The modern idea of Santa Claus in his red suit, delivering gifts via reindeer pulled sleigh was crafted by Clement C. Moore in his 1823 poem,

A Visit from Saint Nicholas. This Santa was based on the Dutch Sinterklaas (Saint Nicholas) and does not, until the mid 1800's cross paths (and merge) with the "olde" English, Father Christmas.

Father Christmas, in fact is the embodiment of the festive holiday season, with no specific religious attachment, though perhaps some slight druid leanings. He does, in fact quite resemble Charles Dickens' Spirit of Christmas Present, also the embodiment of all the good of the season, albeit with a Victorian slant. This spirit, one of four to visit Ebenezer Scrooge in the 1843 novella, A Christmas Carol, is presented to the reader in Stave 3. The Ghost here begins the night quite young and robust and ages throughout the day-- after all, over eighteen hundred of his brothers have walked before him, and this spirit's life lasts but one day:

"The walls and ceiling were so hung with living green, that it looked a perfect grove; from every part of which, bright gleaming berries glistened. The crisp leaves of holly, mistletoe, and ivy reflected back the light, as if so many little mirrors had been scattered there; and such a mighty blaze went roaring up the chimney, as that dull petrifaction of a hearth had never known in Scrooge's time, or Marley's, or for many and many a winter season gone. Heaped up on the floor, to form a kind of throne, were turkeys, geese, game, poultry, brawn, great joints of meat, sucking-pigs, long wreaths of sausages, mince-pies, plum-puddings, barrels of oysters, red-hot chestnuts, cherry-cheeked apples, juicy oranges, luscious pears, immense twelfth-cakes, and seething bowls of punch, that made the chamber dim with their delicious steam. In easy state upon this couch, there sat a jolly Giant, glorious to see:, who bore a glowing torch, in shape not unlike Plenty's horn, and held it up, high up, to shed its light on Scrooge, as he came peeping round the door.

"Come in!" exclaimed the Ghost. "Come in, and know me better, man."

Scrooge entered timidly, and hung his head before this Spirit. He was not the dogged Scrooge he had been; and though the Spirit's eyes were clear and kind, he did not like to meet them.

"I am the Ghost of Christmas Present," said the Spirit. "Look upon me."

Scrooge reverently did so. It was clothed in one simple green robe, or mantle, bordered with white fur. This garment hung so loosely on the figure, that its capacious breast was bare, as if disdaining to be warded or concealed by any artifice. Its feet, observable beneath the ample folds of the garment, were also bare; and on its head it wore no other covering than a holly wreath, set here and there with shining icicles. Its dark brown curls were long and free; free as its genial face, its sparkling eye, its open hand, its cheery voice, its unconstrained demeanour, and its joyful air. Girded round its middle was an antique scabbard; but no sword was in it, and the ancient sheath was eaten up with rust."

In fact, many ancient symbols of the Christmas season can be found in this passage, including the monstrous fire (Germanic Yule Log), holly and ivy decorations (actually Roman traditions) and mistletoe (Druid influence) along with a veritable mountain of food, all of which would have been known and enjoyed during Jane Austen's life time. After all, we think of Dickens as being a Victorian and how the Victorian influence added to our celebration of the season, but the young queen had only reigned for four years when this story was written.

But where, you might ask, did this idea of the Spirit of Christmas in the form of man come from, if not from Saint Nicholas?

According to researchers, "In England the earliest known personification of Christmas does not describe him as old, nor refer to him as 'father'. A carol attributed to Richard Smart, Rector of Plymtree from 1435 to 1477, takes the form of a sung dialogue between a choir and a figure representing Christmas, variously addressed as "Nowell", "Sir Christemas" and "my lord Christemas". He does not distribute presents to children but is associated with adult celebrations. Giving news of Christ's birth, Christmas encourages everyone to drink: "Buvez bien par toute la campagnie,/Make good cheer and be right merry." However, the specific depiction of Christmas as a merry old man emerged in the early 17th century. The rise of puritanism had led to increasing condemnation of the traditions handed down from pre-Reformation times, especially communal feasting and drinking. As debate intensified, those writing in support of the traditional celebrations often personified Christmas as a venerable, kindly old gentleman, given to good cheer but not excess. They referred to this personification as "Christmas", "Old Christmas" or "Father Christmas". At this point the character still belongs to literature and not folk-lore.

