October in Regency Bath

With the skies full of migrating birds and the leaves turning to amber and brown, it's the season to be thinking about time and change. In the autumn of 1801, the Austens had moved into Sydney Place. Now, in October 1804, the three-year lease was about to expire. After several extravagant summers spent by the sea, the family could not really afford to renew it. They had fallen back on 24, Green Park Buildings as their next choice, and this was not at all to Jane's liking. She had already rejected it in her Great House Hunt of spring 1801, because of - well, was it the damp in the cellar, or an instinctive foreboding, something surprisingly akin to the "vapours"? Yet it was cheaper, and outwardly pleasant and elegant. Perhaps these irrational fears would be eased by a gentle stroll over to see it once again before the move, accompanied by her respected father. And that is her programme for this mellow, overcast afternoon.

As usual, Jane keeps her own counsel about her worries as she walks beside Mr Austen, adjusting her quick step to his leisurely pace. Pulteney Street may boast the broadest and best-kept pavements in Bath, but she still tucks her free hand under his arm to prevent him from stumbling. In the eyes of the world, of course, this is the gesture of a dutiful daughter requiring her father's escort and protection.

They talk companionably. Perhaps their subject is the packet of books she has under her other arm - volumes they intend to return to the circulating library at no, 5, Abbey Churchyard. By sharing the annual subscription fee of half a guinea, they have been able to compensate for the sad loss of the library at Steventon at the time of the removal to Bath. This week, Jane has been re-reading Gisborne's Inquiry into the Duties of the Female Sex. She tells her father that, to her surprise, she rather likes it. Certainly it's a great deal more palatable to females than Fordyce's sermons. Fordyce, in her view, is only useful for one purpose - to make curl papers out of the torn-up pages, as Lydia Languish does in The Rivals. Lydia - always a deliciously wayward, spoilt sort of name. Maybe Lydia Bennet of that unpublished novel of hers, First Impressions, could be shown reacting to someone - say the pompous Mr Collins - reading Fordyce's sermons out loud to her. Jane declares that she feels it's time to go back and revise this, his favourite of her stories, even if the publisher Cadell didn't think it worth taking on.

As usual, Jane keeps her own counsel about her worries as she walks beside Mr Austen, adjusting her quick step to his leisurely pace. Pulteney Street may boast the broadest and best-kept pavements in Bath, but she still tucks her free hand under his arm to prevent him from stumbling. In the eyes of the world, of course, this is the gesture of a dutiful daughter requiring her father's escort and protection.

They talk companionably. Perhaps their subject is the packet of books she has under her other arm - volumes they intend to return to the circulating library at no, 5, Abbey Churchyard. By sharing the annual subscription fee of half a guinea, they have been able to compensate for the sad loss of the library at Steventon at the time of the removal to Bath. This week, Jane has been re-reading Gisborne's Inquiry into the Duties of the Female Sex. She tells her father that, to her surprise, she rather likes it. Certainly it's a great deal more palatable to females than Fordyce's sermons. Fordyce, in her view, is only useful for one purpose - to make curl papers out of the torn-up pages, as Lydia Languish does in The Rivals. Lydia - always a deliciously wayward, spoilt sort of name. Maybe Lydia Bennet of that unpublished novel of hers, First Impressions, could be shown reacting to someone - say the pompous Mr Collins - reading Fordyce's sermons out loud to her. Jane declares that she feels it's time to go back and revise this, his favourite of her stories, even if the publisher Cadell didn't think it worth taking on.

Mr Austen pats her arm and reminds her that things look hopeful for Susan. Her tale of a young girl's first visit to Bath has been accepted by Crosby for imminent publication, and will soon be out on the bookstalls. Jane allows herself a happy sigh at the memory of that spending spree she had in Milsom Street with Crosby's ten pounds advance payment, but merely replies to her father that Crosby himself appears to be in no particular hurry.

All in God's good time, her father's characteristic serene smile seems to say. He's relieved to hear his daughter talk with something of her old enjoyment about her writing again. The new work, The Watsons, had caused her much trouble over the last year. She had not let him see any of the blotted and scored drafts, but from what he could gather, they sounded a sour bunch of old maids in the making. He gives a gentle sigh. If only the family had managed to find her a husband - he dreads to think of her future, once he's gone to a better world, without even his clergy pension to live on. Yet where would they have found a Benedick to match this witty, complicated Beatrice of theirs?

Mr Austen pats her arm and reminds her that things look hopeful for Susan. Her tale of a young girl's first visit to Bath has been accepted by Crosby for imminent publication, and will soon be out on the bookstalls. Jane allows herself a happy sigh at the memory of that spending spree she had in Milsom Street with Crosby's ten pounds advance payment, but merely replies to her father that Crosby himself appears to be in no particular hurry.

