Jane Austen’s Fame and Fortune, Now and Then

By Caroline Kerr Taylor

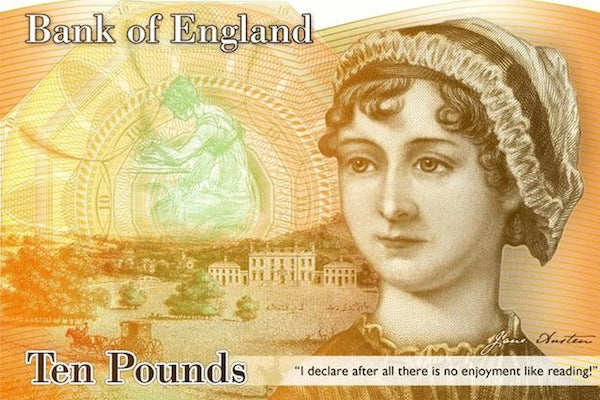

It is a truth universally acknowledged that Jane Austen continues to grow in popularity as an author even as her novels turn 200 years old. After Shakespeare, many would pronounce Austen the most popular and widely acclaimed literary figure in history. Her six novels are some of the most widely read literature in the world often outselling the books of top contemporary authors. According to Nielsen BookScan research, for example, in 2002 U.S. book stores sold 110,000 copies of Pride and Prejudice while John Grisham’s, The Runaway Jury, (a #1 best seller in 1996) sold 73,337 copies. Further, in recent years there have been numerous new editions of her books, various translations, dozens of TV adaptations and feature films, in addition to prequels, sequels and spin-offs, as well as, new biographies and articles on Austen herself.

By Caroline Kerr Taylor

It is a truth universally acknowledged that Jane Austen continues to grow in popularity as an author even as her novels turn 200 years old. After Shakespeare, many would pronounce Austen the most popular and widely acclaimed literary figure in history. Her six novels are some of the most widely read literature in the world often outselling the books of top contemporary authors. According to Nielsen BookScan research, for example, in 2002 U.S. book stores sold 110,000 copies of Pride and Prejudice while John Grisham’s, The Runaway Jury, (a #1 best seller in 1996) sold 73,337 copies. Further, in recent years there have been numerous new editions of her books, various translations, dozens of TV adaptations and feature films, in addition to prequels, sequels and spin-offs, as well as, new biographies and articles on Austen herself.

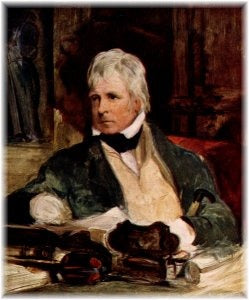

Austen is unquestionably a literary star today, but how was she received in her own day? Did she enjoy similar adulation? Other 19th century literary stars such as Dickens or Scott did enjoy a great deal of celebrity in their lifetimes. Austen’s reception was more low key. It is important to note that her name was not attached to any of her novels. Sense and Sensibility, her first published novel, was signed “By A Lady”. All her other books were attributed “to the author” of her previously published books. This practice was not uncommon. Even Walter Scott, well known for his poetry, initially did not use his name when he branched out into historical novels.

Austen is unquestionably a literary star today, but how was she received in her own day? Did she enjoy similar adulation? Other 19th century literary stars such as Dickens or Scott did enjoy a great deal of celebrity in their lifetimes. Austen’s reception was more low key. It is important to note that her name was not attached to any of her novels. Sense and Sensibility, her first published novel, was signed “By A Lady”. All her other books were attributed “to the author” of her previously published books. This practice was not uncommon. Even Walter Scott, well known for his poetry, initially did not use his name when he branched out into historical novels.

Jane’s notoriety was gained essentially by word of mouth. While she did not promote herself, her brother, Henry, did. Henry, along with her sister, Cassandra, were her biggest supporters. Cassandra was the first person privy to each novel as it was developed. Henry played several roles. At the time of the publishing of her novels he was a successful London banker. Because her first novel Sense and Sensibility was published on commission Austen needed to come up with the money to have it published. Having no money of her own she depended on Henry’s financial support to bring her books into the reading world. He not only provided financial support where needed but also acted as a liaison with her publishers. In the early 1800’s it was very much a man’s world. Henry assisted his sister by helping her navigate the professional world. He also mixed with influential people who could afford to buy books for pleasure and would share their reading experiences with others. In letters to her family Austen asked them not to share the fact that she was the author of her books, but her brother Henry couldn’t help himself. Bursting with pride Henry often let it slip that his sister Jane was, indeed, the author. Before long the word was circulating at dinner parties, afternoon teas, in letters, etc.