Ben Jonson in

Christmas his Masque, dating from December 1616, notes the rising tendency to disparage the traditional forms of celebration. His character 'Christmas' therefore appears in outdated fashions, "attir'd in round Hose, long Stockings, a close Doublet, a high crownd Hat with a Broach, a long thin beard, a Truncheon, little Ruffes, white shoes, his Scarffes, and Garters tyed crosse", and announces "Why Gentlemen, doe you know what you doe? ha! would you ha'kept me out? Christmas, old Christmas?" Later, in a masque by Thomas Nabbes,

The Springs Glorie produced in 1638, "Christmas" appears as "an old reverend gentleman in furred gown and cap".

During the mid-17th century, the debate about the celebration of Christmas became politically charged, with Royalists adopting a pro-Christmas stance and radical puritans striving to ban the festival entirely. Early in 1646 an anonymous satirical author wrote

The Arraignment, Conviction and Imprisoning of Christmas, in which a Royalist lady is frantically searching for Father Christmas: this was followed months later by the Royalist poet John Taylor's

The Complaint of Christmas, in which Father Christmas mournfully visits puritan towns but sees "...no sign or token of any Holy Day". A book dating from the time of the Commonwealth,

The Vindication of CHRISTMAS or, His Twelve Yeares' Observations upon the Times (London, 1652), involved "Old Christmas" advocating a merry, alcoholic Christmas and casting aspersions on the charitable motives of the ruling Puritans. In a similar vein, a humorous pamphlet of 1686 by Josiah King presents Father Christmas as the personification of festive traditions pre-dating the puritan commonwealth. He is described as an elderly gentleman of cheerful appearance, "who when he came look't so smug and pleasant, his cherry cheeks appeared through his thin milk white locks, like (b)lushing Roses vail'd with snow white Tiffany". His character is associated with feasting, hospitality and generosity to the poor rather than the giving of gifts.

This tradition continued into the following centuries, with "Old Father Christmas" being evoked in 1734 in the pamphlet

Round About Our Coal Fire, as "Shewing what Hospitality was in former Times, and how little of it there remains at present", a rebuke to "stingy" gentry.

A writer in "Time's Telescope" (1822) states that in Yorkshire at eight o'clock on Christmas Eve the bells greet "Old Father Christmas" with a merry peal, the children parade the streets with drums, trumpets, bells, (or in their absence, with the poker and shovel, taken from their humble cottage fire), the yule candle is lighted, and; "High on the cheerful fire. Is blazing seen th' enormous Christmas brand." A letter to

The Times in 1825, warning against poultry-dealers dishonestly selling off sub-standard geese at Christmas time, is jokingly signed "Father Christmas".