All in God's good time, her father's characteristic serene smile seems to say. He's relieved to hear his daughter talk with something of her old enjoyment about her writing again. The new work, The Watsons, had caused her much trouble over the last year. She had not let him see any of the blotted and scored drafts, but from what he could gather, they sounded a sour bunch of old maids in the making. He gives a gentle sigh. If only the family had managed to find her a husband - he dreads to think of her future, once he's gone to a better world, without even his clergy pension to live on. Yet where would they have found a Benedick to match this witty, complicated Beatrice of theirs?

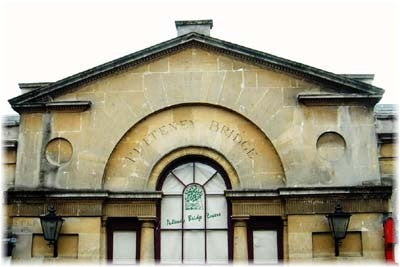

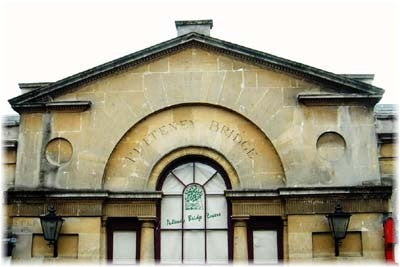

At length, they reach the end of the boulevard's fine perspective. They pass the fountain in Laura Place, saunter along Argyle Street and onto Pulteney Bridge itself. While Jane, who loves to window-shop, pauses to admire a display of lace, Mr Austen takes a little harmless pleasure in his own reflection in the glass. He hopes he will be forgiven for wanting the passers-by to know that his snowy locks are all his own hair. He surveys his scholarly features - his beaky nose, his benevolent smile. Yes. In his youth they had called him "the handsome proctor" and he feels with some complacency that even now he is not a bad-looking man for seventy-three. He taps out a gentle rhythmn with his cane on the pavement, waiting for her daughter to finish her scrutiny of the shawls and caps - only to realise her bright, shrewd eyes in the reflection are meeting his.

"Beware of vanity, Papa, otherwise I shall put you in a book. I'm thinking of an absurd elderly gentleman living in cold elegance up on, say, Camden Place, who has nothing but looking glasses on the walls of his house -"

"I was - ah - merely reflecting, my dear, as you might say, meditating on the immortal words of George Herbert:

At length, they reach the end of the boulevard's fine perspective. They pass the fountain in Laura Place, saunter along Argyle Street and onto Pulteney Bridge itself. While Jane, who loves to window-shop, pauses to admire a display of lace, Mr Austen takes a little harmless pleasure in his own reflection in the glass. He hopes he will be forgiven for wanting the passers-by to know that his snowy locks are all his own hair. He surveys his scholarly features - his beaky nose, his benevolent smile. Yes. In his youth they had called him "the handsome proctor" and he feels with some complacency that even now he is not a bad-looking man for seventy-three. He taps out a gentle rhythmn with his cane on the pavement, waiting for her daughter to finish her scrutiny of the shawls and caps - only to realise her bright, shrewd eyes in the reflection are meeting his.

"Beware of vanity, Papa, otherwise I shall put you in a book. I'm thinking of an absurd elderly gentleman living in cold elegance up on, say, Camden Place, who has nothing but looking glasses on the walls of his house -"

"I was - ah - merely reflecting, my dear, as you might say, meditating on the immortal words of George Herbert:

What a pleasing view through to the river through the window. I'm told the shops of Pulteney Bridge are modelled on a famous bridge in Venice."

But Jane is not fooled, and neither is he - the essence of their relationship is this element of affectionate banter. They laugh together and look through at the sluggishly flowing Avon below them. It gives them both a frisson to stop on the bridge, caught in this way between the past and the future.

They walk on through the city centre, along the narrowest thoroughfares of medieval Bath, across the Abbey Churchyard, and up a flight of stairs into Mr Meyler's splendidly-stocked library at No 5. They enjoy the first fire of the season and scan the London papers for details of the whereabouts of Frank and Charles, the sailor brothers. Then it's to the market by the Guildhall to buy some ripe pears to remind them of Hampshire, and to glance up at the rooftop figure of justice with her uplifted scales. Her sword holds no terrors for a just man who has been in constant preparation for the next world.

What a pleasing view through to the river through the window. I'm told the shops of Pulteney Bridge are modelled on a famous bridge in Venice."