Jane’s notoriety was gained essentially by word of mouth. While she did not promote herself, her brother, Henry, did. Henry, along with her sister, Cassandra, were her biggest supporters. Cassandra was the first person privy to each novel as it was developed. Henry played several roles. At the time of the publishing of her novels he was a successful London banker. Because her first novel Sense and Sensibility was published on commission Austen needed to come up with the money to have it published. Having no money of her own she depended on Henry’s financial support to bring her books into the reading world. He not only provided financial support where needed but also acted as a liaison with her publishers. In the early 1800’s it was very much a man’s world. Henry assisted his sister by helping her navigate the professional world. He also mixed with influential people who could afford to buy books for pleasure and would share their reading experiences with others. In letters to her family Austen asked them not to share the fact that she was the author of her books, but her brother Henry couldn’t help himself. Bursting with pride Henry often let it slip that his sister Jane was, indeed, the author. Before long the word was circulating at dinner parties, afternoon teas, in letters, etc.

In 2016 Austen’s fourth novel, Emma (released in December 1815 but dated 1816), turns 200 years old. The first editions of her books: Sense & Sensibility, Pride & Prejudice and Mansfield Park had sold out. Looking back over Austen’s life she had a lot to celebrate with the publication of this fourth novel. Thomas Egerton, who printed her first three books, was a publisher of military themes primarily. He was not known for novels. After a disagreement over a second edition of Mansfield Park, Austen sought out a new publisher. With the help of Henry she was taken on by prominent London publisher John Murray. It was a significant step forward. Murray’s publishing house included the very popular Lord Byron as well as the famous Walter Scott as clients.

In 2016 Austen’s fourth novel, Emma (released in December 1815 but dated 1816), turns 200 years old. The first editions of her books: Sense & Sensibility, Pride & Prejudice and Mansfield Park had sold out. Looking back over Austen’s life she had a lot to celebrate with the publication of this fourth novel. Thomas Egerton, who printed her first three books, was a publisher of military themes primarily. He was not known for novels. After a disagreement over a second edition of Mansfield Park, Austen sought out a new publisher. With the help of Henry she was taken on by prominent London publisher John Murray. It was a significant step forward. Murray’s publishing house included the very popular Lord Byron as well as the famous Walter Scott as clients.

Frances Talbot, by Thomas Phillips, 1802. Frances would later become Countess Morley, receiving a personal copy of Emma, from Jane Austen, as well as mistaken credit for penning Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice.

It is interesting that Austen’s novels about everyday country life found her largest admirers from what Claire Tomalin calls the “beau monde” influential people whose tastes and judgments were important. The playwright Richard Sheridan was a fan. The sister of the Duchess of Devonshire enjoyed her novels. Charlotte, the daughter of the Prince Regent, identified with Marianne in Sense & Sensibility. The Countess of Morley in her letter to Austen in December of 1815 writes, “I am already become intimate in the Woodhouse family & feel that they will not amuse or interest me less than the Bennetts, Bertrams, Norriss & all their admirable predecessors. I can give them no higher praise.” Austen’s brother, Charles, wrote from Sicily in May of 1815: “Books became the subject of conversation, and I praised “Waverly” highly, when a young man present observed that nothing had come out for years to be compared with Pride & Prejudice, Sense & Sensibility…” The speaker of this praise was the eldest son of Lord Holland.

Jane’s esteem was also growing beyond the boundaries of England. She learned through her brother Henry that Lady Robert Kerr from Scotland had sung her praises and a Mrs. Fletcher, a wife of a judge in Ireland, was eager to learn about her. These accolades would have been thrilling.

Frances Talbot, by Thomas Phillips, 1802. Frances would later become Countess Morley, receiving a personal copy of Emma, from Jane Austen, as well as mistaken credit for penning Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice.