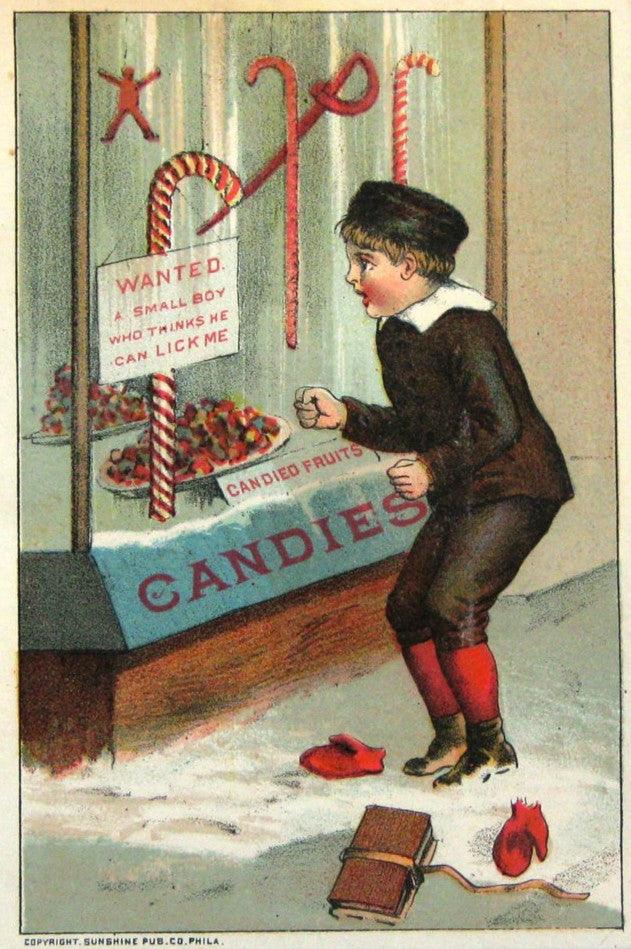

1855 drawing of Father Christmas from

The Family Circle

In these early references, Father Christmas, although invariably an old and cheerful man, is mainly associated with adult feasting and drinking rather than the giving of presents to children. By the 1840s however this had begun to change, and Father Christmas gradually began to merge with the pre-modern gift-giver St Nicholas (Dutch Sinterklaas, hence Santa Claus) and associated folklore. 'Old Father Christmas' appears as a character in two mumming plays recorded in Worcestershire and Hampshire in 1856 and 1860 respectively: he has no specific or consistent dress, but carries holly (Worcestershire) or, in the Hampshire example, a "begging-box" while going on crutches, indicating he is still a reminder of the traditional duty to support the poor at Christmas rather than being himself a bringer of gifts."

Would Jane have been familiar with the idea of Father Christmas? Absolutely. The Austens were a well read, historically acute family. Would they have celebrated any portion of Christmas with a nod towards this character? Personally, I think it unlikely-- Father Christmas did not have an integral part of the holiday as Santa Claus does today-- for the Austens, Christmas (and the following 12 days) would have been first and foremost a religious holiday-- a wonderful time to gather with friends and family, to exchange small tokens of affection, to indulge in dancing, perhaps (never forget that Jane Austen met Tom Lefroy during the Christmas holidays of 1795.) For Regency families, however, Twelfth Night remained, as it had for hundreds of years, the celebration of hilarity and fun, of feasting and dancing, play acting and romancing. It would be another generation or two before it became recognizable as the holiday we would recognize today, complete with tree, stockings, Santa and mountains of gifts.

Laura Boyle runs Austentation: Regency Accessories. Visit her website or her Etsy shop for over a dozen styles of hats and bonnets, as well as numerous other Regency accessories. Follow Austentation on Facebook and be notified of new products as they are added to the inventory.

Historical information on the origins of Father Christmas and images from Wikipedia.com.

The modern idea of Santa Claus in his red suit, delivering gifts via reindeer pulled sleigh was crafted by Clement C. Moore in his 1823 poem, A Visit from Saint Nicholas. This Santa was based on the Dutch Sinterklaas (Saint Nicholas) and does not, until the mid 1800's cross paths (and merge) with the "olde" English, Father Christmas.

Father Christmas, in fact is the embodiment of the festive holiday season, with no specific religious attachment, though perhaps some slight druid leanings. He does, in fact quite resemble Charles Dickens' Spirit of Christmas Present, also the embodiment of all the good of the season, albeit with a Victorian slant. This spirit, one of four to visit Ebenezer Scrooge in the 1843 novella, A Christmas Carol, is presented to the reader in Stave 3. The Ghost here begins the night quite young and robust and ages throughout the day-- after all, over eighteen hundred of his brothers have walked before him, and this spirit's life lasts but one day:

The modern idea of Santa Claus in his red suit, delivering gifts via reindeer pulled sleigh was crafted by Clement C. Moore in his 1823 poem, A Visit from Saint Nicholas. This Santa was based on the Dutch Sinterklaas (Saint Nicholas) and does not, until the mid 1800's cross paths (and merge) with the "olde" English, Father Christmas.

