Assessing Male Eligibility: A Jane Austen Reading Aloud Test

How do the young men and women in Jane Austen’s novels get on intimate terms? They talk, sing, play cards, go for walks, put on plays, have meals and picnics and dance together. They also read aloud to each other.

Jane Austen transforms the quite commonplace interaction of reading aloud, a regular feature of Georgian domestic life, into a finely tuned literary device. Reading aloud serves as a meeting ground for the sexes to explore emotional, social, cultural and intellectual compatibility. Reading to others becomes nothing less than a test of character.

The characters most likely to do the reading? Eligible bachelors. While the male characters read aloud, the female characters listen. From Sense and Sensibility to Persuasion, male characters’ reading style and reading choices are put in the frame. And the reading takes place in the women’s domain: at home, in the parlour or drawing room.

The women listen to the men’s reading, but not passively. They respond; they comment; and sometimes even interrupt the reading and the reader. Instead of “the male gaze”, it’s more a case of “the female listening ear” as women react to and assess the male reading voice.

Mansfield Park: Henry Crawford’s captivating reading of Shakespeare

Let’s start with Mansfield Park which contains arguably the greatest ‘reading aloud’ scene in literature.

The cad Henry Crawford has set his sights on Fanny, who secretly loves Edmund, her kind and thoughtful cousin. She shows no signs of wavering and appears quietly but firmly inured to Henry’s advances. That is, till Henry starts to read aloud from Shakespeare’s Henry VIII after dinner one evening. At last Fanny’s reserve appears to break down. This is not a romantic experience, or a flirtatious encounter. It is something far more visceral. The full-on seductive power of Crawford’s reading creates a charged energy in the room. Crawford is dangerous, his charm and charisma nudging Fanny towards capitulation:

“…she was forced to listen; his reading was capital, and her pleasure in good reading extreme. To good reading, however, she had been long used: her uncle read well, her cousins all, Edmund very well, but in Mr. Crawford’s reading there was a variety of excellence beyond what she had ever met with. The King, the Queen, Buckingham, Wolsey, Cromwell, all were given in turn; for with the happiest knack, the happiest power of jumping and guessing, he could always alight at will on the best scene, or the best speeches of each; and whether it were dignity, or pride, or tenderness, or remorse, or whatever were to be expressed, he could do it with equal beauty.”

Austen lingers on the scene and describes the full effect of Crawford’s mesmerising reading, as Fanny sits, transfixed:

“how she gradually slackened in the needlework, which at the beginning seemed to occupy her totally: how it fell from her hand while she sat motionless over it, and at last, how the eyes which had appeared so studiously to avoid him throughout the day were turned and fixed on Crawford—fixed on him for minutes, fixed on him, in short, till the attraction drew Crawford’s upon her, and the book was closed, and the charm was broken.”

Here is reading aloud — or more accurately, listening to a reading — as deeply perilous for the heroine. Crawford understands how to deploy his reading skill and for what ends. It is not just Fanny who is at risk: neither Austen nor we seem safe from Crawford’s verbal prowess.

Sense and Sensibility: Edward Ferrar’s indifferent reading of William Cowper

In Sense and Sensibility, a reverse dynamic is at play as we listen in to a conversation discussing a would-be suitor’s flawed reading abilities. The excessively romantic Marianne misinterprets Edward Ferrars’ lacklustre reading style, which she regards as unfeeling, appearing to show a disregard of the poetry he has been asked to read. These failures of character would make him, in Marianne’s assessment, an unworthy man for Elinor (her more ‘sensible’ and practical sister) even though Marianne admits that Elinor seems unfazed:

“’Oh! mama, how spiritless, how tame was Edward’s manner in reading to us last night! I felt for my sister most severely. Yet she bore it with so much composure, she seemed scarcely to notice it. I could hardly keep my seat. To hear those beautiful lines which have frequently almost driven me wild, pronounced with such impenetrable calmness, such dreadful indifference!”

However, Mrs. Dashwood’s measured response to Marianne shows her better understanding of Ferrars’ character: “He would certainly have done more justice to simple and elegant prose. I thought so at the time; but you would give him Cowper.” With the right material to read aloud, the subtext reads, he would have shown himself to be the perfect partner for Elinor.