But Jane is not fooled, and neither is he - the essence of their relationship is this element of affectionate banter. They laugh together and look through at the sluggishly flowing Avon below them. It gives them both a frisson to stop on the bridge, caught in this way between the past and the future.

They walk on through the city centre, along the narrowest thoroughfares of medieval Bath, across the Abbey Churchyard, and up a flight of stairs into Mr Meyler's splendidly-stocked library at No 5. They enjoy the first fire of the season and scan the London papers for details of the whereabouts of Frank and Charles, the sailor brothers. Then it's to the market by the Guildhall to buy some ripe pears to remind them of Hampshire, and to glance up at the rooftop figure of justice with her uplifted scales. Her sword holds no terrors for a just man who has been in constant preparation for the next world.

At last, father and daughter, so soon to be parted by death, reach 27, Green Park Buildings. The daughter, as is her custom, tries to make the best of the place. She points out, as the landlord's young man had done back in 1801, the elegant fan tracery over the door, the pleasant open situation onto King's Mead and the Avon. It would be nearer to the Baths and the Pump Room and the doctors and to all the paraphenalia - should it be needed - of failing health. There would be advantages to both aged parents in living here.

But the summer was over - what would it look like at the end of November, with the river in tawny flood, or on a dripping wet day in melancholy January? A green Yuletide maketh a fat kirkyard, as the old saying goes. What was it about Green Park Buildings that Jane distrusted?

It was damp, yes, that was it, and surely that was only it. Jane smiled ironically at herself. Surely she needed no ghost to tell her that a house near the river would be damp.

Sue Le Blond lives in Bradford-on-Avon and works part-time at the Jane Austen Centre as a guide. She is a freelance writer, creative writing teacher and theatre reviewer. The collected website articles, Jane in Bath will be published next year. Sue welcomes feedback and can be contacted by email via sue@le-blond.f

Enjoyed this article? Visit our giftshop and escape into the world of Jane Austen.

At last, father and daughter, so soon to be parted by death, reach 27, Green Park Buildings. The daughter, as is her custom, tries to make the best of the place. She points out, as the landlord's young man had done back in 1801, the elegant fan tracery over the door, the pleasant open situation onto King's Mead and the Avon. It would be nearer to the Baths and the Pump Room and the doctors and to all the paraphenalia - should it be needed - of failing health. There would be advantages to both aged parents in living here.

But the summer was over - what would it look like at the end of November, with the river in tawny flood, or on a dripping wet day in melancholy January? A green Yuletide maketh a fat kirkyard, as the old saying goes. What was it about Green Park Buildings that Jane distrusted?

It was damp, yes, that was it, and surely that was only it. Jane smiled ironically at herself. Surely she needed no ghost to tell her that a house near the river would be damp.

Sue Le Blond lives in Bradford-on-Avon and works part-time at the Jane Austen Centre as a guide. She is a freelance writer, creative writing teacher and theatre reviewer. The collected website articles, Jane in Bath will be published next year. Sue welcomes feedback and can be contacted by email via sue@le-blond.f

Enjoyed this article? Visit our giftshop and escape into the world of Jane Austen.

As usual, Jane keeps her own counsel about her worries as she walks beside Mr Austen, adjusting her quick step to his leisurely pace. Pulteney Street may boast the broadest and best-kept pavements in Bath, but she still tucks her free hand under his arm to prevent him from stumbling. In the eyes of the world, of course, this is the gesture of a dutiful daughter requiring her father's escort and protection.

They talk companionably. Perhaps their subject is the packet of books she has under her other arm - volumes they intend to return to the circulating library at no, 5, Abbey Churchyard. By sharing the annual subscription fee of half a guinea, they have been able to compensate for the sad loss of the library at Steventon at the time of the removal to Bath. This week, Jane has been re-reading Gisborne's Inquiry into the Duties of the Female Sex. She tells her father that, to her surprise, she rather likes it. Certainly it's a great deal more palatable to females than Fordyce's sermons. Fordyce, in her view, is only useful for one purpose - to make curl papers out of the torn-up pages, as Lydia Languish does in The Rivals. Lydia - always a deliciously wayward, spoilt sort of name. Maybe Lydia Bennet of that unpublished novel of hers, First Impressions, could be shown reacting to someone - say the pompous Mr Collins - reading Fordyce's sermons out loud to her. Jane declares that she feels it's time to go back and revise this, his favourite of her stories, even if the publisher Cadell didn't think it worth taking on.

As usual, Jane keeps her own counsel about her worries as she walks beside Mr Austen, adjusting her quick step to his leisurely pace. Pulteney Street may boast the broadest and best-kept pavements in Bath, but she still tucks her free hand under his arm to prevent him from stumbling. In the eyes of the world, of course, this is the gesture of a dutiful daughter requiring her father's escort and protection.