Father Christmas, in fact is the embodiment of the festive holiday season, with no specific religious attachment, though perhaps some slight druid leanings. He does, in fact quite resemble Charles Dickens' Spirit of Christmas Present, also the embodiment of all the good of the season, albeit with a Victorian slant. This spirit, one of four to visit Ebenezer Scrooge in the 1843 novella, A Christmas Carol, is presented to the reader in Stave 3. The Ghost here begins the night quite young and robust and ages throughout the day-- after all, over eighteen hundred of his brothers have walked before him, and this spirit's life lasts but one day:

In fact, many ancient symbols of the Christmas season can be found in this passage, including the monstrous fire (Germanic Yule Log), holly and ivy decorations (actually Roman traditions) and mistletoe (Druid influence) along with a veritable mountain of food, all of which would have been known and enjoyed during Jane Austen's life time. After all, we think of Dickens as being a Victorian and how the Victorian influence added to our celebration of the season, but the young queen had only reigned for four years when this story was written.

But where, you might ask, did this idea of the Spirit of Christmas in the form of man come from, if not from Saint Nicholas?

According to researchers, "In England the earliest known personification of Christmas does not describe him as old, nor refer to him as 'father'. A carol attributed to Richard Smart, Rector of Plymtree from 1435 to 1477, takes the form of a sung dialogue between a choir and a figure representing Christmas, variously addressed as "Nowell", "Sir Christemas" and "my lord Christemas". He does not distribute presents to children but is associated with adult celebrations. Giving news of Christ's birth, Christmas encourages everyone to drink: "Buvez bien par toute la campagnie,/Make good cheer and be right merry." However, the specific depiction of Christmas as a merry old man emerged in the early 17th century. The rise of puritanism had led to increasing condemnation of the traditions handed down from pre-Reformation times, especially communal feasting and drinking. As debate intensified, those writing in support of the traditional celebrations often personified Christmas as a venerable, kindly old gentleman, given to good cheer but not excess. They referred to this personification as "Christmas", "Old Christmas" or "Father Christmas". At this point the character still belongs to literature and not folk-lore.

In fact, many ancient symbols of the Christmas season can be found in this passage, including the monstrous fire (Germanic Yule Log), holly and ivy decorations (actually Roman traditions) and mistletoe (Druid influence) along with a veritable mountain of food, all of which would have been known and enjoyed during Jane Austen's life time. After all, we think of Dickens as being a Victorian and how the Victorian influence added to our celebration of the season, but the young queen had only reigned for four years when this story was written.

But where, you might ask, did this idea of the Spirit of Christmas in the form of man come from, if not from Saint Nicholas?

According to researchers, "In England the earliest known personification of Christmas does not describe him as old, nor refer to him as 'father'. A carol attributed to Richard Smart, Rector of Plymtree from 1435 to 1477, takes the form of a sung dialogue between a choir and a figure representing Christmas, variously addressed as "Nowell", "Sir Christemas" and "my lord Christemas". He does not distribute presents to children but is associated with adult celebrations. Giving news of Christ's birth, Christmas encourages everyone to drink: "Buvez bien par toute la campagnie,/Make good cheer and be right merry." However, the specific depiction of Christmas as a merry old man emerged in the early 17th century. The rise of puritanism had led to increasing condemnation of the traditions handed down from pre-Reformation times, especially communal feasting and drinking. As debate intensified, those writing in support of the traditional celebrations often personified Christmas as a venerable, kindly old gentleman, given to good cheer but not excess. They referred to this personification as "Christmas", "Old Christmas" or "Father Christmas". At this point the character still belongs to literature and not folk-lore.

Ben Jonson in Christmas his Masque, dating from December 1616, notes the rising tendency to disparage the traditional forms of celebration. His character 'Christmas' therefore appears in outdated fashions, "attir'd in round Hose, long Stockings, a close Doublet, a high crownd Hat with a Broach, a long thin beard, a Truncheon, little Ruffes, white shoes, his Scarffes, and Garters tyed crosse", and announces "Why Gentlemen, doe you know what you doe? ha! would you ha'kept me out? Christmas, old Christmas?" Later, in a masque by Thomas Nabbes, The Springs Glorie produced in 1638, "Christmas" appears as "an old reverend gentleman in furred gown and cap".

