Sense and Sensibility

Sense and Sensibility

By Jane Austen

Introduction by Margaret Anne Doody

Review by Ellen Moody

I was delighted when Laurel of

Austenprose asked me to join her in writing reviews of the recent reprint of the Oxford standard editions of Austen’s novels. I’d get to gaze at the different covers, read introductions, notes, appendices, and if any were included, illustrations. As you might have guessed, I’m one of those who partly chooses to buy a book based on its cover. I enjoy introductions (occasionally more than the story they introduce), get a kick out of background maps and illustrations, and especially ironic notes.

Looking into the matter I discovered I’d have to sleuth what if anything was the difference between these new reprints and the earlier reprints of James Kinsley’s 1970-71 edition, from which all the subsequent Oxford texts have been taken. Why after examining the early texts did Kinsley made the choice to reprint R. W. Chapman’s 1923 edition of Austen’s novels with some emendations? Hmm. My curiosity made me unable to resist checking the Oxfords against the other editions of Austen’s novels I own. In the case of Austen’s

Sense and Sensibility, a novel I first read when I was 13 and the one closest to my heart, I own 14 different editions and reprints, and French and Italian translations.

The more cynical and less devoted reader of Austen may well say, wait a minute here. What would be the point or interest, since probably the differences in the texts themselves would be miniscule, the paratexts just the sort of thing Catherine Morland would have skipped, and this upsurge of proliferating books simply the result of a highly competitive marketplace. But that’s the point. We can ask why provide all this if the goal is to produce an inexpensive handy text and the motive profit? The answer comes back that Austen’s novels are at once high status, beloved, and best-selling texts which keep selling because they’re best-selling books. They have highly diverse and conflicting groups of (let us call them) consumers. So in order not to offend and to persuade as many readers as possible to buy at least once or yet again, publishers are driven to produce books which are informative and pleasing, accurate and accessible—and up-to-date. Since the reprints cover more than a quarter of a century, we may watch different introducers struggling to present their respective agendas, which, like the changes in the covers of the books, reflect the ever-changing climate of a surprizingly stormy Austenland.

We also had more than the famous six books because since 1980 Oxford had chosen to accompany

Northanger Abbey with

Lady Susan, The Watsons, and

Sanditon, Austen’s lesser-known novels (the first epistolary, the last two unfinished). Laurel and I had an intriguing journey ahead of us. We agreed we would form sister reviews, each one a counterpart to the other. A reading of

Laurel's review will give a good overview to the book.

I agree with Laurel that the 2008 reissue of the Oxford’s 2004 edition of Kinsley’s

Sense and Sensibility is a good buy. It avoids extremes, or is a half-way house between series which just reproduce an unannotated text, only sometimes with a brief “Afterword” essay2; and series which may overload readers with an apparatus in the back of contemporary documents, recent critical essays (some the result of this year’s fashions in academia), and contain aggressive overly abstract introductions by writers who seem to take a downright hostile stance to the texts and most of its readers3.

The introductory essay by Margaret Anne Doody is brilliant, eloquent, and comprehensive; since 2004 the Oxford has included two appendices by Vivien Jones who wisely chose to explain two kinds of pivotal concerns and happenings in all Austen’s novels: Appendix One explains the rank and social status of the characters, and Appendix Two, the different dances included in her novels and how they can function. Claire Lamont has mostly improved on and rewritten the explanatory notes from the previous edition: the new ones are fuller, and more contemporary texts are cited. The method is to give the reference by page number and use an asterisk; this makes for a speedy flip back and forth4.

So much for complementarity. Laurel has summarized the topics of Doody’s introduction and interesting items cited in the bibliography, discussed the all- too-short life, and the role of chaperon in a young genteel woman’s life (as suggested by the appendix on dancing), and left to me the not unimportant business about exactly what is presented to us as Jane Austen’s written extant novel. To this I’ll add a little on the covers, and brief information on the 5 available film adaptations of the novel.

To wit, we do not have in whole or part any manuscript version by Austen of

Sense and Sensibility so we cannot know for sure what her text of this novel was like. As they do today, printing houses then had styles of their own, and no text was at all sancro-sanct from changes in punctuation, grammar, paragraphing and the like. Of the versions of S&S published in Austen’s lifetime, the first published in 1811 was sold out. Austen rejoiced, and in 1813 there was a second. Austen was actively involved in the production of both; she proof-read the first, but, alas, apparently not the second, and errors of all sorts have been found in the 1813 text. On the other hand, Austen made small revisions of this 1813 text so those are her last emendations in print. Here we have to remember the painful truth that Jane Austen died young and didn’t have much chance to have second thoughts for her book: she was producing the final copies for all 4 she saw into print and writing all six (plus perhaps a seventh, Sanditon). A very busy lady indeed and then mortally ill.

