface appearance of it. Elizabeth’s strongest prejudice against Mr. Darcy does not stem mainly from her dislike of his wealth, status, or prideful attitude. Rather, she is infuriated by the fact that he separated Mr. Bingley from Jane. By destroying Jane’s chance at love and happiness, Mr. Darcy deeply hurts Elizabeth by extension. When Mr. Darcy first proposes to Elizabeth, her main reason for refusing him is this interference in her sister’s relationship with Mr. Bingley. In a fit of frustrated anger, Elizabeth asks him: “do you think that any consideration would tempt me to accept the man who has been the means of ruining, perhaps for ever, the happiness of a most beloved sister?” (Austen). Even if Elizabeth had wanted to accept Mr. Darcy’s first proposal, it can be assumed that she would have refused on principle because he had hurt her sister. The bond between them was stronger than anything she would gain through marriage.

If we view the women’s community in this novel as utopia, then it is one that the men in some ways want to enter. Mr. Darcy in particular goes through several phases of his relationship with Elizabeth— pride, prejudice, denial, love, and eventually remorse. Strangely enough, when he does explain himself to Elizabeth, it is through a letter. He spends an entire night composing a lengthy letter that succeeds in convincing Elizabeth of his integrity and moral character. In order for Mr. Darcy to gain limited entrance into this “utopia,” he uses a woman’s form of communication—the emotional and detailed letter which takes up nearly an entire chapter. He writes the letter because he sees it as his only chance to redeem himself in Elizabeth’s eyes. He tells her the full story behind his actions and also the truth of Wickham’s conduct in passionate and personal words that Elizabeth accepts far more readily than his initial angry explanation. It is through this letter that Elizabeth begins to change her thinking toward Mr. Darcy: “Mr. Darcy's letter she was in a fair way of soon knowing by heart. She studied every sentence; and her feelings towards its writer were at times widely different” (Austen). By displaying his honesty and vulnerability in a letter—while simultaneously defending his honor—, Mr. Darcy allows Elizabeth the time and consideration to rethink her feelings toward him. She trusts him more through the letter than she ever did when speaking directly to him. However, Mr. Darcy does not fully want to be invited into the womanly “utopia” any more than Elizabeth wants to allow him in. In fact, it is impossible for him to enter her community even if he curiously or half-heartedly seeks entrance; his very presence would transform the group whether he sought the change or not. It is far more plausible that Darcy would eagerly take Elizabeth out of her utopian women’s community if his first marriage proposal is any indication when he asks her: “Could you expect me to rejoice in the inferiority of your connections? –to congratulate myself on the hope of relations, whose condition in life is so decidedly beneath my own” and later in his letter when he explains that “The situation of your mother’s family, though objectionable, was nothing in comparison to the total want of propriety so frequently, so almost uniformly betrayed by herself, by your three younger sisters, and occasionally even by your father” (Ch. 34). His focus on her “mother’s family” and the embarrassment caused by the other women in her family make it clear that he believes he is better for her. In a way, marriage to him would be rescuing her from the humiliation of her community of women. Darcy’s perceptions of women are immutable and severe; it takes him weeks to admit his love for Elizabeth because he believes she is too far beneath him to warrant serious attention.

Earlier in the novel, Elizabeth and Darcy take part in a conversation debating what a woman must achieve to be truly “accomplished.”

‘All this she must possess,’ added Darcy, ‘and to all this she must yet add something more substantial, in the improvement of her mind by extensive reading.’ ‘I am no longer surprised at your knowing only six accomplished women. I rather wonder now at your knowing any.’ ‘Are you so severe upon your own sex as to doubt the possibility of all this?’ ‘I never saw such a woman. I never saw such capacity, and taste, and application, and elegance, as you describe united.’ (Austen 58)Here, Elizabeth is defending women although Mr. Darcy attempts to tell her that she is not giving women enough credit for their talents. She refuses to accept his definition of what makes a woman accomplished. Instead she points out to him the ridiculousness of that list. However, this list of accomplishments was originally brought up by none other than Caroline Bingley, who tells Mr. Darcy that:

No one can be really esteemed accomplished who does not greatly surpass what is usually met with. A woman must have a thorough knowledge of music, singing, drawing, dancing, and the modern languages, to deserve the word; and besides all this, she must possess a certain something in her air and manner of walking, the tone of her voice, her address and expressions, or the word will be but half-deserved. (Austen)This list is a veritable buffet of nineteenth-century stereotypes and expectations of women. Elizabeth knows that the list is superficial and that Caroline Bingley is simply trying to parade herself in front of Mr. Darcy and receive his approbation.