During the mid-17th century, the debate about the celebration of Christmas became politically charged, with Royalists adopting a pro-Christmas stance and radical puritans striving to ban the festival entirely. Early in 1646 an anonymous satirical author wrote The Arraignment, Conviction and Imprisoning of Christmas, in which a Royalist lady is frantically searching for Father Christmas: this was followed months later by the Royalist poet John Taylor's The Complaint of Christmas, in which Father Christmas mournfully visits puritan towns but sees "...no sign or token of any Holy Day". A book dating from the time of the Commonwealth, The Vindication of CHRISTMAS or, His Twelve Yeares' Observations upon the Times (London, 1652), involved "Old Christmas" advocating a merry, alcoholic Christmas and casting aspersions on the charitable motives of the ruling Puritans. In a similar vein, a humorous pamphlet of 1686 by Josiah King presents Father Christmas as the personification of festive traditions pre-dating the puritan commonwealth. He is described as an elderly gentleman of cheerful appearance, "who when he came look't so smug and pleasant, his cherry cheeks appeared through his thin milk white locks, like (b)lushing Roses vail'd with snow white Tiffany". His character is associated with feasting, hospitality and generosity to the poor rather than the giving of gifts.

This tradition continued into the following centuries, with "Old Father Christmas" being evoked in 1734 in the pamphlet Round About Our Coal Fire, as "Shewing what Hospitality was in former Times, and how little of it there remains at present", a rebuke to "stingy" gentry. A writer in "Time's Telescope" (1822) states that in Yorkshire at eight o'clock on Christmas Eve the bells greet "Old Father Christmas" with a merry peal, the children parade the streets with drums, trumpets, bells, (or in their absence, with the poker and shovel, taken from their humble cottage fire), the yule candle is lighted, and; "High on the cheerful fire. Is blazing seen th' enormous Christmas brand." A letter to The Times in 1825, warning against poultry-dealers dishonestly selling off sub-standard geese at Christmas time, is jokingly signed "Father Christmas".

Ben Jonson in Christmas his Masque, dating from December 1616, notes the rising tendency to disparage the traditional forms of celebration. His character 'Christmas' therefore appears in outdated fashions, "attir'd in round Hose, long Stockings, a close Doublet, a high crownd Hat with a Broach, a long thin beard, a Truncheon, little Ruffes, white shoes, his Scarffes, and Garters tyed crosse", and announces "Why Gentlemen, doe you know what you doe? ha! would you ha'kept me out? Christmas, old Christmas?" Later, in a masque by Thomas Nabbes, The Springs Glorie produced in 1638, "Christmas" appears as "an old reverend gentleman in furred gown and cap".

During the mid-17th century, the debate about the celebration of Christmas became politically charged, with Royalists adopting a pro-Christmas stance and radical puritans striving to ban the festival entirely. Early in 1646 an anonymous satirical author wrote The Arraignment, Conviction and Imprisoning of Christmas, in which a Royalist lady is frantically searching for Father Christmas: this was followed months later by the Royalist poet John Taylor's The Complaint of Christmas, in which Father Christmas mournfully visits puritan towns but sees "...no sign or token of any Holy Day". A book dating from the time of the Commonwealth, The Vindication of CHRISTMAS or, His Twelve Yeares' Observations upon the Times (London, 1652), involved "Old Christmas" advocating a merry, alcoholic Christmas and casting aspersions on the charitable motives of the ruling Puritans. In a similar vein, a humorous pamphlet of 1686 by Josiah King presents Father Christmas as the personification of festive traditions pre-dating the puritan commonwealth. He is described as an elderly gentleman of cheerful appearance, "who when he came look't so smug and pleasant, his cherry cheeks appeared through his thin milk white locks, like (b)lushing Roses vail'd with snow white Tiffany". His character is associated with feasting, hospitality and generosity to the poor rather than the giving of gifts.

