Younger Sons in Jane Austen’s England

This guest article is written by Rory Muir - a visiting research fellow at the University of Adelaide and a renowned expert on British history. You can buy a signed copy of his book, Gentleman of Uncertain Fortune.

Younger Sons in Jane Austen’s England

Like many people, I first read Jane Austen’s novels in my mid-teens when I was still at school, and I fell in love with their sharpness, their wit and their emotional pull. I was intrigued by their depiction of early nineteenth century British society, with its minute distinctions of class and status indicating degrees of good breeding or vulgarity, and I appreciated the way that Austen showed that even her heroes and heroines were flawed, or at least behaved badly on occasion, without sacrificing our sympathy for them. I was also interested in the early nineteenth century in a different way. When I was still in primary school I had become fascinated in the battle of Waterloo and this had broadened to cover all of Napoleon’s campaigns and the nature of Napoleonic warfare.

This interest in military history continued at university and led in turn to a doctorate and then a number of books looking at Britain’s part in the war against Napoleon and Wellington’s campaigns in particular. I edited a collection of confidential letters from Alexander Gordon, one of Wellington’s ADCs, which gave new insight into the way Wellington operated, and I wrote a comprehensive two volume life of Wellington which was published in 2013 and 2015. That book took me fifteen years and by the time I had finished it, I needed a change, but I still loved the period and wanted to keep on writing.

Both Alexander Gordon and Wellington were younger sons whose fathers died when they were very young. Neither inherited enough to live on, and they depended on their elder brothers – who inherited great estates – for assistance in their careers. I was struck by the obvious injustice of this: that one brother would inherit an estate that gave him an income of £16,000 or £17,000 while the other would get only £2,000 of capital (which might produce £100 income), and that everyone accepted that this was perfectly normal and reasonable.

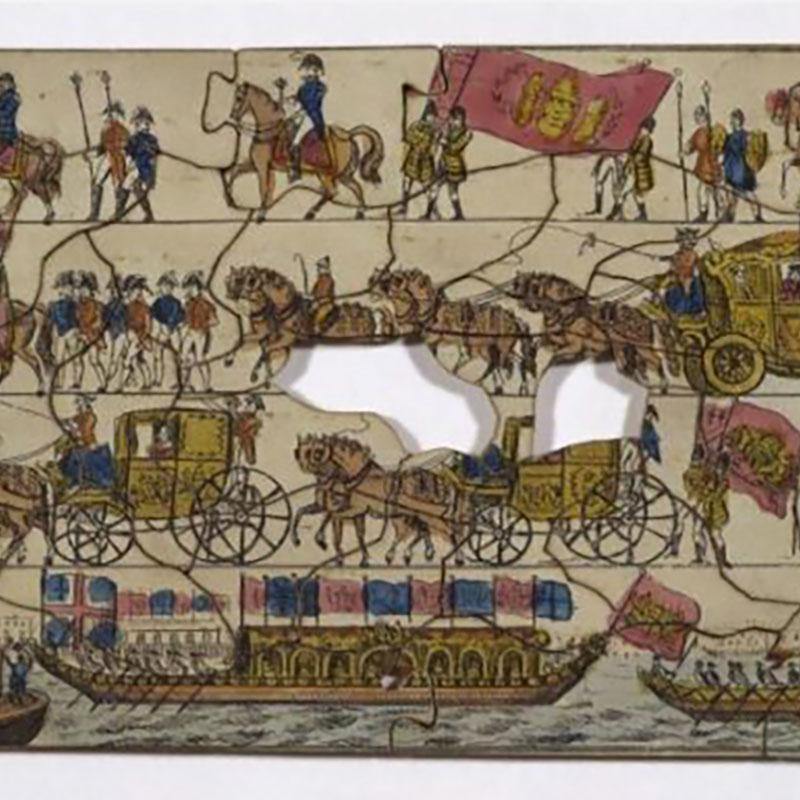

The consequence of this was that younger sons and younger brothers had to go out and make their way in the world even when their father was a wealthy lord. But how could the younger son of a lord, or an independent gentleman, make money in Regency England? Suppose Mr and Mrs Bennet, in Pride and Prejudice, had had five sons, not five daughters, how would the younger ones have made a place for themselves? And for that matter, how did Jane Austen’s own brothers fare? I already knew the rough answer to the question.

That relatively few careers were open to young men of good family without the loss of some social status: they might become officers in the army or the navy; or clergymen; or lawyers. Medicine was rather more dubious, but physicians were often regarded as gentlemen, and surgeon-apothecaries were no longer the crude barber-surgeons of the past. Some young men might follow a family connection into trade (and some business ventures, such as banking, were socially acceptable), while others were sent out to India or other colonies in the hope – a rather desperate one – that they would make a fortune and return a wealthy nabob. But that was no more than an outline, and no one seemed to have gone any further.

What did it mean to become an officer in the army, or a barrister, or a clergyman? What prospects of worldly success or of happiness did these careers offer? What sort of life would they bring? When I dug a little further I found some fine scholarship on individual careers: the clergy and the navy were particularly well covered, while other careers had received much less attention. But even the best of these studies lacked a comparative element. How did a clergyman’s prospects compare to those of a naval officer? Was an attorney, or a curate, or militia officer more suitable as a suitor or a young woman of good family? I set to work to try to answer these questions and I found the result fascinating. The result, Gentlemen of Uncertain Fortune: How Younger Sons made their way in Jane Austen’s England, was great fun to write and I hope will be fun to read, even though some of the lives that it recounts were sad and often quite short.

Jane Austen, her characters and her family figure prominently, for they provide an excellent entry point to the great majority of young men who never became particularly successful. But Wellington is there too, and so is Alexander Gordon; Sydney Smith, the witty clergyman, and a young lawyer, John Scott, whose career almost ended in obscurity but was saved by a chance opportunity. Then there are Henry Thornton, a banker; John Green Cross, a surgeon; Benjamin Smith, an attorney; Henry Roberdeau, an official of the East India Company, and many more. It is a wonderful subject, and I was delighted to find so many vivid first hand accounts describing the lives of these young men, who might easily have provided the model for a character in any of Austen’s novels.

Enjoyed this article? If you don't want to miss a beat when it comes to Jane Austen, make sure you are signed up to the Jane Austen newsletter for exclusive updates and discounts from our Online Gift Shop.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.