From Classic to Romantic: Changes in the Regency Silhouette

The Regency silhouette went through a fair few changes...

Wednesday. -- Mrs. Mussell has got my gown, and I will endeavour to explain what her intentions are. It is to be a round gown, with a jacket and a frock front, like Cath. Bigg's, to open at the side. The jacket is all in one with the body, and comes as far as the pocket-holes -- about half a quarter of a yard deep, I suppose, all the way round, cut off straight at the corners with a broad hem. No fulness appears either in the body or the flap; the back is quite plain in this form, and the sides equally so. The front is sloped round to the bosom and drawn in, and there is to be a frill of the same to put on occasionally when all one's handkerchiefs are dirty -- which frill must fall back. She is to put two breadths and a-half in the tail, and no gores -- gores not being so much worn as they were. There is nothing new in the sleeves: they are to be plain, with a fulness of the same falling down and gathered up underneath, just like some of Martha's, or perhaps a little longer. Low in the back behind, and a belt of the same. I can think of nothing more, though I am afraid of not being particular enough.

Jane Austen to Cassandra May 5, 1801

The popularity of the high-waisted regency gown is due to both to French influence in fashion and the Neoclassical rage that swept Europe during the 18th Century. Marie Antoinette is said to have inspired the round gown of the 1790′s, which is essentially a dress and robe joined together and tied in the front. Later, Josephine Bonaparte who reigned supreme in her position as a fashion icon, influenced the slim, high-waisted, gossamer thin chemise dress of the early 19th Century.

The round gown, a precursor of the Empire gown, had a soft, round silhouette, with full gatherings and a train, and straight, elbow-length sleeves. These gowns were in stark contrast to the stiff, brocaded or rigid silk dresses of the rococo period. The round gown’s train, which was common for a short time for day wear and lasted until 1805-06 for the evening, would be pinned up for the dance, as Katherine and Isabella did for each other in Northanger Abbey. One must question how practical these long white muslin dresses with their trailing trains were in England, a country renowned for wet weather and muddy roads.

In England especially, daytime dresses were more modest than their evening counterparts. A few French images depict young ladies wearing day gowns with plunging decolletes, but this was not generally the case, and it is a point that cinema costume makers frequently miss. Until 1810, a fichu or chemisette would fill in the neckline. At first, embroideries on hems and borders were influenced by classical Greek patterns. After Napoleon’s return from Egypt in 1804, decorative patterns began to reflect an eastern influence as well. Around 1808, the soft gathered gowns gave way to a slimmer and sleeker Regency silhouette.

Darted bodices began to appear and hemlines started to rise. Long sleeves and high necklines were worn during the day, while short sleeves and bare necklines were reserved for evening gowns. The sleeves were puffy and gathered, but the overall silhouette remained sleek, with the shoulders narrow. The shape of the corset changed to reflect the looser, draped, shorter waisted style.

Due to the war between England and France, and the restrictions of travel to the Continent, the designs of English gowns began to take on a character of their own, as French influence waned. Between 1808 and 1814, English waistlines lengthened and decorations were influenced by the Romantic movement and British culture. Dresses began to exhibit decorations that echoed the Gothic, Renaissance, Tudor, and Elizabethan periods. Ruffled edges, Van Dyke lace points, rows of tucks on hems and bodices, and slash puffed sleeves made their appearance. The length of the gown was raised off the ground, so that dainty kid slippers became quite visible.

After the 1814 peace treaty, English visitors to France began to realize just exactly how much British fashion had split from its French counterpart. Parisian waists had remained higher, and skirt hems were wider and trimmed with padded decorations, resulting in a cone-shaped look. English fashion quickly realigned itself with the French, and the silhouette changed yet again. Dresses now boasted long sleeves, high necks, and a very high waist, The simple classical silhouette was replaced by a fussier look. Ruffles appeared everywhere, on hems, sleeves, bodices, and even bonnets. In 1816-1817, the waistline fell just under a woman’s breasts, and could go no higher. There was only one way that waistlines could go, and by 1818, they began to drop by about an inch a year.