They talk companionably. Perhaps their subject is the packet of books she has under her other arm - volumes they intend to return to the circulating library at no, 5, Abbey Churchyard. By sharing the annual subscription fee of half a guinea, they have been able to compensate for the sad loss of the library at Steventon at the time of the removal to Bath. This week, Jane has been re-reading Gisborne's Inquiry into the Duties of the Female Sex. She tells her father that, to her surprise, she rather likes it. Certainly it's a great deal more palatable to females than Fordyce's sermons. Fordyce, in her view, is only useful for one purpose - to make curl papers out of the torn-up pages, as Lydia Languish does in The Rivals. Lydia - always a deliciously wayward, spoilt sort of name. Maybe Lydia Bennet of that unpublished novel of hers, First Impressions, could be shown reacting to someone - say the pompous Mr Collins - reading Fordyce's sermons out loud to her. Jane declares that she feels it's time to go back and revise this, his favourite of her stories, even if the publisher Cadell didn't think it worth taking on.

Mr Austen pats her arm and reminds her that things look hopeful for Susan. Her tale of a young girl's first visit to Bath has been accepted by Crosby for imminent publication, and will soon be out on the bookstalls. Jane allows herself a happy sigh at the memory of that spending spree she had in Milsom Street with Crosby's ten pounds advance payment, but merely replies to her father that Crosby himself appears to be in no particular hurry.

All in God's good time, her father's characteristic serene smile seems to say. He's relieved to hear his daughter talk with something of her old enjoyment about her writing again. The new work, The Watsons, had caused her much trouble over the last year. She had not let him see any of the blotted and scored drafts, but from what he could gather, they sounded a sour bunch of old maids in the making. He gives a gentle sigh. If only the family had managed to find her a husband - he dreads to think of her future, once he's gone to a better world, without even his clergy pension to live on. Yet where would they have found a Benedick to match this witty, complicated Beatrice of theirs?

Mr Austen pats her arm and reminds her that things look hopeful for Susan. Her tale of a young girl's first visit to Bath has been accepted by Crosby for imminent publication, and will soon be out on the bookstalls. Jane allows herself a happy sigh at the memory of that spending spree she had in Milsom Street with Crosby's ten pounds advance payment, but merely replies to her father that Crosby himself appears to be in no particular hurry.

All in God's good time, her father's characteristic serene smile seems to say. He's relieved to hear his daughter talk with something of her old enjoyment about her writing again. The new work, The Watsons, had caused her much trouble over the last year. She had not let him see any of the blotted and scored drafts, but from what he could gather, they sounded a sour bunch of old maids in the making. He gives a gentle sigh. If only the family had managed to find her a husband - he dreads to think of her future, once he's gone to a better world, without even his clergy pension to live on. Yet where would they have found a Benedick to match this witty, complicated Beatrice of theirs?

At length, they reach the end of the boulevard's fine perspective. They pass the fountain in Laura Place, saunter along Argyle Street and onto Pulteney Bridge itself. While Jane, who loves to window-shop, pauses to admire a display of lace, Mr Austen takes a little harmless pleasure in his own reflection in the glass. He hopes he will be forgiven for wanting the passers-by to know that his snowy locks are all his own hair. He surveys his scholarly features - his beaky nose, his benevolent smile. Yes. In his youth they had called him "the handsome proctor" and he feels with some complacency that even now he is not a bad-looking man for seventy-three. He taps out a gentle rhythmn with his cane on the pavement, waiting for her daughter to finish her scrutiny of the shawls and caps - only to realise her bright, shrewd eyes in the reflection are meeting his.

"Beware of vanity, Papa, otherwise I shall put you in a book. I'm thinking of an absurd elderly gentleman living in cold elegance up on, say, Camden Place, who has nothing but looking glasses on the walls of his house -"

"I was - ah - merely reflecting, my dear, as you might say, meditating on the immortal words of George Herbert:

At length, they reach the end of the boulevard's fine perspective. They pass the fountain in Laura Place, saunter along Argyle Street and onto Pulteney Bridge itself. While Jane, who loves to window-shop, pauses to admire a display of lace, Mr Austen takes a little harmless pleasure in his own reflection in the glass. He hopes he will be forgiven for wanting the passers-by to know that his snowy locks are all his own hair. He surveys his scholarly features - his beaky nose, his benevolent smile. Yes. In his youth they had called him "the handsome proctor" and he feels with some complacency that even now he is not a bad-looking man for seventy-three. He taps out a gentle rhythmn with his cane on the pavement, waiting for her daughter to finish her scrutiny of the shawls and caps - only to realise her bright, shrewd eyes in the reflection are meeting his.

