The Swiss Garden: A Regency Gem

‘…but we shall not have Miss Bigg, she being frisked off like half England, into Switzerland.’ (Jane Austen to Anne Sharpe , 22 May 1817)

Lord Robert Henley Ongley (1803-1877)inherited Old Warden Park in 1814 when he was just eleven years old. During his early twenties, newly in receipt of his fortune, he transformed a 9-acre section of boggy brickfield in north-east Bedfordshire intoan alpine scene such as one would expect to find in the foothills of the Swiss Alps. A great earth-moving feat moulded this level patch of land into an undulating landscape complete with mounds, ponds, serpentine paths and shrubberies, to which Lord Ongley added a Swiss Cottage, an aviary, huge trellis frames arching over sweeping lawns, and a thatched tree seat, complete with sentimental poem etched into a marble slab and the nearby melancholy walk and tiny chapel with its stained glass window. Small but beautifully ornate cast-iron bridges, an Indian Kiosk and a fine Grotto, later incorporated into a Fernery, were added to create a collection of features without which no Regency garden would be complete. At the same time, he remodelled the village of Old Warden, also in the ‘Swiss Picturesque’ style. Local legend has it that Lord Ongley supplied his tenants with red neck-ties, which they were expected to wear as he rode through the village. This was a set piece like no other; a little slice of Switzerland, just under fifty miles north of London!

Lord Robert Henley Ongley (1803-1877)inherited Old Warden Park in 1814 when he was just eleven years old. During his early twenties, newly in receipt of his fortune, he transformed a 9-acre section of boggy brickfield in north-east Bedfordshire intoan alpine scene such as one would expect to find in the foothills of the Swiss Alps. A great earth-moving feat moulded this level patch of land into an undulating landscape complete with mounds, ponds, serpentine paths and shrubberies, to which Lord Ongley added a Swiss Cottage, an aviary, huge trellis frames arching over sweeping lawns, and a thatched tree seat, complete with sentimental poem etched into a marble slab and the nearby melancholy walk and tiny chapel with its stained glass window. Small but beautifully ornate cast-iron bridges, an Indian Kiosk and a fine Grotto, later incorporated into a Fernery, were added to create a collection of features without which no Regency garden would be complete. At the same time, he remodelled the village of Old Warden, also in the ‘Swiss Picturesque’ style. Local legend has it that Lord Ongley supplied his tenants with red neck-ties, which they were expected to wear as he rode through the village. This was a set piece like no other; a little slice of Switzerland, just under fifty miles north of London!

The estate was sold to Joseph Shuttleworth in 1872, who embellished the garden with several impressive Pulhamite stone features, but despite some alterations to the buildings and structures, the garden escaped any significant changes, and the landscape and many of Ongley’s original features survive to this day. A contemporary account of the garden, written by Emily Shore, a visitor to the garden in 1835, described it as:

“A very curious place…full of little hills and mounds, covered with trees, shrubs and flowers. Here and there are arbours shaded by ivy and clematis; in some places are little hollows surrounded by artificial rocks; in others are subterranean paths, besides railing, hedges, ponds, white tents, enclosures for birds, etc. Over the whole are scattered white statues and painted lamps, some on stands, others hanging from lofty arches which join the mounts. The principal object is the Swiss cottage, … which is surmounted by a ‘gilded pill’, on which stands a dove of white stone. What I liked best was the conservatory. We entered a subterraneous passage, at the end of which is a little polygonal chamber, curtained all round with red and white, and carpeted with coloured sheepskin.”[1]