This tradition continued into the following centuries, with "Old Father Christmas" being evoked in 1734 in the pamphlet Round About Our Coal Fire, as "Shewing what Hospitality was in former Times, and how little of it there remains at present", a rebuke to "stingy" gentry. A writer in "Time's Telescope" (1822) states that in Yorkshire at eight o'clock on Christmas Eve the bells greet "Old Father Christmas" with a merry peal, the children parade the streets with drums, trumpets, bells, (or in their absence, with the poker and shovel, taken from their humble cottage fire), the yule candle is lighted, and; "High on the cheerful fire. Is blazing seen th' enormous Christmas brand." A letter to The Times in 1825, warning against poultry-dealers dishonestly selling off sub-standard geese at Christmas time, is jokingly signed "Father Christmas".

1855 drawing of Father Christmas from The Family Circle

In these early references, Father Christmas, although invariably an old and cheerful man, is mainly associated with adult feasting and drinking rather than the giving of presents to children. By the 1840s however this had begun to change, and Father Christmas gradually began to merge with the pre-modern gift-giver St Nicholas (Dutch Sinterklaas, hence Santa Claus) and associated folklore. 'Old Father Christmas' appears as a character in two mumming plays recorded in Worcestershire and Hampshire in 1856 and 1860 respectively: he has no specific or consistent dress, but carries holly (Worcestershire) or, in the Hampshire example, a "begging-box" while going on crutches, indicating he is still a reminder of the traditional duty to support the poor at Christmas rather than being himself a bringer of gifts."

Would Jane have been familiar with the idea of Father Christmas? Absolutely. The Austens were a well read, historically acute family. Would they have celebrated any portion of Christmas with a nod towards this character? Personally, I think it unlikely-- Father Christmas did not have an integral part of the holiday as Santa Claus does today-- for the Austens, Christmas (and the following 12 days) would have been first and foremost a religious holiday-- a wonderful time to gather with friends and family, to exchange small tokens of affection, to indulge in dancing, perhaps (never forget that Jane Austen met Tom Lefroy during the Christmas holidays of 1795.) For Regency families, however, Twelfth Night remained, as it had for hundreds of years, the celebration of hilarity and fun, of feasting and dancing, play acting and romancing. It would be another generation or two before it became recognizable as the holiday we would recognize today, complete with tree, stockings, Santa and mountains of gifts.

1855 drawing of Father Christmas from The Family Circle

In these early references, Father Christmas, although invariably an old and cheerful man, is mainly associated with adult feasting and drinking rather than the giving of presents to children. By the 1840s however this had begun to change, and Father Christmas gradually began to merge with the pre-modern gift-giver St Nicholas (Dutch Sinterklaas, hence Santa Claus) and associated folklore. 'Old Father Christmas' appears as a character in two mumming plays recorded in Worcestershire and Hampshire in 1856 and 1860 respectively: he has no specific or consistent dress, but carries holly (Worcestershire) or, in the Hampshire example, a "begging-box" while going on crutches, indicating he is still a reminder of the traditional duty to support the poor at Christmas rather than being himself a bringer of gifts."

Would Jane have been familiar with the idea of Father Christmas? Absolutely. The Austens were a well read, historically acute family. Would they have celebrated any portion of Christmas with a nod towards this character? Personally, I think it unlikely-- Father Christmas did not have an integral part of the holiday as Santa Claus does today-- for the Austens, Christmas (and the following 12 days) would have been first and foremost a religious holiday-- a wonderful time to gather with friends and family, to exchange small tokens of affection, to indulge in dancing, perhaps (never forget that Jane Austen met Tom Lefroy during the Christmas holidays of 1795.) For Regency families, however, Twelfth Night remained, as it had for hundreds of years, the celebration of hilarity and fun, of feasting and dancing, play acting and romancing. It would be another generation or two before it became recognizable as the holiday we would recognize today, complete with tree, stockings, Santa and mountains of gifts.