"Beware of vanity, Papa, otherwise I shall put you in a book. I'm thinking of an absurd elderly gentleman living in cold elegance up on, say, Camden Place, who has nothing but looking glasses on the walls of his house -"

"I was - ah - merely reflecting, my dear, as you might say, meditating on the immortal words of George Herbert:

'A man that looks on glass On it may stay his eye Or if he pleaseth through it pass And may the heavens espy.'

What a pleasing view through to the river through the window. I'm told the shops of Pulteney Bridge are modelled on a famous bridge in Venice."

But Jane is not fooled, and neither is he - the essence of their relationship is this element of affectionate banter. They laugh together and look through at the sluggishly flowing Avon below them. It gives them both a frisson to stop on the bridge, caught in this way between the past and the future.

They walk on through the city centre, along the narrowest thoroughfares of medieval Bath, across the Abbey Churchyard, and up a flight of stairs into Mr Meyler's splendidly-stocked library at No 5. They enjoy the first fire of the season and scan the London papers for details of the whereabouts of Frank and Charles, the sailor brothers. Then it's to the market by the Guildhall to buy some ripe pears to remind them of Hampshire, and to glance up at the rooftop figure of justice with her uplifted scales. Her sword holds no terrors for a just man who has been in constant preparation for the next world.

What a pleasing view through to the river through the window. I'm told the shops of Pulteney Bridge are modelled on a famous bridge in Venice."

But Jane is not fooled, and neither is he - the essence of their relationship is this element of affectionate banter. They laugh together and look through at the sluggishly flowing Avon below them. It gives them both a frisson to stop on the bridge, caught in this way between the past and the future.

They walk on through the city centre, along the narrowest thoroughfares of medieval Bath, across the Abbey Churchyard, and up a flight of stairs into Mr Meyler's splendidly-stocked library at No 5. They enjoy the first fire of the season and scan the London papers for details of the whereabouts of Frank and Charles, the sailor brothers. Then it's to the market by the Guildhall to buy some ripe pears to remind them of Hampshire, and to glance up at the rooftop figure of justice with her uplifted scales. Her sword holds no terrors for a just man who has been in constant preparation for the next world.

At last, father and daughter, so soon to be parted by death, reach 27, Green Park Buildings. The daughter, as is her custom, tries to make the best of the place. She points out, as the landlord's young man had done back in 1801, the elegant fan tracery over the door, the pleasant open situation onto King's Mead and the Avon. It would be nearer to the Baths and the Pump Room and the doctors and to all the paraphenalia - should it be needed - of failing health. There would be advantages to both aged parents in living here.

But the summer was over - what would it look like at the end of November, with the river in tawny flood, or on a dripping wet day in melancholy January? A green Yuletide maketh a fat kirkyard, as the old saying goes. What was it about Green Park Buildings that Jane distrusted?

It was damp, yes, that was it, and surely that was only it. Jane smiled ironically at herself. Surely she needed no ghost to tell her that a house near the river would be damp.

Sue Le Blond lives in Bradford-on-Avon and works part-time at the Jane Austen Centre as a guide. She is a freelance writer, creative writing teacher and theatre reviewer. The collected website articles, Jane in Bath will be published next year. Sue welcomes feedback and can be contacted by email via sue@le-blond.f

Enjoyed this article? Visit our giftshop and escape into the world of Jane Austen.

At last, father and daughter, so soon to be parted by death, reach 27, Green Park Buildings. The daughter, as is her custom, tries to make the best of the place. She points out, as the landlord's young man had done back in 1801, the elegant fan tracery over the door, the pleasant open situation onto King's Mead and the Avon. It would be nearer to the Baths and the Pump Room and the doctors and to all the paraphenalia - should it be needed - of failing health. There would be advantages to both aged parents in living here.

But the summer was over - what would it look like at the end of November, with the river in tawny flood, or on a dripping wet day in melancholy January? A green Yuletide maketh a fat kirkyard, as the old saying goes. What was it about Green Park Buildings that Jane distrusted?

It was damp, yes, that was it, and surely that was only it. Jane smiled ironically at herself. Surely she needed no ghost to tell her that a house near the river would be damp.

Sue Le Blond lives in Bradford-on-Avon and works part-time at the Jane Austen Centre as a guide. She is a freelance writer, creative writing teacher and theatre reviewer. The collected website articles, Jane in Bath will be published next year. Sue welcomes feedback and can be contacted by email via sue@le-blond.f

Enjoyed this article? Visit our giftshop and escape into the world of Jane Austen.