The Subscription Library and the Rise of Popular Fiction

I have received a very civil note from Mrs. Martin, requesting my name as a subscriber to her library which opens January 14, and my name, or rather yours, is accordingly given. My mother finds the money. May subscribes too, which I am glad of, but hardly expected. As an inducement to subscribe, Mrs. Martin tells me that her collection is not to consist only of novels, but of every kind of literature, &c. She might have spared this pretension to our family, who are great novel-readers and not ashamed of being so; but it was necessary, I suppose, to the self-consequence of half her subscribers.

-Jane Austen to Cassandra (December 18, 1798)

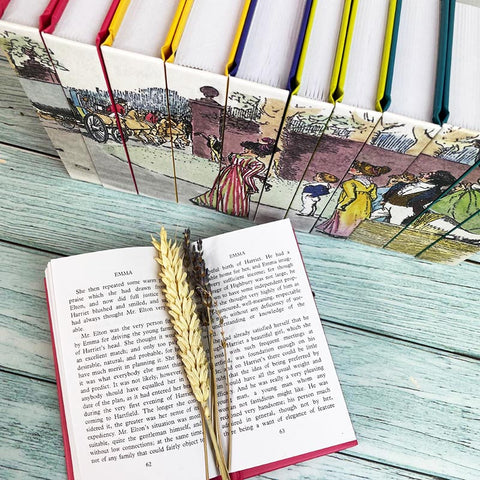

In a time before television and recorded music, live entertainment, sewing and reading provided the main occupation for leisurely hours. While a great house or estate like Pemberly might boast a well endowed library most middle class families would have been hard pressed to expand their private collections at a pace well able to keep up with the family's demands. Books were an expensive luxury in Austen's day-- Sir Walter Scott's three volume novels were sold at the exorbitant rate of 31s. 6d (or close to £90 in today's currency). With the growing middle class gaining previously unheard of free time, there was a great demand for new works of entertainment-- hence the popularity of the "Novel", an only recently created genre, with the publication of Robinson Crusoe in 1719. Into this void came the idea of a circulating or subscription library. By definition, it is "a library that is supported by private funds raised by membership fees or endowments. Unlike a public library, access is often restricted to those who are members". For as little as 1£, 11s, 6d. per year, one could purchase a first class library subscription entitling them to "10 volumes at a time in town and 15 in the country," well supplying a household of young ladies, like the Bennets, with all the delightful reading they could require (bear in mind that most novels at the time were published in three volume sets). Second and third class subscriptions could also be purchased at a lower cost, with fewer benefits.