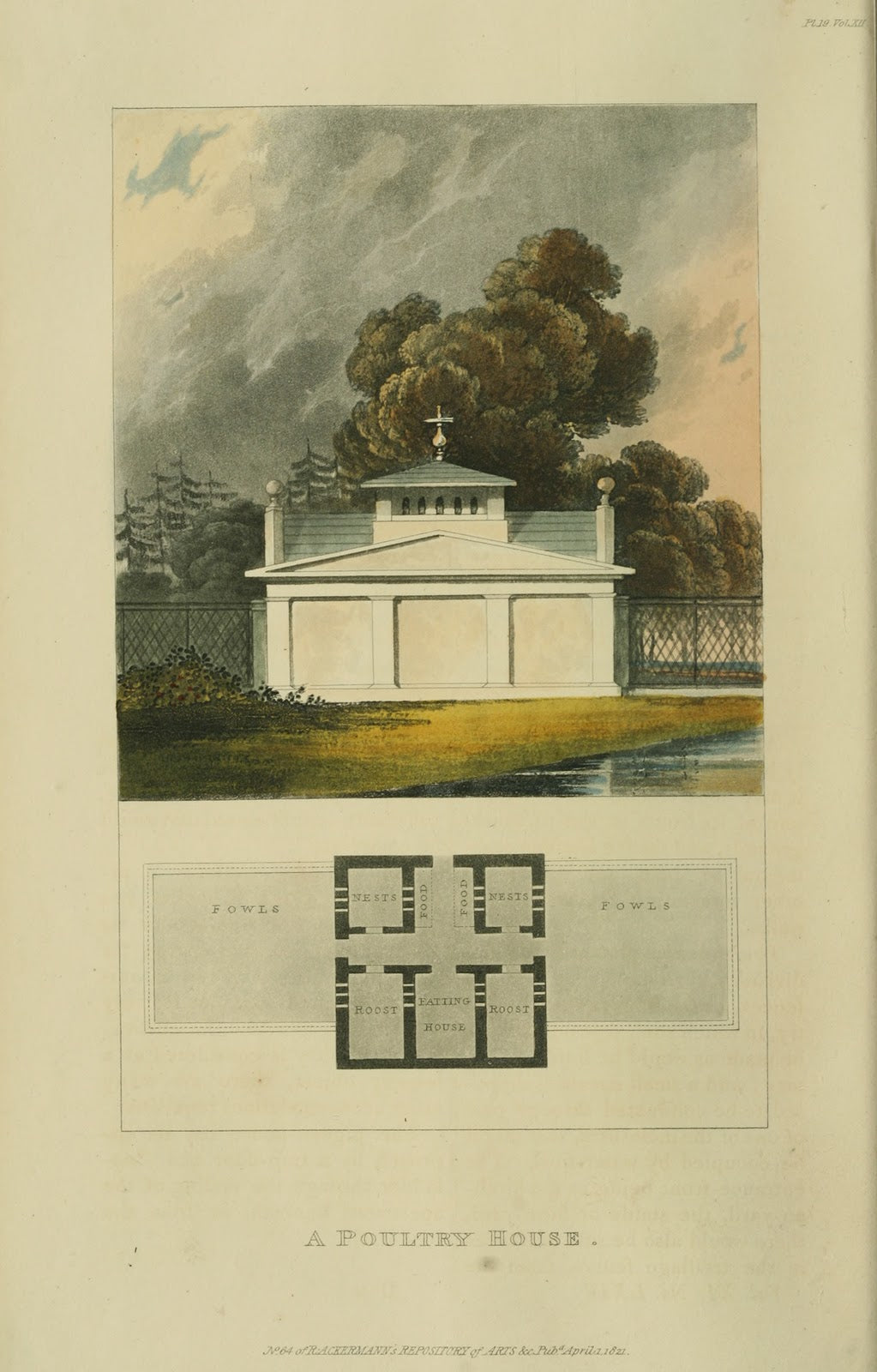

Cecilia Ridley, visiting in 1839, thought the Swiss Garden “the most extraordinary garden in the world made out of a bog; full of little old summer houses on little round hills, china vases, busts, coloured lamps – in short quite a fairyland…”[2] Other gardens of the time were also described as fairylands, notably Whiteknights in Reading, designed by Lord Blandford, later 5th Duke of Marlborough with the help of John Buonarotti Papworth and described in an 1818 book containing over thirty illustrations of the grounds, where ‘…all around is Fairy ground’. Between 1798 and 1819, Whiteknights was the scene of vast extravagance and wild entertainments, all at the Marquis' expense; the splendid gardens, beautifully laid out with the rarest of plants, were its greatest attraction however. Sadly, the Whiteknights landscape has been wholly lost, consumed within the campus at Reading University, but it contained many features which would not have looked out of place in Ongley’s Swiss Garden. Illustrations in Papworth’s Rural Residences of 1832 and Peter Frederick Robinson’s Rural Architecture (1822) and Village Architecture (1833) demonstrate a tendency towards the rustic and the cottage ornée during this period, a trend which had been prevalent since the turn of the nineteenth century. Robert Ferrars, in Jane Austen’s Sense & Sensibility (1811) is:

The estate was sold to Joseph Shuttleworth in 1872, who embellished the garden with several impressive Pulhamite stone features, but despite some alterations to the buildings and structures, the garden escaped any significant changes, and the landscape and many of Ongley’s original features survive to this day. A contemporary account of the garden, written by Emily Shore, a visitor to the garden in 1835, described it as:

“A very curious place…full of little hills and mounds, covered with trees, shrubs and flowers. Here and there are arbours shaded by ivy and clematis; in some places are little hollows surrounded by artificial rocks; in others are subterranean paths, besides railing, hedges, ponds, white tents, enclosures for birds, etc. Over the whole are scattered white statues and painted lamps, some on stands, others hanging from lofty arches which join the mounts. The principal object is the Swiss cottage, … which is surmounted by a ‘gilded pill’, on which stands a dove of white stone. What I liked best was the conservatory. We entered a subterraneous passage, at the end of which is a little polygonal chamber, curtained all round with red and white, and carpeted with coloured sheepskin.”[1]