Over the 19th century errors crept into the many reprints of Austen’s books; and in 1923 R.W. Chapman sat down to produce scrupulously accurate scholarly texts which were the equivalent of what were printed for very high status male authors; he followed the standards of his time, which included discreet corrections of grammar, punctuation and paragraphing. For

Sense and Sensibility he chose the 1813 edition after correcting it, and it’s Chapman’s text that Kinsley studied, emended somewhat and is the basis for all Oxfords afterwards. Recently though it’s been asserted that Chapman over-corrected and so polished Austen’s text that we lose flavor, tone, and something of the colloquial voice of Austen; and in the 2003 new Penguin edition, Kathryn Sutherland has taken the rare step of using the 1811 text as her basis. Did Chapman really alter the spirit of Austen’s books? Yes and no. Sutherland’s edition gives us a less polished, more sparsely punctuated text.

It should be admitted, as with introductions to texts, this is something of an agenda fight. Kathryn Sutherland, Claudia Johnson (editor of the recent Norton edition), and others feel the perceived picturesqueness & tea-and-crumpets quaint feel of Chapman’s original Oxfords helped sustain a kitsch and elitist view of Austen. It’s also a turf fight: the publishers of these texts need their choices to be respected to gain the full Austen readership.

But there’s something more here too. Austen did change some actual wording in the 1813 edition. Now it’s sometimes true the author’s first text was the superior one; sometimes the last corrected one is. It’s a matter of judgement and taste. What’s important is the text be not bowdlerized. In 1813 Austen cut a second sentence that appears in the 1811 text: in 1811 at the Delaford Abbey picnic, the narrator repeats the rumor that Colonel Brandon has a “natural daughter” that Mrs Jennings’s brief mention made public. We are told Mrs Jenning’s statement so

“shocked the delicacy of Lady Middleton that in order to banish so improper a subject as the mention of a natural daughter, she actually took the trouble of saying something herself about the weather” (I:3).

Strangely, for all Sutherland complaints about Chapman, he did include the 1811 sentence in his reprint of the 1813 text. He simply intelligently made a judgement call and put it back. Alas, somewhere along the line this offending sentence was omitted from all editions strictly based on the 1813 text, and now appears only in the footnotes to all, including this latest 2008 Oxford! What bothers me is in the notes most scholars repeatedly refuse to recognize the obvious, that Austen deleted the sentence because it was too frank. Instead we get supersubtle interpretations that Austen removed the passage because she didn’t want the situation to be tactfully covered up. But how could it be, since Mrs Jennings has let the cat out of the bag, and this is one of those many secrets Austen’s Mr Knightley tells us is just the sort of thing everyone knows.

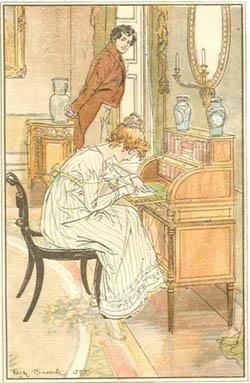

On to the covers. There is a long custom of picking pictures of two upper class women (often sisters) standing or sitting close together for the cover of S&S. This began in the first popular editions of the 19th century, Bentley’s 1833 volume where we see Lucy and Elinor walking together. It’s seen in James Kinsley’s choice of a Hugh Thomson illustration of the very moment Marianne sees Willoughby at Lady Middleton’s assembly. Entirely typical of just every choice I’ve seen is how Thomson’s psychological depiction is wholly inadequate. Pair after pair of women are chosen whose faces are expressionless, but whose credentials, as visibly upper class, fleshly (this once having been a sign of high rank), white, elegant dressers, are unassailable.

For example,

Sara Coleridge with Edith May Warner by Edward Nash [1820], the 1980 Oxford cover;

Ellen & Mary McIlvane by Thomas Sully [1834], the 2003 New Penguin cover. These latest Oxfords differ only in preferring to focus on an enlarged detail of the two women, something Laurel tells me is fashionable in covers. An earlier version may be found in a 1983 Bantam,

Charlotte and Sarah Hardy by Thomas Lawrence (1801)

No one disputes the centrality of a pair of sisters as central to the novel (and primal to Austen as in all her novels we find them), but I am heterodox enough to declare that as a reader of Austen, I’m of the party who feels if we are to have two women, let us have either genuinely effective images, or one of the many effective stills from the recent movies, as in covers of the 1995 Signet and 1996 Everyman.

Even a landscape redolent of picturesqueness or some pivotal point in the story of the Dashwoods would suffice. This latter choice is uncommon, although the 2002 Norton appropriatetly chose

Devonshire Landscape by William Payne (c. 1780).

What I particularly liked about Margaret Doody’s essay in this new Oxford is she demonstrates the plot-design, climaxes, and much of the text of the novel is as much about social life, women’s relationship with other women, economic injustice, and aesthetic hypocrisies and affectation as it is a love story.

Paperback: 384 pages

Publisher: OUP Oxford; Rev. Ed. / edition (17 April 2008)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0199535574

ISBN-13: 978-0199535576

RRP: £4.99

Ellen Moody, a Lecturer in English at George Mason University, has compiled the most accurate calendars for Jane Austen's work, to date. She has created timelines for each of the six novels and the three unfinished novel fragments. She is currently working on a book,

The Austen Movies. Visit her

website for further Austen related articles.