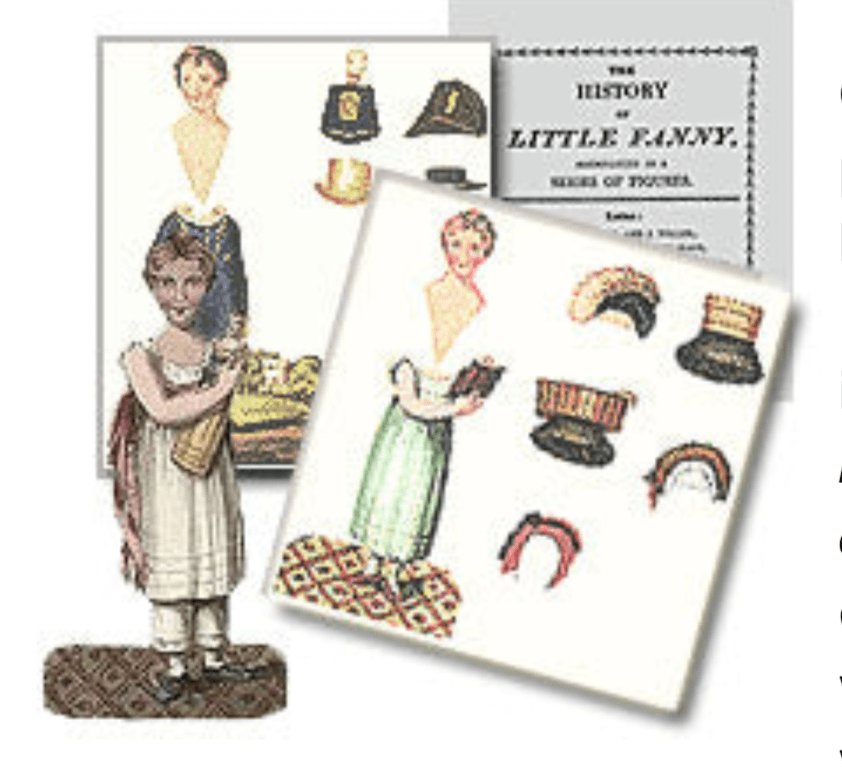

A library, such as the one Lydia visits in Brighton, might also serve as a sort of gift shop for its clientele, containing such charming items as brooches, shawls, parasols, gloves and fans, all sold for their customer's enjoyment. Libraries were not, as they are today, heralded as wonderful institutions bringing literacy to the masses. Far from it; outspoken critics to the new availability of books and the following trend of writing to please the "masses" claimed that "the pressures toward literary degradation which were exerted by the booksellers and circulating library operators in their efforts to meet the reading public's uncritical demand for easy vicarious indulgence in sentiment and romance" caused "a purely quantitative assertion of dominance" by female authors and readers, and by the gothic romance genre. Namely, that, "circulating libraries vulgarized literature, by pandering fiction to women, servants, and other people who had previously been excluded from reading by the high cost of books or by illiteracy."* No wonder Jane Austen offers such a strong defense to her chosen mode of expression. In Northanger Abbey the topic of novels arises, and in a rare outpouring of personal feeling, writes:

The progress of the friendship between Catherine and Isabella was quick as its beginning had been warm, and they passed so rapidly through every gradation of increasing tenderness that there was shortly no fresh proof of it to be given to their friends or themselves. They called each other by their Christian name, were always arm in arm when they walked, pinned up each other's train for the dance, and were not to be divided in the set; and if a rainy morning deprived them of other enjoyments, they were still resolute in meeting in defiance of wet and dirt, and shut themselves up, to read novels together.

Yes, novels; for I will not adopt that ungenerous and impolitic custom so common with novel-writers, of degrading by their contemptuous censure the very performances, to the number of which they are themselves adding -- joining with their greatest enemies in bestowing the harshest epithets on such works, and scarcely ever permitting them to be read by their own heroine, who, if she accidentally take up a novel, is sure to turn over its insipid pages with disgust. Alas! If the heroine of one novel be not patronized by the heroine of another, from whom can she expect protection and regard?

I cannot approve of it. Let us leave it to the reviewers to abuse such effusions of fancy at their leisure, and over every new novel to talk in threadbare strains of the trash with which the press now groans. Let us not desert one another; we are an injured body. Although our productions have afforded more extensive and unaffected pleasure than those of any other literary corporation in the world, no species of composition has been so much decried. From pride, ignorance, or fashion, our foes are almost as many as our readers.

And while the abilities of the nine-hundredth abridger of the History of England, or of the man who collects and publishes in a volume some dozen lines of Milton, Pope, and Prior, with a paper from the Spectator, and a chapter from Sterne, are eulogized by a thousand pens -- there seems almost a general wish of decrying the capacity and undervaluing the labour of the novelist, and of slighting the performances which have only genius, wit, and taste to recommend them.

"I am no novel-reader -- I seldom look into novels -- Do not imagine that I often read novels -- It is really very well for a novel." Such is the common cant.

"And what are you reading, Miss -- ?"

"Oh! It is only a novel!" replies the young lady, while she lays down her book with affected indifference, or momentary shame.

"It is only Cecilia, or Camilla, or Belinda"; or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language.

Now, had the same young lady been engaged with a volume of the Spectator, instead of such a work, how proudly would she have produced the book, and told its name; though the chances must be against her being occupied by any part of that voluminous publication, of which either the matter or manner would not disgust a young person of taste: the substance of its papers so often consisting in the statement of improbable circumstances, unnatural characters, and topics of conversation which no longer concern anyone living; and their language, too, frequently so coarse as to give no very favourable idea of the age that could endure it.

Regardless of one's feelings on the subject, it is impossible to deny the benefit the subscription library had on the selection of titles available to readers during the Regency. According to Yvonne Forsling, "Through the whole Eighteenth century about 150,000 titles were published in the English language. During the last two decades of that century book publishing increased around 400% and continued to grow in the Regency era." With the passing of the Public Libraries Act in 1850, most of the subscription libraries were replaced or taken over by town government and opened free of charge to the public.

Free to the public libraries were not a new thing, originating with the Greeks and Romans, and made famous in 1606 by Thomas Bodley's Bodleian Library, which was open to the "whole republic of the learned", but these repositories of learning and higher education were few and far between and likely to house more academic than entertaining literature. Without the Subscription library and the public they catered to, it is likely that many of the most beloved literature classics, including all of Austen's novels, would never have been published. For that, we are ever grateful.

***

Bibliography:

Edward Jacobs, Anonymous Signatures: Circulation Libraries, Conventionality and the Production of Gothic Romances, ELH, Vol. 62, No. 3 (1995), pp. 603-629.

Dierdre Lynch, Janeites: Austen's Disciples and Devotees, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

Yvonne Forsling, Regency Shopping: Booksellers and Publishers, Regency England

Enjoyed this article? If you don't want to miss a beat when it comes to Jane Austen, make sure you are signed up to the Jane Austen Newsletter for exclusive updates and discounts from our Online Gift Shop.

1 comment

Fascinating insight into how subscription libraries revolutionized access to literature in the Regency era, making novels more accessible to the middle class and fueling the rise of popular fiction. A pivotal moment in literary history! https://saveplus.ae/

SavePlus UAE

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.