Miss Bingley is just one example of how Austen cleverly contrasts differences in how women—especially sisters—relate to one another. Mr. Bingley has another sister, a woman only ever called by her husband’s name—Mrs. Hurst. The Bingley sisters are only described as “fine women, with an air of decided fashion” (Austen). These external characteristics are all we need to know about these two women who are only focused on the external and have no real depth of character. It is safe to assume that the only true connection these two sisters have with each other is the combined ability to convince their brother to act according to their will. When Darcy mentions that Jane is pretty, but smiles too much, Austen gives us the following information about the two Bingley sisters:

Mrs. Hurst and her sister allowed it to be so—but still they admired her and liked her, and pronounced her to be a sweet girl, and one whom they would not object to know more of. Miss Bennet was therefore established as a sweet girl, and their brother felt authorized by such commendation to think of her as he chose. (Austen)Initially, Mr. Bingley is convinced to care for Jane because of encouragement from his sisters; however, he is just as easily swayed by their opinions when they (along with Mr. Darcy) convince him that she doesn’t care for him. It is not unbelievable to view Caroline Bingley and Mrs. Hurst as a sister set of foils to Jane and Elizabeth. They are an example of sisterhood gone awry and potential community wasted.

In Austen’s first two novels especially, she “creates a pair of devoted sisters who are superior to the other members of their family and complementary in temperament. The love quests of the sisters intertwine, and the resolutions to both stories ensure the happiness not only of marriage but of sisterhood” (McNaron 56). If we do not quite believe that the heroine’s marriages ensure true happiness, then at least we can see that they do promise that the sisters will not be completely separated. Austen promises at the end of Pride and Prejudice that “[Mr. Bingley] bought an estate in a neighbouring county to Derbyshire, and Jane and Elizabeth, in addition to every other source of happiness, were within thirty miles of each other” (Austen). The sisters’ continuing closeness is now brought to literal distance—thirty miles—so that even after marriage, their sisterhood is not destroyed. Unfortunately, Austen ends the novel before readers can see what Jane and Elizabeth’s relationship was like after their marriages, but we can quite accurately guess that though it was changed, they were still able to spend many happy hours at each other’s homes. This is quite preferable to what often happened after marriages when sisters were separated by hundreds of miles, which at the time meant that they may never see each other again.

Jane and Elizabeth’s strong relationship holds steady during and after their separation. Happily, the two of them are able to marry for love, which at the time was a luxury, as Charlotte points out to her “romantic” friend. Perhaps their story represents an alternative ending that Austen imagined for herself and Cassandra had life been different for them. One thing we can know for sure, Austen believed that the bond between sisters is sacred and more enduring than marriage.