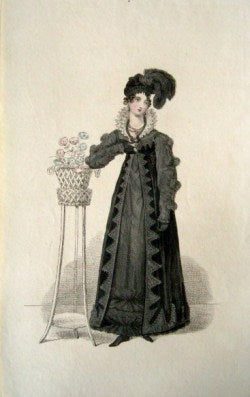

By 1820 the simple classic lines of the chemise dress had disappeared and completely given way to a stiffer, wider silhouette with a quite short hem. New corsets were designed to accommodate the longer waistline. Remarkably, Anglomania hit France, and the French began to copy the English fashion. The rows of ruffles, pleats, appliques, and horsehair-padded decorations stiffened the skirt into a conical shape, creating a puffy silhouette. Big hats were worn to counterbalance the broad shoulders, much as big hair balanced wide shoulder pads during the 1980′s. By 1825 the waist had reached a woman’s natural waistline in fashion plates, but according to evidence in museums, it would take another five years before this fashion caught up with the general public.

By 1820 the simple classic lines of the chemise dress had disappeared and completely given way to a stiffer, wider silhouette with a quite short hem. New corsets were designed to accommodate the longer waistline. Remarkably, Anglomania hit France, and the French began to copy the English fashion. The rows of ruffles, pleats, appliques, and horsehair-padded decorations stiffened the skirt into a conical shape, creating a puffy silhouette. Big hats were worn to counterbalance the broad shoulders, much as big hair balanced wide shoulder pads during the 1980′s. By 1825 the waist had reached a woman’s natural waistline in fashion plates, but according to evidence in museums, it would take another five years before this fashion caught up with the general public.  Leg of lamb sleeves (gigot sleeves) appeared, and dress decorations became intricate and theatrical. By 1820 the basic lines were almost submerged in ornamentation. The romantic past held a treasure trove of ideas for adorning a lady’s costume. From the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries came puffs bursting through slashed and the revival of the Spanish ruff. collars and cuffs developed points a la Van Dyke and sleeves could be a la Babrielle (after Garielle d’Estrees, mistress of Henry IV of France). Skirts were festooned with roses or made more flaring with crokscrew rolls … Fantasy seemed to now no bounds. (Ackermann’s Costume Plates, Stella Blum, page vi)

Leg of lamb sleeves (gigot sleeves) appeared, and dress decorations became intricate and theatrical. By 1820 the basic lines were almost submerged in ornamentation. The romantic past held a treasure trove of ideas for adorning a lady’s costume. From the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries came puffs bursting through slashed and the revival of the Spanish ruff. collars and cuffs developed points a la Van Dyke and sleeves could be a la Babrielle (after Garielle d’Estrees, mistress of Henry IV of France). Skirts were festooned with roses or made more flaring with crokscrew rolls … Fantasy seemed to now no bounds. (Ackermann’s Costume Plates, Stella Blum, page vi)

Read more about regency fashion trends in the links below:

Kathy Decker’s Regency Style, year by year

Jessamyn’s Regency Costume Companion

The Regency Fashion Page 1800s-1820s: Thumbnails

Fashion Prints: Walking Dresses, 1806-1810

Vic Sanborn oversees two blogs: Jane Austen’s World and Jane Austen Today. Before 2006 she merely adored Jane Austen and read Pride and Prejudice faithfully every year. These days, she is immersed in reading and writing about the author’s life and the Regency era. Co-founder of her local (and very small) book group, Janeites on the James, she began her blogs as a way to share her research on the Regency era for her novel, which sits unpublished on a dusty shelf. In her working life, Vic provides resources and professional development for teachers and administrators of Virginia’s adult education and literacy programs. This article was written for Jane Austen’s World and is used here with permission.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.