It is interesting that Austen’s novels about everyday country life found her largest admirers from what Claire Tomalin calls the “beau monde” influential people whose tastes and judgments were important. The playwright Richard Sheridan was a fan. The sister of the Duchess of Devonshire enjoyed her novels. Charlotte, the daughter of the Prince Regent, identified with Marianne in Sense & Sensibility. The Countess of Morley in her letter to Austen in December of 1815 writes, “I am already become intimate in the Woodhouse family & feel that they will not amuse or interest me less than the Bennetts, Bertrams, Norriss & all their admirable predecessors. I can give them no higher praise.” Austen’s brother, Charles, wrote from Sicily in May of 1815: “Books became the subject of conversation, and I praised “Waverly” highly, when a young man present observed that nothing had come out for years to be compared with Pride & Prejudice, Sense & Sensibility…” The speaker of this praise was the eldest son of Lord Holland.

Jane’s esteem was also growing beyond the boundaries of England. She learned through her brother Henry that Lady Robert Kerr from Scotland had sung her praises and a Mrs. Fletcher, a wife of a judge in Ireland, was eager to learn about her. These accolades would have been thrilling.

The inscription dedicating the novel Emma

The ultimate endorsement took place in l815. First, Austen learned that the Prince Regent (heir to the throne) had read and admired her novels. His librarian, Mr. Clarke, was instructed to invite her to visit the Prince Regent’s Carleton House library. While perusing the library together Mr. Clarke invited Austen to dedicate any future work to the Prince Regent. Truth be told, Jane was not a particular fan of the Prince Regent. She abhorred his decadent lifestyle and the ill-treatment of his wife. However, realizing that this was more than a suggestion but rather a command Jane alerted Murray that Emma would be dedicated by permission to the Prince Regent. Murray was delighted and helped her with the appropriate dedication as well as printing 2,000 copies of Emma which was her largest edition yet.

Second, Sir Walter Scott, the most popular writer of the day, wrote a positive review of Emma in the Quarterly Review. It must have been quite heady for Austen, someone who read and admired Scott’s writing, to be reviewed by the great man himself. Over the years Scott’s regard for Austen continued to grow. Years later he paid her the highest compliment, “That young lady has a talent for describing the involvements and feelings and characters of ordinary life which is to me the most wonderful I have ever met with”. It is interesting to note that in Persuasion the heroine, Anne Elliot, speaks of her admiration for both Byron and Scott.

The inscription dedicating the novel Emma

The ultimate endorsement took place in l815. First, Austen learned that the Prince Regent (heir to the throne) had read and admired her novels. His librarian, Mr. Clarke, was instructed to invite her to visit the Prince Regent’s Carleton House library. While perusing the library together Mr. Clarke invited Austen to dedicate any future work to the Prince Regent. Truth be told, Jane was not a particular fan of the Prince Regent. She abhorred his decadent lifestyle and the ill-treatment of his wife. However, realizing that this was more than a suggestion but rather a command Jane alerted Murray that Emma would be dedicated by permission to the Prince Regent. Murray was delighted and helped her with the appropriate dedication as well as printing 2,000 copies of Emma which was her largest edition yet.

Second, Sir Walter Scott, the most popular writer of the day, wrote a positive review of Emma in the Quarterly Review. It must have been quite heady for Austen, someone who read and admired Scott’s writing, to be reviewed by the great man himself. Over the years Scott’s regard for Austen continued to grow. Years later he paid her the highest compliment, “That young lady has a talent for describing the involvements and feelings and characters of ordinary life which is to me the most wonderful I have ever met with”. It is interesting to note that in Persuasion the heroine, Anne Elliot, speaks of her admiration for both Byron and Scott.

Besides having a prominent publisher and getting recognition from the “beau monde”, including the Prince Regent, Austen was now earning her own money. As a single woman living in 18th century England, she was entirely dependent on her family for her finances. Women of her class didn’t work outside the home. She had been given a 20£ yearly allowance while her father was living. Her father died in 1805 leaving his wife and daughters with an annual income of 160£. Jane’s brothers contributed as best they could but contributions were limited as they had families of their own. It wasn’t until Edward, one of Jane’s brothers, who had inherited large properties, offered them a cottage on his Chawton estate in l809 that their lives found a degree of stability and comfort. In letters to her oldest niece, Fanny, Austen writes about this difficulty: “Single women have a dreadful propensity for being poor….”, and “…tho’ I like praise as well as anybody, I like what Edward calls pewter, too”. Writing to her brother Frank Jane says, “I have written myself into 250£ which only makes me long for more”.