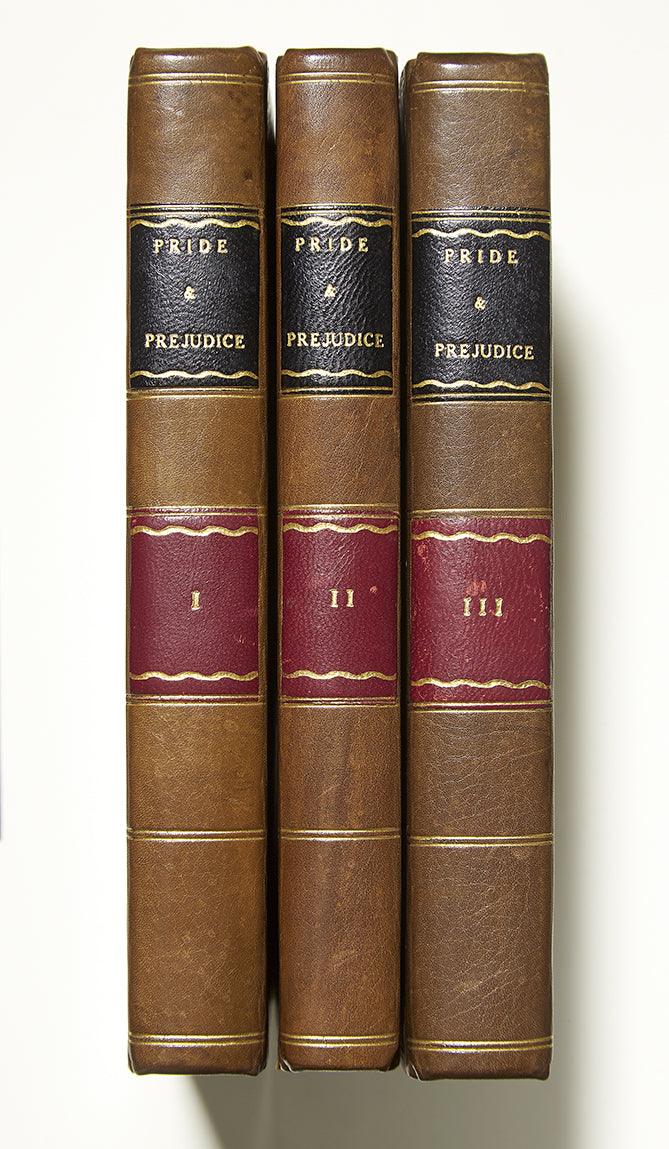

Pride and Prejudice: Mr Collins chooses James Fordyce's Sermons

As for Pride and Prejudice, though we learn early on of Mr Darcy’s splendid library at Pemberley, he doesn’t give Elizabeth an opportunity to assess his reading aloud skills for herself. Tellingly, we only witness him reading to himself. To Elizabeth and the reader, it is yet another sign of his aloofness. A man of few words, his quietness opens up space for misjudging his real character. You might say his silent reading speaks volumes.

The odious and self-important Mr Collins is more forthcoming when he is invited to read aloud to the Bennet girls, but only up to a point. Eschewing novels as something he would never read (a lovely in-joke for us, the readers of P&P, especially those reading it aloud) he turns to a book of sermons by James Fordyce, a conventional and serious choice worthy of the clergyman that he is. Together with his choice of book, his style of reading — and the Bennet sisters’ responses —illuminates not only his own pompous and condescending tendencies but also, in Lydia’s careless and rude response, her impetuosity and disregard for civility and good manners. He reads “with very monotonous solemnity” provoking Lydia to interrupt but her more polite sisters Jane and Elizabeth try to get her to “hold her tongue”. After all, reading circle etiquette demands an attentive audience.