Cecilia Ridley, visiting in 1839, thought the Swiss Garden “the most extraordinary garden in the world made out of a bog; full of little old summer houses on little round hills, china vases, busts, coloured lamps – in short quite a fairyland…”[2] Other gardens of the time were also described as fairylands, notably Whiteknights in Reading, designed by Lord Blandford, later 5th Duke of Marlborough with the help of John Buonarotti Papworth and described in an 1818 book containing over thirty illustrations of the grounds, where ‘…all around is Fairy ground’. Between 1798 and 1819, Whiteknights was the scene of vast extravagance and wild entertainments, all at the Marquis' expense; the splendid gardens, beautifully laid out with the rarest of plants, were its greatest attraction however. Sadly, the Whiteknights landscape has been wholly lost, consumed within the campus at Reading University, but it contained many features which would not have looked out of place in Ongley’s Swiss Garden. Illustrations in Papworth’s Rural Residences of 1832 and Peter Frederick Robinson’s Rural Architecture (1822) and Village Architecture (1833) demonstrate a tendency towards the rustic and the cottage ornée during this period, a trend which had been prevalent since the turn of the nineteenth century. Robert Ferrars, in Jane Austen’s Sense & Sensibility (1811) is:

'…excessively fond of a cottage; there is always so much comfort, so much elegance about them. And I protest, if I had any money to spare, I should buy a little land and build one myself, within a short distance of London, where I might drive myself down at any time, and collect a few friends about me, and be happy'.Another example of this style of architecture can be found at Blaise Hamlet, near Bristol, designed by John Nash in 1811. This charming hamlet of nine picturesque cottages is laid out around an open, undulating green, and was built to accommodate retired staff from the Blaise Castle estate in Henbury. Like the village of Old Warden, each cottage is unique, and the hamlet was one of the first examples of a planned community – there is a stone sundial and water pump on the green which commemorates its construction. The cottages, again like those in Old Warden, are lived in to this day. This style was later copied widely, helped along by books such as Robinson’s Village Architecture.