Besides having a prominent publisher and getting recognition from the “beau monde”, including the Prince Regent, Austen was now earning her own money. As a single woman living in 18th century England, she was entirely dependent on her family for her finances. Women of her class didn’t work outside the home. She had been given a 20£ yearly allowance while her father was living. Her father died in 1805 leaving his wife and daughters with an annual income of 160£. Jane’s brothers contributed as best they could but contributions were limited as they had families of their own. It wasn’t until Edward, one of Jane’s brothers, who had inherited large properties, offered them a cottage on his Chawton estate in l809 that their lives found a degree of stability and comfort. In letters to her oldest niece, Fanny, Austen writes about this difficulty: “Single women have a dreadful propensity for being poor….”, and “…tho’ I like praise as well as anybody, I like what Edward calls pewter, too”. Writing to her brother Frank Jane says, “I have written myself into 250£ which only makes me long for more”.

From the accounts rendered at the time of her death it appears that income from the publishing of her first four novels earned her more than 600£. This was not a lot of money but for an unmarried woman in her social standing it was significant. The author Paula Byrne equates the 300£ Austen made from the first edition of Mansfield Park to approximately 20,000£ or 30,000 U.S. dollars in today’s values (600£ would therefore be approximately 40,000£ or 60,000 U.S. dollars). Upon Jane’s death she left the majority of her money and her manuscripts to her sister Cassandra. Murray bought Northanger Abbey and Persuasion from Cassandra for 500£. Jane was already working on another book at the time of her death. Had she lived she would have continued to write and make a comfortable living. In 1832, fifteen years after his sister’s death, Henry negotiated with the publisher, Richard Bentley, for a new edition of Austen’s six novels. Bentley bought the five publishing rights owned by Cassandra for 210£. Bentley had to pay Egerton’s heirs for Pride and Prejudice to complete the collection.

Today Austen is a super star among literary figures. She could not have imagined such acclaim during her lifetime. As an ardent Jane Austen fan it is satisfying to know that during her short life (she died at the age of 41) and limited literary career (six and a half years) she did in fact enjoy a degree of fulfillment, affirmation, and financial success. The clergyman’s daughter from a small country village in Hampshire had done well…quite well indeed.

From the accounts rendered at the time of her death it appears that income from the publishing of her first four novels earned her more than 600£. This was not a lot of money but for an unmarried woman in her social standing it was significant. The author Paula Byrne equates the 300£ Austen made from the first edition of Mansfield Park to approximately 20,000£ or 30,000 U.S. dollars in today’s values (600£ would therefore be approximately 40,000£ or 60,000 U.S. dollars). Upon Jane’s death she left the majority of her money and her manuscripts to her sister Cassandra. Murray bought Northanger Abbey and Persuasion from Cassandra for 500£. Jane was already working on another book at the time of her death. Had she lived she would have continued to write and make a comfortable living. In 1832, fifteen years after his sister’s death, Henry negotiated with the publisher, Richard Bentley, for a new edition of Austen’s six novels. Bentley bought the five publishing rights owned by Cassandra for 210£. Bentley had to pay Egerton’s heirs for Pride and Prejudice to complete the collection.

Today Austen is a super star among literary figures. She could not have imagined such acclaim during her lifetime. As an ardent Jane Austen fan it is satisfying to know that during her short life (she died at the age of 41) and limited literary career (six and a half years) she did in fact enjoy a degree of fulfillment, affirmation, and financial success. The clergyman’s daughter from a small country village in Hampshire had done well…quite well indeed.

Caroline Kerr Taylor authored many educational work books as an editor at Creative Teaching Press, Cypress, California. After some years living abroad, in New Zealand, she now lives in Newport Beach, California, and enjoys freelance writing. Her most recent article, "A Visit to Harper Lee's Monroeville" was published in online magazine, Literary Traveler, October 8, 2012. In New Zealand she had a feature story in NZ House & Garden, May 2009.