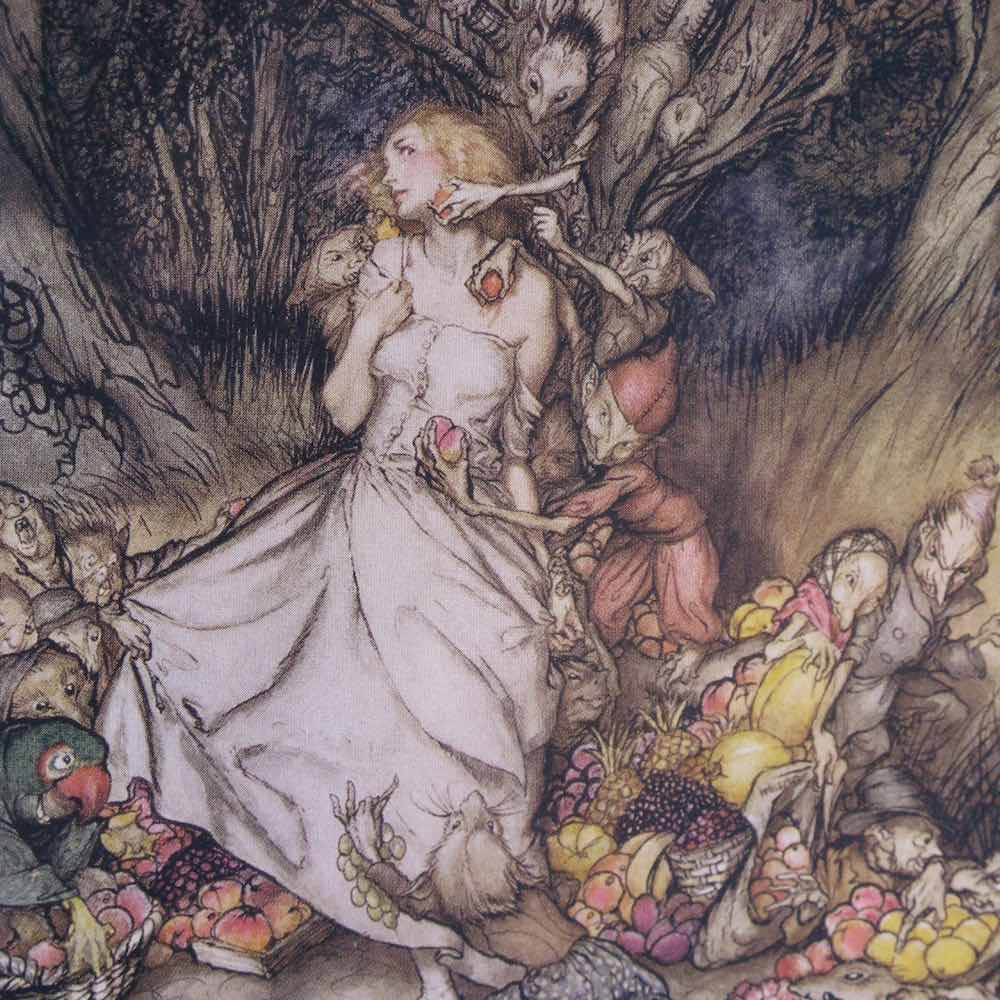

The theme of strength found through sisterhood is common in all three works discussed here—Pride and Prejudice, Little Women, and “Goblin Market.” The central characters are quite literally sisters within the same families; the Bennet sisters, March sisters, Lizzie and Laura all share this bond. One of the most striking characteristics across the three works is that of the biographical similarities among the authors and their real-life sisters. As mentioned previously, Jane and Cassandra Austen were inseparable for all of Jane’s life. It is to Cassandra that we owe any knowledge of her sister, and the small amount we do have is what she considered of too little importance to gain any notice. However, the strong sisterly bond did not only influence Austen. Alcott based her novel on the childhood experiences she shared with her own three sisters, and Rossetti’s somewhat complicated relationship with her older sister influenced nearly everything she ever wrote, specifically her sister poems.

Part Three, Little Women’s Utopian Community, can be read here.

*****

3 comments

[…] is part three of the essay. Part two can be found here and part one can be found […]

Women's Circles Broken - Part Three

As well as the comment by AdamQ pointing out one incorrect instance from P&P, Meagan Hanley is also incorrect in saying that Lizzy does not tell her sisters of what she learns of Mr Wickham’s less than stellar character. She tells Jane. She even tells Jane about his attempted elopement with Georgiana Darcy.

The two sisters together decide not to tell the rest of the family, not just the three silly younger sisters. We know Lydia would have totally ignored the information anyway, but Mr Bennet may have listened and been able to curb Lydia’s inappropriate behaviour with the officers and kept her home from Brighton.

Lizzy and Jane together decide not to inform everyone, so the sororal closeness between Lizzy and Jane is constant, even here.

Anonymous

" Mr. Bingley has another sister, a woman only ever called by her husband’s name—Mrs. Hurst. "

No, she is named as Louisa a number of times by both Caroline and Charles Bingley.

Anonymous

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.