So…why Switzerland? The influences for Lord Ongley’s unusual landscape were probably fairly eclectic, and it is also quite probable that he visited Switzerland at some point. Garden historian Mavis Batey, in an article for Country Life magazine in 1977[3], points out that the vogue for Alpine scenery, Swiss cottages and peasant costume that seized England in the 1820s was essentially a by-product of Romanticism. The craving for the sublime and the primitive had made mountain scenery desirable, and a trip to Switzerland became as necessary to the Man of Feeling as the Grand Tour had been to the Man of Taste a century before. The exodus began once peace resumed in Europe following the retreat of Napoleon’s troops in 1815, and two years later, Jane Austen referred to an absent friend as having ‘frisked off like half England, into Switzerland’.[4] The timing also coincided with the publication of the Prisoner of Chillon, offering a new Byronic emphasis to the Tour by showing those who sought to escape the bondage of society’s conventions how to achieve liberation of the spirit through an encounter with the Swiss sublime.

Jane’s interest in garden design, mentioned several times in her novels and the correspondence, starts with William Gilpin and the Picturesque and then moves into an ambivalence about Humphrey Repton, but she does embrace the idea of decorative shrubberies, which feature frequently as the stage on which many of the romantic events in her novels are played out. The key novel for the pre-Swiss Garden period is Mansfield Park, where a discussion takes place about improving one’s landscape, and Repton’s ideas are debated in some detail. Lady Bertram, listening to the proposed improvements, offers her own opinion on the matter: “If I were you, I would have a very pretty shrubbery. One likes to get out into a shrubbery in fine weather.”[5] This, perhaps, can be interpreted as Jane’s personal view being expressed through the debate about Mr Rushworth’s landscape. Although she appears to be criticising Repton in the text, it is very likely that she would have enjoyed walking through the type of flowering shrubberies which he favoured. At Chawton Cottage, where she settled with her mother and sister after the death of her father in Bath, an airy gravel walk was planted up with trees, flowering shrubs and colourful under-planting, a pleasant addition to the productive garden. Scented plants were a vital ingredient, as Jane describes in a letter to Cassandra in 1811:

So…why Switzerland? The influences for Lord Ongley’s unusual landscape were probably fairly eclectic, and it is also quite probable that he visited Switzerland at some point. Garden historian Mavis Batey, in an article for Country Life magazine in 1977[3], points out that the vogue for Alpine scenery, Swiss cottages and peasant costume that seized England in the 1820s was essentially a by-product of Romanticism. The craving for the sublime and the primitive had made mountain scenery desirable, and a trip to Switzerland became as necessary to the Man of Feeling as the Grand Tour had been to the Man of Taste a century before. The exodus began once peace resumed in Europe following the retreat of Napoleon’s troops in 1815, and two years later, Jane Austen referred to an absent friend as having ‘frisked off like half England, into Switzerland’.[4] The timing also coincided with the publication of the Prisoner of Chillon, offering a new Byronic emphasis to the Tour by showing those who sought to escape the bondage of society’s conventions how to achieve liberation of the spirit through an encounter with the Swiss sublime.

Jane’s interest in garden design, mentioned several times in her novels and the correspondence, starts with William Gilpin and the Picturesque and then moves into an ambivalence about Humphrey Repton, but she does embrace the idea of decorative shrubberies, which feature frequently as the stage on which many of the romantic events in her novels are played out. The key novel for the pre-Swiss Garden period is Mansfield Park, where a discussion takes place about improving one’s landscape, and Repton’s ideas are debated in some detail. Lady Bertram, listening to the proposed improvements, offers her own opinion on the matter: “If I were you, I would have a very pretty shrubbery. One likes to get out into a shrubbery in fine weather.”[5] This, perhaps, can be interpreted as Jane’s personal view being expressed through the debate about Mr Rushworth’s landscape. Although she appears to be criticising Repton in the text, it is very likely that she would have enjoyed walking through the type of flowering shrubberies which he favoured. At Chawton Cottage, where she settled with her mother and sister after the death of her father in Bath, an airy gravel walk was planted up with trees, flowering shrubs and colourful under-planting, a pleasant addition to the productive garden. Scented plants were a vital ingredient, as Jane describes in a letter to Cassandra in 1811:

“Our young Piony at the foot of the Fir tree has just blown & looks very handsome; & the whole of the Shrubbery Border will soon be very gay with Pinks & Sweet Williams, in addition to the Columbines already in bloom. The Syringas too are coming out.”[6]

The tiny chapel, reminiscent of the roadside chapels found in Europe, with its stained glass window,

The tiny chapel, reminiscent of the roadside chapels found in Europe, with its stained glass window,Jane, with her rather more refined tastes, may not have been particularly fond of the extravagant excesses of the Swiss Garden described by Emily Shore, but Lord Ongley’s gentle undulations, serpentine paths and tasteful planting are very likely to have delighted her if she had ever seen them. Island beds and shrubberies were popular features of many gardens at the time, as were the Alpine structures seen in the Swiss Garden today. Jane is very likely to have heard of Whiteknights too, and there were plenty of examples to be found of buildings in the rustic style, but what makes the Swiss Garden rather special is that it is believed to be the only surviving example of a ‘complete’ Regency garden, with all its features intact, known in the UK today. Whiteknights, and many other gardens of this period have disappeared altogether, or survive only in part. This makes the recent restoration, funded by a £2.8 million grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund, all the more significant to the current custodians of the garden, the Shuttleworth Trust and Central Bedfordshire Council, particularly as it has been on English Heritage’s Heritage at Risk Register since 2009.

Detail of the North Bridge, designed by Cato & Sons

Detail of the North Bridge, designed by Cato & SonsPreviously hidden behind the hangars of The Shuttleworth Collection aviation museum, the Swiss Garden is now set to take equal billing and prominence as a visitor attraction. The garden’s 13 listed buildings and structures – including six listed at Grade II* – have undergone careful conservation using traditional materials and techniques where possible. Its two-storey centrepiece, the Swiss Cottage, has been re-thatched using water reed from Norfolk, its finials re-gilded with 23 carat gold leaf and missing or broken rustic decoration replaced using slices of Monterey Pine cones and hazel and willow twigs. Almost 4,300 panes of glass in the Grotto and Fernery have been replaced with hand-cut handmade cylinder glass and rosette detailing replaced on the Pond Cascade Bridge. Over 25,600 shrubs and 8,400 bulbs have been planted in 53 beds and 340 metres of path laid using 300 tonnes of gravel. Lost vistas have been reinstated recreating the scenic windows which opened onto very deliberate stage-set views of buildings, bridges, urns, arches and other garden features as originally intended by Lord Ongley.

An ‘augmented reality’ shot depicting the possible design of Lord Ongley’s Aviary – now available on the Swiss Garden’s new (and free) Smartphone app

An ‘augmented reality’ shot depicting the possible design of Lord Ongley’s Aviary – now available on the Swiss Garden’s new (and free) Smartphone app

Corinne Price is the manager of the Swiss Garden, which reopened to the public in July 2014, and is open all year round. The garden has been on English Heritage's 'At Risk' register for some time, and is hugely important in the world of garden history as it's the only completely intact garden of this period in the UK. Please check the Shuttleworth website for current opening times and events, and follow us on Facebook for up-to-date news and seasonal images of the garden.

A Regency Garden Party will take place on Sunday 19th July 2015 to celebrate a year of the garden being open again. Please check the website for details nearer the time. The Swiss Garden, Old Warden Aerodrome, Biggleswade, Bedfordshire SG18 9EP. [1] Journal of Emily Shore, edited by Barbara Timm Gates, 1991, University Press of Virginia, p.113-114 [2] The Life and Letters of Cecilia Ridley 1819-1845, edited by Viscountess Ridley, 1958, Rupert Hart-Davis, London, p.32, 37-8. [3] ‘An English View of Switzerland’, Mavis Batey, Country Life, February 17, 1977 [4] Jane Austen’s Letters, edited by Deirdre Le Faye, 2003, The Folio Society, London, p.341 [5] Mansfield Park, Jane Austen, Collector’s Library Edition (2004), p.73 [6] In the Garden with Jane Austen, Kim Wilson, Frances Lincoln (2008), p.7