Sense and Sensibility

Sense and Sensibility On to the covers. There is a long custom of picking pictures of two upper class women (often sisters) standing or sitting close together for the cover of S&S. This began in the first popular editions of the 19th century, Bentley’s 1833 volume where we see Lucy and Elinor walking together. It’s seen in James Kinsley’s choice of a Hugh Thomson illustration of the very moment Marianne sees Willoughby at Lady Middleton’s assembly. Entirely typical of just every choice I’ve seen is how Thomson’s psychological depiction is wholly inadequate. Pair after pair of women are chosen whose faces are expressionless, but whose credentials, as visibly upper class, fleshly (this once having been a sign of high rank), white, elegant dressers, are unassailable.

For example, Sara Coleridge with Edith May Warner by Edward Nash [1820], the 1980 Oxford cover; Ellen & Mary McIlvane by Thomas Sully [1834], the 2003 New Penguin cover. These latest Oxfords differ only in preferring to focus on an enlarged detail of the two women, something Laurel tells me is fashionable in covers. An earlier version may be found in a 1983 Bantam, Charlotte and Sarah Hardy by Thomas Lawrence (1801)

No one disputes the centrality of a pair of sisters as central to the novel (and primal to Austen as in all her novels we find them), but I am heterodox enough to declare that as a reader of Austen, I’m of the party who feels if we are to have two women, let us have either genuinely effective images, or one of the many effective stills from the recent movies, as in covers of the 1995 Signet and 1996 Everyman.

On to the covers. There is a long custom of picking pictures of two upper class women (often sisters) standing or sitting close together for the cover of S&S. This began in the first popular editions of the 19th century, Bentley’s 1833 volume where we see Lucy and Elinor walking together. It’s seen in James Kinsley’s choice of a Hugh Thomson illustration of the very moment Marianne sees Willoughby at Lady Middleton’s assembly. Entirely typical of just every choice I’ve seen is how Thomson’s psychological depiction is wholly inadequate. Pair after pair of women are chosen whose faces are expressionless, but whose credentials, as visibly upper class, fleshly (this once having been a sign of high rank), white, elegant dressers, are unassailable.

For example, Sara Coleridge with Edith May Warner by Edward Nash [1820], the 1980 Oxford cover; Ellen & Mary McIlvane by Thomas Sully [1834], the 2003 New Penguin cover. These latest Oxfords differ only in preferring to focus on an enlarged detail of the two women, something Laurel tells me is fashionable in covers. An earlier version may be found in a 1983 Bantam, Charlotte and Sarah Hardy by Thomas Lawrence (1801)

No one disputes the centrality of a pair of sisters as central to the novel (and primal to Austen as in all her novels we find them), but I am heterodox enough to declare that as a reader of Austen, I’m of the party who feels if we are to have two women, let us have either genuinely effective images, or one of the many effective stills from the recent movies, as in covers of the 1995 Signet and 1996 Everyman.

Even a landscape redolent of picturesqueness or some pivotal point in the story of the Dashwoods would suffice. This latter choice is uncommon, although the 2002 Norton appropriatetly chose Devonshire Landscape by William Payne (c. 1780).

What I particularly liked about Margaret Doody’s essay in this new Oxford is she demonstrates the plot-design, climaxes, and much of the text of the novel is as much about social life, women’s relationship with other women, economic injustice, and aesthetic hypocrisies and affectation as it is a love story.

Paperback: 384 pages

Publisher: OUP Oxford; Rev. Ed. / edition (17 April 2008)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0199535574

ISBN-13: 978-0199535576

RRP: £4.99

Ellen Moody, a Lecturer in English at George Mason University, has compiled the most accurate calendars for Jane Austen's work, to date. She has created timelines for each of the six novels and the three unfinished novel fragments. She is currently working on a book, The Austen Movies. Visit her website for further Austen related articles.

Even a landscape redolent of picturesqueness or some pivotal point in the story of the Dashwoods would suffice. This latter choice is uncommon, although the 2002 Norton appropriatetly chose Devonshire Landscape by William Payne (c. 1780).

What I particularly liked about Margaret Doody’s essay in this new Oxford is she demonstrates the plot-design, climaxes, and much of the text of the novel is as much about social life, women’s relationship with other women, economic injustice, and aesthetic hypocrisies and affectation as it is a love story.

Paperback: 384 pages

Publisher: OUP Oxford; Rev. Ed. / edition (17 April 2008)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0199535574

ISBN-13: 978-0199535576

RRP: £4.99

Ellen Moody, a Lecturer in English at George Mason University, has compiled the most accurate calendars for Jane Austen's work, to date. She has created timelines for each of the six novels and the three unfinished novel fragments. She is currently working on a book, The Austen Movies. Visit her website for further Austen related articles.

1 comment

Willett Amie

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.