Prussian Blue: A Colourful History

Considered the first artificial pigment, Prussian Blue was created at the turn of the eighteenth century, rather ironically by an artist seeking to create a new source for red paint. It rapidly gained popularity as an artist's medium and then later, as a fast dye. It is the traditional 'blue' in blueprints and is used as an antidote for certain kinds of heavy metal poisoning.

Prussian blue was probably synthesised for the first time by the paint maker Diesbach in Berlin around the year 1706. Most historical sources do not cite Diesbach, but Thomas Berger in his 1910 book 'The House of Berger', which documents the history of the Berger family's paint manufactoring business, refers to Johann Jacob Diesbach as creator of the pigment. Prussian blue was named "Preußisch blau" in 1709 by its first trader, which has stuck unto today. The pigment was significant because it replaced the expensive Lapis lazuli based paint used previously and was an important topic in the letters exchanged between Johann Leonhard Frisch and the president of the Royal Academy of Sciences, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. It is first mentioned in a letter written by Frisch to Leibniz, from March 31st 1708 and not before long, Frisch began to promote and sell the pigment across Europe.

As mentioned, the pigment had been termed "Preussisch blau" in 1709, but by November 1709 the German name "Berlinisch Blau" was in circulation, popularised by Frisch. Frisch himself is the author of the first known publication of Prussian blue in the paper Notitia Coerulei Berolinensis nuper inventi in 1710, as can be deduced from his letters. Diesbach had been working for Frisch since about 1701 and in 1724, the recipe was finally published by John Woodward.

The Entombment of Christ, dated 1709 by Pieter van der Werff, is the oldest known painting to use Prussian blue. By 1710, painters at the Prussian court were eagerly using the pigment and not much later, Prussian blue made its way to Paris, where Antoine Watteau and later his successors Nicolas Lancret and Jean-Baptiste Pater used it in their paintings.

This Prussian blue pigment is significant since it was the first stable and relatively lightfast blue pigment to be widely used following the loss of knowledge regarding the synthesis of Egyptian blue. European painters had previously used a number of pigments such as indigo dye, smalt, and Tyrian purple, which tend to fade. Japanese painters and woodblock print artists likewise did not have access to a long-lasting blue pigment until they began to import Prussian blue from Europe.

In 1752, the French chemist Pierre J. Macquer made the important step of showing the Prussian blue could be reduced to a salt of iron and a new acid, which could be used to reconstitute the dye. The new acid, hydrogen cyanide, first isolated from Prussian blue in pure form and characterised about 1783 by the Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele, was eventually given the name Blausäure (literally "Blue acid") because of its derivation from Prussian blue, and in English became known popularly as Prussic acid. Cyanide, a colourless anion that forms in the process of making Prussian Blue, derives its name from the Greek word for dark blue.

Prior to the use of Prussian blue for clothing dye, both indigo and woad were used to achieve a similar shade. Indigo was particularly expensive to import and farmers in England began growing it at home around the mid 1700s. The discovery of Prussian Blue, however, as a synthetic dye, decreased the nation's reliance on imported products. Blue was becoming particularly fashionable and with the many wars being fought by the British navy at the time, manufacturers were hard pressed to keep up.

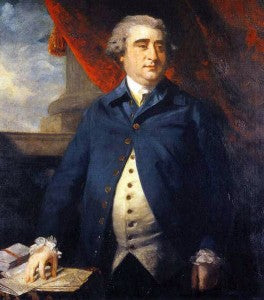

During the American Revolution, the leader of the Whig Party in England, Charles James Fox, wore a blue coat and buff waistcoat and breeches, the colours of the Whig Party and of the uniform of George Washington, whose principles he supported. The men's suit followed the basic form of the military uniforms of the time, particularly the uniforms of the cavalry. In the early 19th century, during the Regency of the future King George IV, the blue suit was revolutionised by a courtier named George Beau Brummel. Brummel created a suit that closely fitted the human form. The new style had a long tail coat cut to fit the body and long tight trousers to replace the knee-length breeches and stockings of the previous century. He used plain colours, such as blue and grey, to concentrate attention on the form of the body, not the clothes. Brummel observed, "If people turn to look at you in the street, you are not well dressed."

This fashion was adopted by the Prince Regent, then by London society and the upper classes. Originally the coat and trousers were different colours, but in the 19th century the suit of a single colour became fashionable and blue found particular favour. The fashion plates from the Continental expatriot, Nicolaus Wilhelm von Heideloff, in Heideloff`s Gallery of Fashion show particular use of the colour, particularly for women and by the early 1800s, it was showing up in other English Fashion plates, for both men and women's wear.

Prussian blue was not confined merely to paintings and fabric dyes, however. It has been discovered in several places, both in the paint and wallpaper of the Prince of Wales's Brighton Pavilion, proving its permanent place in the fashion of the Regency.

Enjoyed this article? If you don't want to miss a beat when it comes to Jane Austen, make sure you are signed up to the Jane Austen newsletter for exclusive updates and discounts from our Online Gift Shop.

3 comments

Thank you! I just learned a lot. :)

James Williamson

The German translation of the Prussian Blue article is terrible. It seems to be machine generated and makes no sense. Also the facts are poor.

Bettina

Thoroughly enjoyed this article about Prussian Blue. I had noticed the color mentioned before in historical novels and of course seen the color in paint supply stores but I never realized what a change the discovery of it made in art and fashion!

Anonymous

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.