Emma: Mr Martin surprises with “Elegant Extracts”

A male character’s attitude to reading is again the focus of a scene in Emma, but rather than it elucidating personal values or feelings, social class is in the frame. The Martins are a local farming family, and friends of Harriet (who is not the ‘social equal’ of Emma but whom Emma aspires to improve). Emma is quick to assume the Martin family to be “coarse and unpolished”. Wishing to find out more about Mr Martin, for whom Harriet appears to show an inclination, Emma poses a question of Harriet about literary tastes, a question she puts in the negative: “Mr. Martin, I suppose, is not a man of information beyond the line of his own business? He does not read?” The first part of Harriet’s answer seems to confirm that his reading is ‘business’ related, with Mr. Martin a serious though solo reader,: “He reads the Agricultural Reports, and some other books that lay in one of the window seats—but he reads all them to himself.”

But the second part of Harriet’s answer is a revealing one, at least it would be if Emma were not so blinkered as to ignore what it signified. Harriet relates how she was present on occasions when Mr Martin would read aloud to his family, “sometimes of an evening, before we went to cards, he would read something aloud out of the Elegant Extracts, very entertaining.” The Elegant Extracts, a popular anthology of prose writing which Austen’s readers would have known or owned themselves, marks Mr Martin out as a man of good taste and solid cultural aspirations as well as showing that he was a fluent, even accomplished reader and performer (“very entertaining”), keen to oblige his family and guests. Though Emma remains blind to Mr Martin’s good qualities, this anecdote is to stand him in good stead.

Northanger Abbey: Henry Tilney reads Udolpho to himself

Northanger Abbey, the novel most overtly about reading, with its critique of the gothic novel and the naïve over-active imagination of the heroine, Catherine Morland, makes a joke of (a man) depriving a female character of the opportunity for communal reading. Henry Tilney, having pledged to read the gothic novel Udolpho to his sister, teasingly admits to Catherine that he broke his promise because of his “eagerness to get on”, the implication being that the novel’s grip on the reader is so strong that it leads to a loss of self-control, even selfishness, “I am proud when I reflect on it, and I think it must establish me in your good opinion,” Henry jokes. Austen shows us by this brief remark that Henry understands the entertainment value of these types of books, and plants evidence that he will not deal too harshly with Catherine’s misguided imagination later in the novel.

Persuasion: Captain Wentworth reads the Navy List

In Persuasion it is what Captain Wentworth chooses to read aloud, rather than the manner in which he reads it that is so illuminating. On meeting Anne again, who had once rejected him, Wentworth is drawn into conversation with the Miss Musgroves on the naval life and they are curious to know of the ships that he has commanded. Presented with the Navy List, Wentworth fondly reads aloud the details of the ship of which he had been commander:

“[he] could not deny himself the pleasure of taking the precious volume into his own hands and once more read aloud the little statement of her name and rate, and present non- commissioned class”.

Wentworth’s commentary that the ship “had been one of the best friends man ever had”, serves as subtext that the Captain had displaced his failed relationship with Anne by a different form of friendship and way of life. The Navy List as material to read aloud is a surprising choice for our hero. This is no Cowper (ill matched to Edward Ferrars’ character), no moral sermon (in the case of Mr Collins), no Shakespeare (that had showed off the range of Mr Crawford’s reading skills) or Elegant Extracts (though if Mr Martin had thought to read out his Agricultural Reports it might have been close). Not even written in sentences, this is a list of facts yet for all that entails it is as revealing of character as these other examples.

So — reading aloud as an act of seduction and intimacy, as a test of character and taste and as an indicator of values and compatibility. A powerful tool! Perhaps we Janeites can campaign for a renaissance of domestic reading aloud — especially the reading aloud of Jane’s novels?

In the next part of this Jane Austen Read Aloud series we’ll look at Jane’s own skill in reading aloud, how her books were written to be heard and how it helped hone her craft…

In the second part of this article, which you can now read at this link, Liz will explore the reading aloud habits of Austen herself. READ PART TWO

Liz Ison is a lifelong Jane Austen fan. Liz studied English literature and social science at Cambridge, before training as a speech and language therapist. She has a doctorate from UCL for research into childhood speech and literacy development. Liz trained with The Reader and runs shared reading groups, in person and online, where everything is read aloud. She has edited an anthology “A Poem to Read Aloud for Every Day of the Year”, published 14 Sept 2023. She lives in London. Y ou can find Liz on Instagram @liz.ison

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.